Next Time

3 You’re Looking Swell, Dolly

I am Not A Pretty Girl.1 Which is a special challenge, being in the theatre. Also, the parallel of love-bombing and trauma bonding which happens in a situation of gaslighting abuse, with the systems of working in theatre and academia, is discussed. There’s still no Next Time—best to Get Hopeless.

Chapter 3

You’re Looking Swell, Dolly

“What size dress do you wear?”

My high school drama director had a wisp of pure white hair, a low contagious laugh, and a constantly harried demeanor (as can be imagined, being head of theatre for a high school famous for it). She had cornered me in the hall at lunchtime; apparently she’d been looking for me, to ask that question. She was in the middle of casting the vast population of what would be nearly 30 kids in the musical Hello Dolly.

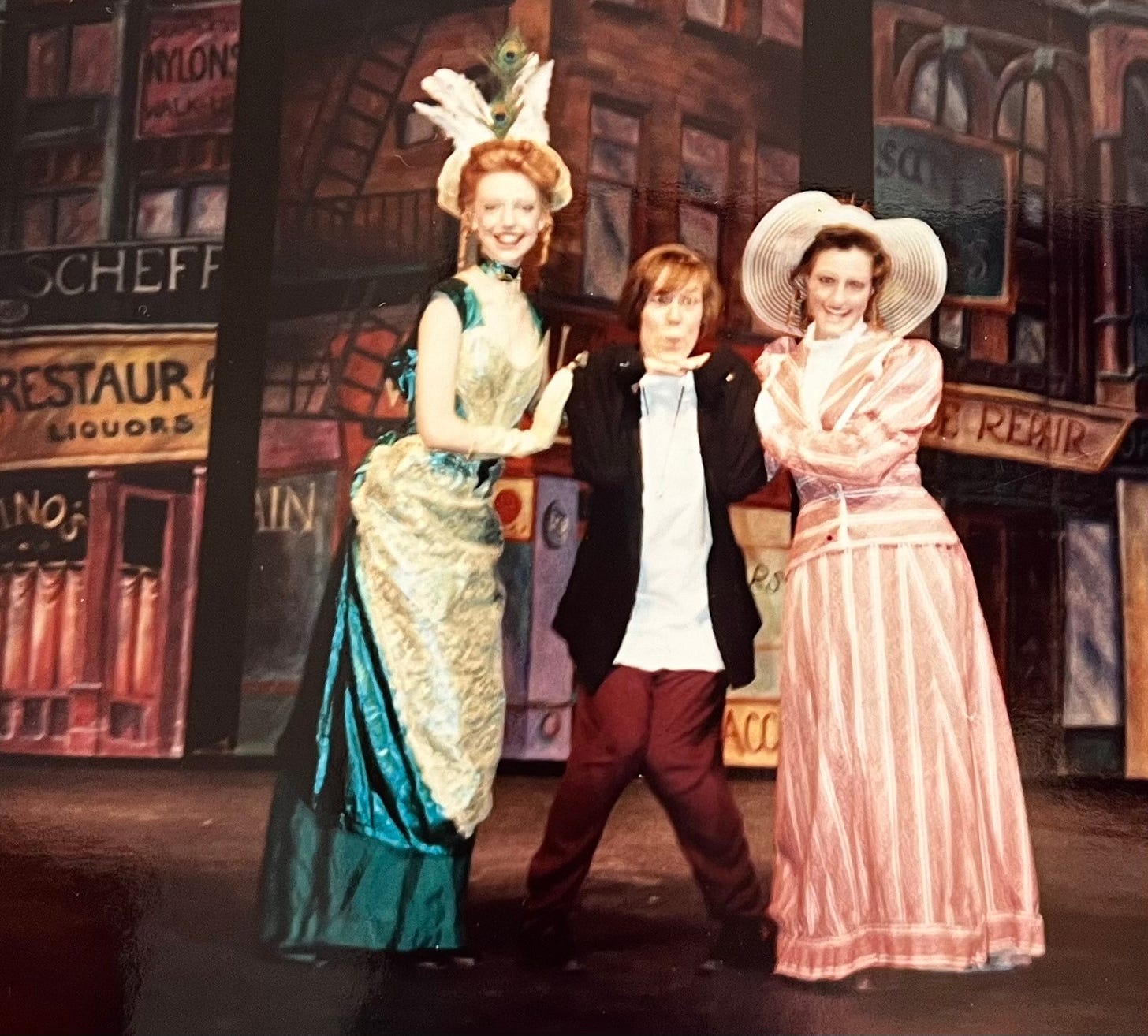

It was the last half of my senior year—I was about to graduate and go up the hill to the renowned CU-Boulder theatre program. As the big Spring musical at Boulder High was always the giant spectacle of not only the school, but often the town itself, and was to be the last show of my glorious high school theatre career, this one was a biggie for me. As a senior, I had been elected along with three of my best friends as a Theatre Guild officer, which meant I had a say in what plays the prestigious school did each year, and was considered a leader and mentor for the younger kids coming in. I was an Honor Thespian, and had wowed audiences a few months ago with my virtuoso portrayal as the title character of The Madwoman of Chaillot.

“I wear a size 12,” I replied. Though an ectomorphic and skinny teenager, I had sprouted to my full adult height. So, thin as I was, without all the curves of mature femininity having popped out yet, I was still indeed wearing a size 12 in especially dresses.

She looked astonished, though, and asked, as though she didn’t quite hear me, “Could you fit into a size 6?”

Nope, nothing doing. Maybe a 10, but not a 6.

Later that day, the cast list came out. Not only did I not get the lead part of Dolly, which would have been assumed, as I was a senior and had an older look and manner appropriate for the part, but I wasn’t on the cast list at all. No role.

In those days, we did junior high, not middle school, and mine was nearly equally well known as the high school in the community for the high quality of its theatre program and its choirs. This isn’t particularly unusual: Boulder schools are all high quality in general because it’s a college town.2 Boulder boasts not only one big-12 university, but a second preeminent private school, known far and wide for especially its Beat poets, its divinity school, and its somatic psychology program. Teachers at the junior- and high schools tend to be those who didn’t get professorships up the Hill at the university, and now, 30 years later, I can more clearly see that their K-12 jobs were in fact better than most would have been at the college level. But I digress…

I was horrifically bullied in 7th grade—I was big, ugly, and poor: the triumvirate of not fitting in. I was very smart, too, and though the popular kids tended to use good grades as extra status points, actually being intelligent didn’t help me at all. In 8th grade, I broke. I changed my look, aggressively, to a personal one, as opposed to attempting to follow a popular trendy fashion I could never keep up with or afford. The difference this made in my mental health is clearly visible in my 8th grade school picture: I’m smiling, I look good, my hair looks great, and I’m comfortable in my albeit acne-riddled skin.

As far as that school’s theatre program goes, I only entered it because I followed my pretty friend in to auditions. As far as I was concerned, I was still a dancer, and it was only because I had aged out of my mom’s dance classes did I wander into theatre. I auditioned for the big Spring musical my first year at that school, and got the understudy for the big lead role. It was Sound of Music, and though I played a mere nun, I did also understudy Maria. 7th graders didn’t have a cast: there was an 8th grade and a 9th grade cast. Such a big role would normally go to at least an 8th grader, even the understudy. But in my audition, I was surprisingly advanced, according to the director, who was also the drama teacher for the school.

Fast forward to 9th grade, junior high graduation year: that school’s biggest theatrical event was also the Spring musical. This year, it was Oliver!, and I was just about to graduate into high school. At that point, I had starred in everything from their Fall plays to conquering a crazy avant-garde one-act that was mostly me monologuing, chosen because the director knew only I could do it. In Oliver!, I was given the role of Fagin, the old man who headed the boy-thieves. Not pretty Nancy, who had a beautiful and sad lament song, and got to wear a dress with a bodice.

That director told me I was the only one in the whole school, of any gender, who could possibly have pulled Fagin off. And he was right. We didn’t have to transcribe hardly any of the music for my female voice—I had a rich contralto, even at 15. We stuck gray facial hair to my young pimply, retainer-clad face, and cloaked my thin teen girl’s body in a big black coat. I already had black boots, breeches, a vest—the assistant director, also a teacher, opened my coat one dress rehearsal and declared, “oh my gosh, this costume is wonderful! Look, you have beautiful breasts and I would never have known!”

My mom still recalls her gasp of awe as I turned around and revealed the character of Fagin for the first time onstage, grasping the young boy’s hand who played Oliver, saying in an accurate theatrical Cockney that I had spent months researching and perfecting, “I ‘ope I shall ‘ave the honor of your hintimate acquaintance…”3

The director was right. I was brilliant. But.

Sometimes a teenaged girl doesn’t need to be interesting and strange yet again—it doesn’t do the things for the developing self esteem that my teachers might have imagined it did. Sometimes a young girl just needs to be…well, a pretty young girl. But if she isn’t, what then?

She gets to be interesting. She gets to be funny, or intelligent, or astonishing. Maybe androgynous—if she’s young enough she’ll be called a tomboy. If older, she’ll be genderqueer, terrifying, dangerous, perhaps bullied for that too. She gets to perform superhuman feats of talent onstage, and be brutalized or ignored offstage. She gets to be admirable, strange, scarily brilliant—and isolated. At that age, a kid needs a tight tribe, she doesn’t need to stand alone, or apart. Larger than life.

But tribes don’t want girls who aren’t small and pretty.

At my high school, the main office for the theatre department was situated just to the right of the big entrance to the school and across the open foyer. It was called the Fishbowl. It’s a big part of that main hallway—it’s a main artery of a hallway that leads pretty much everywhere else in the building, and so the foot traffic past it is always populous and flowing by. BHS is a pretty big school—even at only three grades at the time, just my graduating class was almost 500 people.

It’s called the Fishbowl because it’s a large office, taking up a good portion of the right side of the hallway, and it’s mostly windows: from the ceiling to about a foot or two up from the floor, it’s all glass, crisscrossed with thin metal reinforcement. Even the door’s top half is glass. Though show posters, notifications, and the like are always stuck to the glass, the windows still show pretty much all of what’s going on inside.

That day, I was consulting with the drama director in the Fishbowl, just there behind the cast list taped to the glass, that my name wasn’t on. She was explaining to me why that was, and what her plans were for me during the big, last chance, Spring musical, that I wasn’t performing in. Floods of kids flowed past the clear Fishbowl as we talked, theatre kids included, and I wondered what they thought—there I was, in intense conversation with the director, sitting just behind the cast list for the last play in my last year at the school, my star name conspicuously not on it. What were they thinking, what sorts of gossip was happening along that aquarium-like hallway?

The director explained that she wanted me to be her assistant director for Hello, Dolly—I would have been great as the lead, she said, but so would my friend, and my friend could never do what she needed me to do, as assistant director. In this important role that wasn’t a role, my responsibilities would include: helping with acting coaching, taking notes during rehearsals, giving said notes aloud to the cast at the end of each rehearsal, and in general keeping everything organized. I’d also be given one whole musical number to choreograph myself. A big job for a teenager.

She made sure I knew that I was getting this important position for my senior year musical, because of how mature, brilliant, and competent I was—no one else had the talent or the wherewithal, she said, to do this. She knew she could rely on me as a real assistant director, not just a kid.

Oh, and also.

Another reason—they had rented a size 6 dress for Dolly’s main costume, from a local professional company. They’d already paid for it, so…

“Oh wow! You are striking! You could be a professional model!”

The woman, petite and black-bobbed and very stylish herself, was a professional makeup artist, and was helping out as a guest artist the year before– this was my 10th grade year in high school, and that year’s musical was Peter Pan. She had also been teaching some guest lecture type makeup workshops for some of the drama classes. She was the real deal—she’d worked on Broadway, and also for some of the bigger fashion mags on their models.

I looked around, realized she was addressing me, stupidly asked, “Uh, me?”

“Yes! Wow, you’re so tall and you have such beautiful cheekbones. You could be a model!”

“Really?”

“Sure! All you’d need to do is lose about 20 pounds.”

My jaw dropped.

I was in 10th grade—I was 16 years old. While this meant I was gloriously gothy, style wise, and at my full adult height, I was not yet decked out with the womanly curves that would later come with maturity. Numbers? Besides the size 12 dress? I was 5’9” in height, and weighed 120 pounds. Teachers had actually consulted my parents, concerned at my thinness, asking if I ate enough. I did, I ate just fine. I was just a teenager.

I stood there for what felt like a long time, trying to figure out what 5’9” and 100 pounds would look or feel like. Or how I would possibly do such a thing. I laughed, and shook my punk head at her. She wasn’t joking, though.

“Uh, thanks but no thanks,” I said, incredulous.

“Let me know if you change your mind.”

Even at 16, I was astonished—how is that level of emaciation at all okay, let alone a model, a standard of beauty?! I had no wish to starve, nor render myself invisible. I was young enough that I still was of the mind that the world needed to get out of my way, not that I needed to diminish myself for it. And I had heard the horrific stories of what happens to your health when you suffer from anorexia.

I did regularly buy magazines like Vogue, Elle, and the like because I was interested in fashion. I was ostensibly and overtly repulsed by the late-‘80s fashion of stick-thin models as the beauty norm, while at the same time, as I mocked the unreality and poor health of those human coat hangers with the conscious forefront of my mind, the repetition of that image of beauty shoved down my throat since childhood along with the reverberations of childhood bullying meant I was more affected by my own falling short of that ridiculous standard than I realized.

My outraged anger and mocking disbelief at that makeup artist was a good start in adult self-confidence, but my own distaste for and even hatred of my body was already deeply seeded in my psyche. My pride in my size and my own personal beauty was tenuous at best, a fake demeanor put on for potential bullies at worst. Having two beautiful, tiny best friends didn’t help.4

Now, I am fully aware that doing the assistant-directorship position for Dolly, and playing Fagin before that, were much better learning experiences for me and a better use of my peculiar talents than playing either female lead would have been.

In Dolly, I got to compose my first dance choreography and was in charge of being basically an acting teacher and director for the whole cast, as I was the one to give notes after each rehearsal. And I was great at it. But for an 18 year old kid to be literally left backstage because she’s not small and pretty enough? It was the cap to a long young life of being bullied and othered—not good enough disguised as more brilliant than anyone. Admired, not loved. Alienated for being extraordinary. If you’re interesting or impressive, but not pretty, you’ll be abstractly admired, from afar. If you’re lucky. But people don’t want to be even just friends with a girl who isn’t pretty.

It’s a messed up paradox that has repeated itself in my life again and again. It hurts. You’d think it wouldn’t hurt anymore, but it does. I was a tough cookie already at 18 by the time Dolly came around, but this kind of life leaves one raw, and unable to function socially in a healthy way. I learned as I grew up and of age to take the stage as a coping mechanism, in any number of circumstances. Which is fine and all, but it doesn’t lend itself to learning about intimacy. It gives one a well-made set of super-shiny armor, that reflects everyone around it back to them. It’s beautiful. And people love looking at themselves in it. But it’s still armor, and it has been extremely difficult for me to take the riveter to that armor now later in life when I need to.

And it’s easy to see how this pattern of othering in my early life would leave me susceptible in my late twenties, with barely two men having notched my bedpost, to easily succumb to a narcissist’s silver tongue.

I already knew I was smart, intelligent, accomplished. Interesting.

All he needed to do was tell me I was pretty.

Since high school and through college, I’ve been typecast and not cast over and over again—it’s part of the world of a large, not-so-pretty woman trying to be a performer. It got to the point where I stopped auditioning for things altogether, and only took fight directing jobs, as the pay-to-time ratio was a lot better, and hey—I still got to put my art on stage, even if it wasn’t me actually doing it...

I didn’t go back to performing regularly until my 40s, when I discovered and entered the big burlesque boom—a much more body positive field than acting ever was, and far less misogynist than the stage combat field still is. You’d think, in an art that works so much around actors’ egos, that self-advocacy would be encouraged, but in fact it’s the opposite. If an actor speaks up or, gods forfend, complains about bad treatment, she’ll be labeled arrogant, vain, hard to work with, and even blacklisted.

So as a woman in theatre, especially when young and “paying dues” in small and/or community organizations, we’ll take all kinds of abuse, from overworking to sexual harassment, just to not rock the boat. Actors are taught to do this by the narcissistic system—the idea is that putting up with abuse with a smile on your face will open up more possibilities for more and better roles at more and better places that might pay more and better. If you’re lucky. If you keep smiling.

Actors Equity is a union that is supposed to do something about the especially overtime underpaid type of unreasonable demands of acting gigs. It’s a setup that guarantees decent pay, reasonable hours and breaks, and insurance. How it works is:5 An actor does enough performances, getting points for each, then gets her Equity card once she earns enough points.

Here’s the kicker, though: once an actor is Union, she’s not allowed to take any jobs (paid or no) that aren’t specifically Union. And there’s the rub: earning an AEA membership can easily be a sure way to consistent unemployment; it’s rare that a theatre company will have enough money and resources to provide the Equity requirements, and those few that do often only have them available for a couple of the bigger roles. These, of course, are viciously competed for. Let alone the awkwardness of a select few actors being well taken care of, with the rest of the grunts sweating for pennies.

Or what’ll end up happening is: Equity actors will cheat and take non-Equity roles, which ups the competition even for those parts, as well as basically renders the potential good thing of the Equity laws useless. Add to this all the factors about being female, big, difficult to cast, etc. and AEA tends to be career suicide indeed. The mythical Next Time is especially insidious here—earn your card and then it’ll be glorious! Still not getting cast? Well maybe you need to take this audition course for $500. Still no? Maybe you need to move to a city other than Denver. What’s that? This actor friend of yours pretended to not have an Equity card so she could get cast in that part you were up for? Well maybe you should do that next time. Maybe you just need to look more like what casting directors are seeking. Lose a little weight. About 20 pounds should do it.

We’re taught as young performers that we’re supposed to get experience, and exposure, by saying yes to everything—and, more importantly, no to nothing. That way, we have a robust resume when we... when we what?

Well, the myth is that when The Big Break comes along, we’ve got a good body of work to show. Reality is, though, there ain’t no big break, and the very few exceptions only serve to prove that rule. And so there we stay, compromising our healthy boundaries and swallowing our personal consent, while years go by and we, starving, in psychological tatters, still strive for the mirage of Next Time.

There’s a concept in Necessary Endings by Henry Cloud, which he calls “The big change motivator: Get Hopeless.”6 This is related to Cruel Optimism: if we are victims of gaslighting with all that warped, inaccurate sense of what’s actually going on, hope makes us keep on keeping on, “going down a road that has no realistic chance of being the right road or making what we want come to pass.”7 In other words: hope keeps us going. Which can be a big problem, especially if we’re not seeing reality clearly.

The term “gaslighting,” meaning a particular kind of manipulative abuse, comes from the movie of nearly that name, where an abuser traps his wife in the basement and keeps turning down the lights, all the while telling his victim she’s crazy for noticing the oncoming darkness. Cloud’s “Get Hopeless” advice is about turning the lights back on for ourselves, all the way up, so that we can clearly see the whole picture of our real situation, clearly point out the abuse for what it is, and hopefully get out.

Narcissists in charge of us will set so many traps in place that we’ll feel it’s impossible to escape, or, as was the case with my marriage, that we aren’t being abused, that it’s our own fault if we’re miserable. Adding financial abuse to the litany of gaslighting manipulation can be a trap too, making it literally as well as psychologically impossible to break free. I happened to get a windfall which broke the financially abusive chains from my husband, but I have yet to be able to shed all my adjunct jobs. As little money as I make there, I do still need it, and with my long academic career, I’m not qualified to do anything else. Waiting tables or bartending? I have no experience, plus those jobs are very sought after and competitive where I live—I doubt I’d get hired in that capacity. Corporate work, where they actually pay well? I’m a 50 year old woman—who’s going to hire me for any entry level position, also with no business experience or education in that field?

Go back to school? Don’t make me laugh...

Theatre, especially for performers, is abusive in the exact same way as the narcissist partner and the exploitative job: asking everything from us, giving nothing back but abuse. And replacing us immediately if we notice or complain.

An adjunct does the exact same thing that a put-upon actor will: endure horrific working conditions and abuse because they need the job. They’ll pay for extensive professional training even though they’ve already got a heinously expensive PhD which will keep them in oppressive debt for the rest of their lives. And they learn quickly to not speak up, so as not to lose the small thing they have. Like the actor, the adjunct will also fall prey to the dangling carrot of the promised next great opportunity or promotion possibility.

It’s the same idea as the “paying your dues” of the up and coming actor, eternally up and coming, never hitting the big time: sure, adjuncting means you make less than a living wage, with no insurance or even basic benefits like an office for office hours, and no job security. But this is just what you need to do while you work your way up the ladder into tenure.

This is what I thought, naively, when I graduated with my MFA and a mountain of debt, back at the turn of the millennium, and started my first adjunct jobs. Now, 20 years later, I know perfectly well that there’s no chance for me to get a tenured position, ever. Nor is there, even after that long a seniority, any vestige of job security, or any raises to speak of. And I’ll never be able to pay back my student loans, which continue to increase the longer I’m unable to pay them.8

Academic jobs are a trap, similar to acting ones--it takes some very high level, specific, and expensive credentials even to get an adjunct position, and for what? A lifetime of poverty? An addiction to the false promises of Next Time? Dependence on the financial abuse of a system that doesn’t give two figs for my wellbeing?

If you can sit down, look reality in the face, not the fake promise of a Next Time that a narcissist will offer, and Get Hopeless? Your chances of escaping the abuse will rise exponentially. But it’s hard—those jobs don’t make it easy to give up the idea of Next Time, in fact they insist upon it. An adjunct will, as will an actor, end up in a trauma bonding situation, like Arabi talks about in Power, relying on the relationship with the abuser even as the conditions worsen, and as each promise for a better future is broken, again and again, they stay. And if they dare to try and salvage a little dignity, they’ll be punished, ousted, or blacklisted for their pains. It ends up being easier, almost less painful, to put up with the abuse. To bear those ills we have, rather than fly to others we know not of.

In theatre, as in adjuncting, if you self-advocate or stand up for yourself, you’re a troublemaker. There’s hundreds of prettier people out there with the same or better credentials that will flood in to replace you, smiling, wielding PhDs and Actor’s Equity cards and legacy wealth. And they’re a size 0.

They’ll take the role, and be thankful for it. What’s your problem? You must be difficult to work with. Good luck getting hired again...

Late in the rehearsal process for Hello Dolly, our director came to me in a panic, asking if I could please do a special coaching session with the lead actress, my pretty friend in the pretty dress who was playing Dolly. Her performance was falling short, our teacher lamented—the girl was too mild, bland, sweet, young, and frankly boring onstage. Her songs sounded technically fine, but she wasn’t embodying the brash, boisterous, middle-aged busybody that Dolly needs to be.

“Could you just...give her some of your oomph?” the director pleaded.

“I can try, but, listen.” I replied, “if you wanted oomph, you should have cast me. You cast a size 6 dress instead. And it looks beautiful up there. But that’s what you wanted, and that’s what you got.”

One early moment of self-advocacy. Wow. And yes, I did say that to my teacher. I don’t honestly remember how she reacted, either—I vaguely recall her just setting up the coaching session for me as though I never admonished her. No idea if she heard it or learned anything from it.

If only I could have kept that self advocacy up into my 20s, maybe I wouldn’t have gotten married. But narcissistic abuse is subtle—it alternately wears you down and glorifies you till you don’t know which way is up. That’s how they get you. That’s how they keep you.

Inspired, not by Ani diFranco, but this article by Julia Doolittle: ’Not a Pretty Girl.’

Both the junior high and high school I attended had been touted in the town and in the local theatre network (let alone amongst the college recruiters) as putting on the sort of productions you’d forget were done by kids. Fiddler on the Roof at BHS prompted an op-ed raving about this fact; a woman had gone to the show begrudgingly, having promised one of the young actors, wondering why she put herself through this torture, only to frequently forget she wasn’t watching professionals.

I remember this as Fagin’s first line in the musical. No idea what page number in the script it was, but Lionel Bart is the playwright and lyricist.

Fun fact: my beautiful and very thin best friend played both Nancy in junior high, and Dolly in high school. So she got the pretty parts, I got the interesting ones (when I got them at all), in direct competition with her. She’s good, don’t get me wrong. But it’s not about that.

This is how it worked as of this writing—there was a big shift that happened around the #metoo and #iseeyouwhitetheatre movements, and my understanding is that much of the merit based restrictions of AEA have been changed, if not lifted altogether. Which of course also begs the question of its worth at all at this point. All of which makes it easy to see what a mess the whole thing is now.

Cloud, Henry. Necessary Endings. HarperCollins Books, 2010 (p.84).

Ibid., p.85

The student loan situation I describe above was true as of that writing. But, a couple years after I wrote this lament, I was astonished and grateful to have been on the list of initial recipients of the student loan forgiveness program installed by the Biden administration. I was one of that first group to receive it, who woke up one morning to see my balance (of over $100,000) had been magically eradicated. While this doesn’t solve all my financial problems, boy does it sure help.

Another great chapter, Jenn. One thing I thought about reading this is that acting and teaching both provide an opportunity to perform - seductive and addictive in its own way. It’s the kind of hook that keeps you (or me) in. I also like the idea of hopelessness sometimes being clarifying.

I have a minor suggestion re: how to handle timing with the student loan reference - DM me if you’re up for that :-)