Next Time

III (Appendix) Writing My Way Up & Out

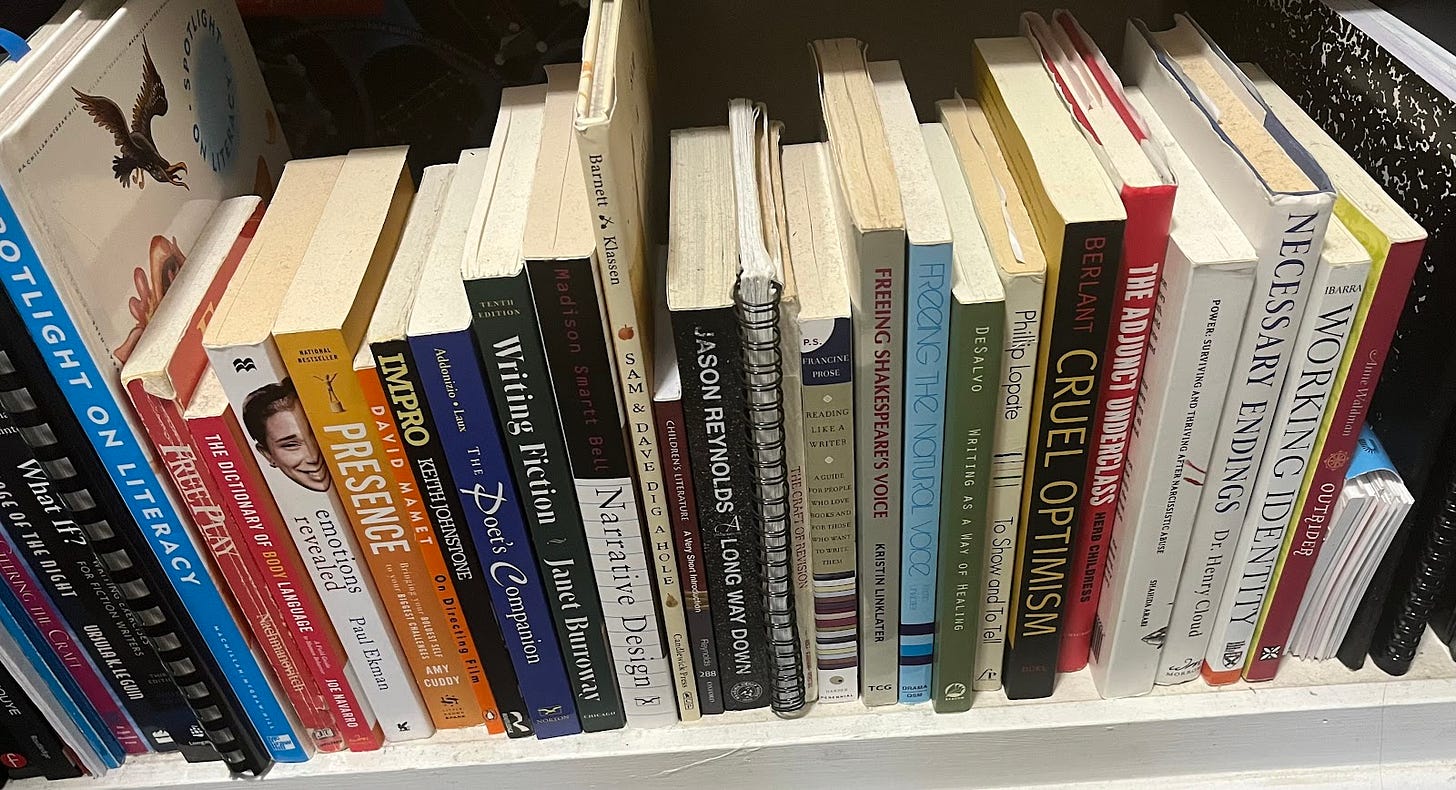

In which I share with my readers a sort of lit review. Here’s the work I looked at for this memoir’s process, and why. Here are my inspirations and aspirations, and those near where this book will be shelved.

NOTE: This last installment of Next Time (Saturday Morning Serial) will be a bit too long to read inside your email inbox, so trip on over to my Substack to get the whole enchilada.

Thank you for joining me on this memoir journey. Enjoy the Appendix.

Appendix

Writing My Way Up and Out

When I decided to create a lit review of sorts for this project, I discovered quite a bit about my own writing, my own process, and felt pretty cool about where I could envision my book being shelved in actual bookstores. In the process of this exercise, I found that there are a lot of memoirs out there, and a lot of self-help books; many personal essays, and lots of excellent research writing. And of course there exist purely scientific non-fiction books that analyze the social topics and psychological traumas I touch on. Very few if any do all of these things at once, though, and those that do, tend to slant much more on the analysis/research side, with only a tiny bit of the personal factor.

I wanted to share this reading list with you, to enrich your future reading explorations, foster more discoveries on how you can write Up and Out of your own life experience, and hey, maybe these will inspire you to tell your own story. Also, I personally enjoy seeing a little bit of authors’ behind the scenes stuff and inspirations and influences, so I thought I’d give you a little backstage tour, in case you do too.

I’ve divided these resources into the following four categories: Self-Help (self-explanatory); How-To (resources about how to write memoir and personal essay); Memoir & Personal Essay (model exemplars of the genre); Works Cited (literally just things I quote from); and Other (those that defy relevant categories but that were inspirations to me nonetheless).

SELF-HELP

I’m not sure what it says about life in the business world that there are so many self help books geared for people in that particular career sector, and maybe I shouldn’t speculate too much. The self help books I used most for this project were actually largely curated for me by my partner, who has been valiantly supporting me in my agonizing attempts at extricating myself from academia and into a new living. But then I started writing this book and I found each of them to have particular uses for different parts of my story, and it’s been great delving further and differently into them as I go. I guess, when you’re writing about yourself, it makes sense that books about self-introspection and self-help would be good sources for that process.

~

Arabi, Shahida. Power. Thought Catalog Books, 2017.

This is a psychological self help book focusing on the experience of, and recovery from, gaslighting abuse from a malignant narcissist. Arabi goes into detail on what makes a narcissist, what the various stages of abuse from one tend to be (love bombing, triangulation, hoovering, etc.), and what the best practices are for dealing with the traumatic aftereffects of such an experience. Less a coherent whole than a collection of both her more well known articles on narcissistic abuse and newer thought pieces on same, this is the kind of self-help book you can randomly flip through and find any number of powerful guidelines. Her tone is never exactly personal, but she gets to sounding angry enough in places that one gets the idea she’s reacting to her own experience by composing this helpful manual. I quote from this book in a few of my chapters.

Cloud, Henry. Necessary Endings. HarperCollins Books, 2010.

This is a self help book for the business world, centered on when and how to leave a bad situation. How to recognize it, how to deal with it emotionally, and how to do it. Cloud talks mainly about leaving professional situations, but also briefly refers to personal relationships. As a psychologist and corporate coach, he advocates getting ”realistic, hopeless, and motivated”1 in order to save your career and your mental health. I quote from this book in a couple places, but mainly later in my piece I go into his concept of Getting Hopeless as a cousin to the escape from Cruel Optimism that comes from Berlant.

I’ve been working a lot on my own past role as doormat, and I’ve found that a healthy, cleansing, and selective hatred has been incredibly empowering, as has an eschewing of the magical thinking of enforced, toxic positivity. Cloud’s “Get Hopeless” pep talk was revelatory in shaking off the stagnation of my life. It’s a practice in taking my own power, to ask myself Cloud’s question: “What reason, other than the fact that I want this to work, do I have for believing that tomorrow is going to be different from today?” What an excellent question to ask myself about both my marriage and my job.

Ibarra, Herminia. Working Identity. Harvard Business School Press, 2004.

This is another self-help book for the business sector. It focuses on the phenomenon of the middle aged person faced with a huge career change, describes why it happens, how it feels, and perhaps most importantly, how to navigate and achieve such a thing. There’s no memoir involved, but Ibarra does use several biographical case studies to illustrate the various stages in said transition process, which helps to put a human face to the theoretical. I first got this book to help me along with a hopeful career change out of academics before the pandemic made such a thing impossible, and now I’m finding it useful in especially her discussion of how, by the time we’re 50, our job has become our identity in a lot of ways, and how understandably painful that is to change if and when it’s necessary.

The case study that hit home the most for me in this book was the one about the middle aged female academic. Though she had other things going on in her life that were slightly different than mine, it was still representative of my situation and her painful career transition process resonated deeply with me. Her story and the book as a whole, too, lifted me out of despair: its central message is: Yes it’s really hard, it’s not just you, and you’re not alone in your struggle.

Malesic, Jonathan. The End of Burnout. University of California Press, 2022.

It seems like a given that burnout is a normal thing for the business world, but coming to the fore of the news these days, is the level of burnout that all teachers suffer. This news isn’t new, though the studies of burnout have long been mostly focused on the corporate world instead. It seems as though, since the pandemic, the very sorry plight of teachers everywhere is suddenly a hot button issue. A teacher shortage? Try: a shortage of professionals with advanced degrees not taking abuse anymore.

Malesic’s book, like so many others on this topic, traces the beginnings of burnout, describes what it feels like, summarizes why it’s a problem across workplaces, and even suggests a solution or two. The difference is, Malesic doesn’t chronicle his leaving of a high powered corporate job, he’s describing how his tenured professorship almost literally killed him, and where and how he moved on. I was struck by this—I mean, a tenure-track position has long been the carrot on the end of my career stick, a promise of something better and an escape from the abusive adjunct grind. I even made the moves, almost to acceptance, of a PhD in Theatre, just to give myself that extra edge, or so I thought. But hearing about Malesic’s agonizing journey through burnout through this study was enlightening. It even made me feel loads better about having given up on the PhD. I’m, oddly enough, the better for it.

What’s the difference, though, between burnout and just being oppressed by a shit job? Is there one? Does it matter?

HOW-TO

Similar to the self-help books, I had these writing textbooks before I ever started this project, for totally different reasons. In this case, they’re from courses I teach at DU for their master’s degree in Professional Writing. The three courses most useful in their materials for my process in writing this book (including required textbooks) were: Writing and Healing, Fiction Fundamentals, and the Creative Nonfiction unit in a cross-genre writing class. Especially Writing and Healing—that class spanned genre and centered around writing about yourself, your life stories, and writing through and about trauma. I didn’t have a lot of experience with this kind of writing (beyond journaling and blogging) before teaching that course, and I learned so much from these textbooks. I’ve continued to revisit both Lopate’s and DeSalvo’s guides, especially, throughout this whole process.

~

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction (10th ed). U. of Chicago Press, 2019.

This is a book I’ve required for several writing courses at DU’s Professional Writing Program, and it really is an essential guide for anyone wanting to write better stuff, fiction or no. Though my book is obviously not fiction, I found certain sections of this writer’s guide to be super helpful, particularly in the structuring of the whole piece. Burroway’s discussion of Freytag’s Pyramid and how the inverted check mark shape is actually a more effective story structure was something I actively and directly used in several of my own chapters. After all, even though I’m not telling fictional stories, they’re still stories, right? And as such, techniques for good story writing are valid for this work, too.

DeSalvo, Louise. Writing as a Way of Healing. Beacon Press, 1999.

This is a required textbook for a class I’ve taught a few times at DU, called Writing and Healing. It’s a step by step guide through the process of writing memoir, with a big dash of poetry therapy thrown in for good measure. DeSalvo goes through various ways of writing various types of trauma, and has a fantastic setup of each phase of writing memoir (especially memoir about traumatic experiences), and her description of what should go into each progressive draft has been very helpful for my process. I was teaching this course right when I began this project and so using this book has been a natural thing to do.

Especially the section on how to expand your memoir after having generated a first draft, has been essential to my revision process. Since all this stuff actually happened to me, it’s hard to know what details I need to add; what does a reader want to know more about? I would have no idea how to expand half these stories without this book’s guide (as well as the essential help of my writing coach). DeSalvo gives a list of 12 draft-deepening questions in her Stages of Growth II chapter on which I’ve put a permanent bookmark. They’re questions a memoirist can ask herself in order to enrich the retelling of a life event she experienced, but a reader hasn’t.

Lopate, Philip. To Show and to Tell. Free Press, 2013.

This is a source I quote from in Chapter 1. The book is one I’ve required for DU courses in which I teach personal essay writing—and it definitely is more focused on personal essay than memoir. Lopate’s book is a great source in that he goes over that magic balance of showing vs. telling in memoir and personal essay. Subtopics I found useful here are: how to incorporate research, how to write yourself as a character (both as narrator and protagonist in a story), and his analyses of some literary personal essays are excellent reads, as well.

Lopate’s concept of a memoir writer needing a “tone of authority” was so inspiring to me that it ended up being the main theme of my introduction chapter, where I discuss how hard this project was to begin. It was empowering during the worst of my writer’s block moments: “I do not want to imply that narrative conviction is nothing more than a technique. However, I do think that what the professional knows is that there are days when the mental cupboard is rather bare, but you can still get by with a tone of assertion.”2

MEMOIR/PERSONAL ESSAY

I was never a big writer of nonfiction until I started blogging a lot, and even then I still considered myself more of a poet or a Fantasy writer, until I began the Problematic Tropes series of articles.3 Personal essay and memoir were also not my first choice of pleasure reading, that is until I started working on this book. That has changed—the number of amazingly composed, beautifully written works that I’ve discovered and that have been shared with me since then, to help and inspire my writerly generative flow, still surprises me. The following are some of the best written and/or most relevant topics to my piece.

~

Anonymous. “Academe, Hear Me. I Am Crying Uncle.” Inside Higher Ed, April 2022. Available: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2022/04/22/burned-out-professor-declares-academic-chapter-11-opinion

Poor Anonymous. I hear them, and I’m glad they published this heart-wrenching personal essay, if only because it lets me know I’m not alone. Within, the author (a tenured prof employed at a large university) tracks their critical work burnout from their child’s illness through impossible hybrid work conditions through sick care and then of course through the pandemic insanity. What I appreciate most about this article, besides the compelling personal account of the toll this job has taken on them specifically, is the clear-headed tracing of the awful working conditions since way before the pandemic, and having nothing really to do with their kid’s illness, though that experience did throw a light on the trouble like nothing else did. The author treats this article like a plea, and a discovery: that they cannot keep going like this. They need to “claim an academic Chapter 11”4 just to survive, let alone thrive.

Yipes. This is from someone with full tenure. Imagine if this author were adjunct.

Bilger, Burkhard. “The Egg Men.” The New Yorker, August 2005. Available: http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/09/05/the-egg-men

This brilliant article switches between the author’s personal impressions of the things he’s researching, and a vivid historical piece describing the specific and unusual subculture of Vegas line cooks. The “characters” come alive in each scene, and there’s just the right amount of personal touch balanced with the thorough descriptions. The structure and cultural commentary is something I’m going for in my work, as is the personal narration.

Bolz-Weber, Nadia. Shameless. Crown Publishing Group, 2019.

This book is a memoir, throughout which Bolz-Weber tells stories about herself as a girl growing up into a woman, through many different phases of her life. She addresses big social topics like religion, sex, misogyny, purity culture, and different combinations of these, all her positions and arguments illustrated and made more vivid by anchoring them in the personal. Some of the memories she shares here are difficult, some dark, and as such are a good model for me picking my own sorrows apart and sharing them as examples in my work.

Nadia appears as a guest preacher often at the church I go to in Denver, and she’s a fantastic sermonizer, compelling writer, but also a stunning and powerful woman, larger than life and compelling personally in a very similar way that I am. Funny enough, I’ve had a parishioner approach me and ask me if we were sisters, right after I had met Nadia for the first time.

Bourdain, Anthony. Kitchen Confidential. HarperCollins Books, 2000.

This is it—the book that made Bourdain a household name and one of the biggest celebrity chefs since Emeril ever said “bam!” I know it’s rather looked down upon in pop culture circles these days, but I don’t care: I love this book. I love the adventuresome stories he tells, I love his implied head-shaking when he recounts his coming of age in the underbelly of the restaurant biz, and I love his narrative voice. His narrator is part jocular bard spinning yarns of a dangerous life, part wise mentor showing you the ropes before you attempt to climb them. This voice is one I want to emulate in my book; not in his particularly grizzled testosterone-soaked way of course, but… actually maybe? The other reason why I include this book here is his balance of personal events with commentary (and research) on how the restaurant biz works.

The way he weaves sociological and business facts in among his personal life tales is a good model for my project as well—I personally find memoir much more readable when the personal stories have a generous sprinkling of research peppered throughout, and it’s how I want my memoir to read, too. More on the personal essay side of the fence than pure emotional memoir.

Brogan, Jacob. “Why Pursue a Career in the Humanities?” The Washington Post Magazine, March 2022. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/magazine/2022/03/14/modern-language-association-convention/

Brogan centers this personal essay on the dreaded MLA conference, and, much like all the others I mention who do so, describes it as a hell of sorts, which arts and humanities scholars might or might not deserve as a punishment for being in this academic business. Unlike the others, though, because this article is written in 2022, he notes how deserted it is these days: “here … hell is empty, and all the devils elsewhere.”

His contemplations of how quiet and depopulated the MLA is this year meander much like he does physically around the hotel halls in his personal narration. He considers why this might be the case, citing the pandemic but also the state of humanities teaching jobs—it’s not just that such a big portion of the conference is now virtual, but that the job jockeying that was such a big part of the event in the past really seems to belong there, mainly because said jobs just don’t exist anymore.

This is a brilliantly written personal essay, where the author leads you through the deserted corridors, reads you titles of empty panels, wryly puns off titles of books purveyed by eerily absent authors, and weaves both personal musings and research (as well as interpretations of that data) to make a bitter, sad, wistfully questioning whole.

Buford, Bill. Among the Thugs. First Vintage Departures Edition, 1993.

This is a book that explores the dirty secrets of what makes certain people violent, but it does so under the guise of a journalist going “undercover” in the soccer hooligan world, attempting to get a good scoop about that scene. He recounts his findings in a personal essay/memoir style, and we find ourselves vividly there with him as he, almost against his will, gets caught up in the infectious action. Buford sticks with mostly description and scene, only rarely taking a moment in reflection or analysis, making his readers infer what they’re supposed to think and feel about the scenes on their own. A similar premise to my book, without the stranger-in-a-strange land aspect that’s so central here.

Doolittle, Julia. “Not a Pretty Girl,” Julia Does A Lot, July 2017. Available: http://www.juliadoesalot.com/essays/2017/4/4/not-a-pretty-girl

In this open-letter style essay, Doolittle narrates her journey through not getting cast and getting cast as men, “weirdos” and other eclectic roles since her entry into theatre as a kid. She, like me in a few of my chapters, particularly Chapter 3, notes that the big parts for women in theatre necessitate classical Western ideals of feminine beauty, and how it feels growing up as an actor hearing that you’re “not a pretty girl” with the understanding that being pretty is the only way to have value as a woman. This theme is a strong and repeated one in my work—I also like the open letter format of this piece, addressing a nameless younger reader. This inspired me to do a postscript chapter in that same style as a curtain call to my book.

Ehrenreich, Barbara, Nickel & Dimed. Picador Modern Classics, 2001.

The subtitle on this classic mockumentary book is: “on not getting by in America.” I call this a mockumentary because it’s not exactly a memoir, in that these shit jobs Ehrenreich recounts aren’t her own. Not really. They’re brief and calculated experiments she takes on in the name of journalism, with a big sniff of condescension. Though widely touted as a monumental work in the field of memoir and in the literature focused on justice for the overworked and underpaid, still. The premise of this project makes my skin crawl: why not get a working-class writer to do this very thing, but from their actual experience, not a middle class dabbler in it for a couple of weeks at a time?

Of course I know the answer to this: Nobody gives a damn about any of those working poor writers, and doubt they can even exist. This is why Ehrenreich “had” to do it, and also why this book was seen and made any difference, if it can be argued that it did. I hadn’t heard about this book, to be honest, until Metro did the theatrical version of it one year not that long ago, and this project of mine is what made me pick up the original. I thought we might have something in common.

To be fair: in the afterword, she does redeem the condescension just a little bit, by talking about how comparatively easy she had it, by calling out her own dispelled prejudices about those who are in the “nickel and dimed” jobs, and by acknowledging the awareness this book brought to the plight of the working poor when it came out. Still though. Yuck.

Gaiman, Neil. The View From the Cheap Seats. HarperCollins, 2016.

I quite like this collection of odd nonfiction snippets—Gaiman is strongest when he’s in his original journalist mode, I think, and it shows here. The personal essays within are the best—the ones where he focuses on himself and an experience, or himself and his own history, or his history with a piece of art. One particular favorite is a diary-like piece where he spends 6pm to 6am in London, recording the nightlife he observes and joins with, each hour. I’d love to do that where I live, but everything shuts down at like 10pm.

Maybe I’ll do it anyway, and call it “6-12,” both after the corner store I used to frequent when I was little, and the hours I’d have to limit my version of this to. I have fond memories of the 6-12 gas station—it was the first place my parents let me walk to by myself, and I remember their Icee knockoffs, called Slush Puppies, were a delicious regular treat. Then I could talk about the places and things and people I do from 6pm till 12am. Yeah that doesn’t sound nearly as cool as Gaiman’s SoHo jaunt, but. I dunno. Might have an appeal of its own.

Germaine, Gogo, Glory Guitars. University of Hell Press, 2022.

This is a lovely nitty gritty titty memoir about the roughest teenhood imaginable, in Fort Collins, CO, not far North from my own dark and strange teenhood in Boulder. I picked this up because I had the sense that Germaine might just have a similar story to mine, in this dramatic memoir about the trials and tribulations and traumas of a punk girl as she comes of age. She is an excellent and lyrical writer, chronicling the sexist society she knocks antlers with as she grows up and gets drunk, along with an almost wistful air of love for her young self.

I was especially moved by the wonderful “where are they now” section at the end, where we see where she is, sort of, now, and a little bit of the bridge between the gorgeous disaster and the still-punk-deep-down adult self she is now. She got here to the punk memoir party first, but that’s okay.

Also, she’s got tons of footnotes replete with band name puns. Which I adore.5

Gottschall, Jonathan. The Professor in the Cage. Penguin Press, 2015.

Another tale of a disgruntled academic, this book veers into a deep social-studies dive of masculinity and why men love fighting so much. I first came across this book as I was completing my Problematic Tropes article series, and was intrigued, since I too am a disgruntled academic and also a martial arts practitioner and enthusiast. Gottschall weaves his own personal tale of entering into the world of MMA as a middle aged, out of shape academic, all the while observing himself doing it almost from outside himself and wondering why. He’s got a lot of the three voices I’m cultivating in my book: the self effacing human telling a personal story, the academic recounting his research, and the reflector/commentator who synthesizes and muses on the two. I quote from this book in Chapter 6, where I talk about why I personally enjoy physically extreme activities that “suck,” and how pain can equal pleasure.

Hogan, Linda. Dwellings. W.W. Norton & co., 1995.

When I was an undergraduate in my last semester of both a BFA in acting and a BA in English, I attempted to add interesting things to my schedule for the last hurrah. Hogan was teaching a poetry workshop for the Masters degree students in creative writing. Undeterred, I attempted to get into the course myself. I applied for a special exception by handing in a portfolio of my work, and was accepted. So, in my last semester of college, I took stage combat and graduate level poetry writing. Obviously both of these courses changed the course of my career and life. As I was graduating, Hogan gifted me a new copy of this book, signed and inscribed. It’s a series of short personal essays: part historical, part autobiographical, and almost prose-poetry-like in their richness and elegance. This is another stellar example of personal essay intertwined with other kinds of non-fiction, and it happens to be one of my favorites of the genre, not only because of the personal nature of my own copy.

Hogue, Seamus, and Peony Rosette. Parallel Bars. Blog: March 2017-March 2020. Available: https://parallelbarsblog.wordpress.com/

This was my first foray, not into blogging, but specifically into the type of writing I would later learn is called personal essay (more than memoir). This blog was co-authored by me and my partner under pen names, and the premise is that we write about ourselves, our lives, and each other when we’re at bars apart, since at that time we didn’t live together even part time, but were mostly living separate lives. The blog began when I, on a writerly whim, wrote about myself sitting at a pub as though I were a narrator in a novel, describing myself as a main character, in third person omniscient POV. It took the form of a paragraphs-long text message to my partner. He responded in kind, as he happened to be at a cigar bar himself at the time when he received it. Those original messages don’t exist anymore I don’t think, but it was that exchange that gave him the idea of Parallel Bars, named cleverly that way because that was the writing situation.

It’s a trip, to go back to those first entries and see the hesitant way I dip my toe into the memoirist waters, and the confident way he writes about especially his past bar experiences in his life. It’s sometimes quite difficult to read how much pain we both were in at that very rough time in our relationship, and odd to see the fear of utter doom in those last posts, as Covid lockdown did indeed loom and crash upon us and we had no vision of what, if anything, would lay beyond that. But it’s also heroic (and fricking exhausting) to watch the two of us, through our often forcedly wry words, work so very very hard on our healing, ourselves, and on us. Whew…6

Kay, Andrew. “Academe’s Extinction Event,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, May 2019. Available: https://www.chronicle.com/article/academes-extinction-event-failure-whiskey-and-professional-collapse-at-the-mla/

This is almost a sequel of sorts to “Pilgrim at Tinder Creek.” Its subtitle, “Failure, Whisky, and Professional Collapse at the MLA” says it all—he treats this discussion of the toxicity of academic job hunting (especially in the humanities) as a torturous obstacle course of sorts, wherein he attempts to heroically enter the fray and exit victorious, but instead fails painfully. He doesn’t just describe how awful the experience at the MLA is for all, he puts himself there in the middle as a character, and therefore puts readers there too. This, like my piece, is mostly a personal story, with buttresses of research thrown in for support.

Kay, Andrew. “Pilgrim at Tinder Creek,” The Point, February 2017, Issue 13. Available: https://thepointmag.com/examined-life/pilgrim-tinder-creek/

Kay’s essay on academia and dating is a direct inspiration for my book—in this essay, he parallels online dating with English professor job hunting so deftly, describing the emotional pain of each with such wry self deprecation, that I am often a bit angry when reading it. It’s so dang good. He’s doing what I want to be doing in that he’ll weave a description of each of his threads together beautifully with the support of researched statistics and a touch of his own emotional perspective/conclusions in perfect balance. And of course, any reader of personal essays and creative nonfiction will recognize the play on his title with one to a piece of creative nonfiction that’s maybe a little more famous…7

Mantell, Sarah. “Touch the Wound, But Don’t Live There.” American Theatre, August 2021. Available: https://www.americantheatre.org/2021/08/18/touch-the-wound-but-dont-live-there/

Mantell recounts her own physical reaction to serious trauma, and relates her personal experience with the widespread norm of the suffering artist (particularly the performing artist). Her subtitle is: “why we need resilience services as much as we need fight choreography.” It pinpoints the process actors often go through in order to produce excellent, personal art. This has been useful to me especially in my concluding chapter—I learned to exit the intensity of traumatic artistic performance with drink, in the ‘90s. But Mantel’s prescribed solutions, almost akin to a BDSM aftercare process, sounds way healthier.

McGowan, Rose. Brave. HarperOne, 2018.

McGowan’s memoir begins with a raw declaration that she’s writing her story specifically because she wants to help others who have been victimized in similar ways to her, as much as take down the (mostly) men who are the perpetrators of the abuse she details. Same here. McGowan starts with a frank and horrific description of her early childhood in a cult, then moves forward through time to the events that occurred during the time of Ronan Farrow’s research into the widespread sexual abuse in Hollywood of which she was one survivor. Throughout, she weaves feminist cultural commentary amid her own specific personal story, and often interrupts herself, almost like she’s back there in the memory she relates, yelling at the people abusing her, asking why, saying how dare you do this to me.

Schwartz, Laurence C. Teaching on Borrowed Time—an adjunct’s memoir. Page Publishing, inc. 2021.

I’m a member of a couple different groups on Facebook that center around the adjunct plight, and one day I came across this author encouraging us all to buy his book, on one of them. Wow, I thought: Another adjunct in theatre, this one having 30 years under his belt of this abusive academic life, instead of my 20–I definitely wanted to see what his experience has been like. And in his opening paragraphs, he discusses Escape From Alcatraz and likens his adjuncting to its themes: “I’ve survived but have given up any hope of escaping. I am a lifer.”8

It turned out to be an example of what not to do.

I was surprised by Schwartz’s relatively mild descriptions of various unfairnesses, unbalanced by some self-congratulation as to his theatrical career and the amazing people he’s been honored to work with over the decades. But what astonished me most was the very end, where he almost explains away, or definitely at least shrugs off, a lifetime of horrible treatment, and worse pay. He blithely just says something close to: oh well, I love my job—how fulfilling it is to teach and to influence young people; I’m glad I’m still here. It disturbed me in a similar way that listening to a brainwashed cult member does.

Smith, Patti. M Train. Vintage Books, 2015.

Smith has written a few gorgeous memoirs, and this one is probably my favorite. It’s lyrical and poignant, having been written in the wake of so much loss, including the deaths of her husband and her brother, but it never gets so heavy as to be too dark to read. Her brilliance as a musician shines through in her personal writing here. I add this to my list because I admire the way she discusses experiencing strong, even overwhelming, emotion without ever putting herself in the light of weakness. It’s a beautiful, strong piece of observant memoir that I look up to.

Tevis, Joni. “Warp and Weft,” Places Journal, May 2015. Available: https://doi.org/10.22269/150511

Like Kay’s pieces, Tevis does a thing with this essay that’s pretty much what I’m trying to do with my book. She weaves threads of personal story, historical research, and cultural commentary in a similar way that I’m going for. In fact, I kept going back to this piece as a model for my book as I revised, both for structure and content (as far as mixing memoir and research). Like the textile topic of the piece, the various threads of narrative are given in specific strands that contribute to the whole. It really does read like a piece of weaving—it’s a masterful example of what’s being currently called a “braided essay.”

Wheaton, Wil. Still Just a Geek. HarperCollins, 2022.

Just a Geek was an early version of Wheaton’s memoir—published from adapted blog entries and made into a book around 15 or 16 years ago. Now, he has taken up that old book and has annotated the bejesus out of it. Footnotes, additions of blocks of text, ruminations, musings, arguments with, and apologies for, his older work makes this memoir twice the size of the original, and three times as engaging.

Far from being annoying or making the narration choppy, the plethora of annotations in this book doesn’t distract or dilute the message of the writing, but enhances it, deepens it, gives us the (sometimes literal) backstage view of a life lived in fame.9 It’s a difficult balance, to talk about oneself and one’s immense talents and achievements, and self-deprecate about same, without coming across as either arrogant or insufferable. Wheaton comes across as neither, but the reader is moved by his honest examination of not only his life stories, but his (sometimes problematic) earlier recounting of them.

WORKS CITED

Some of the selections in other categories are sources I’ve quoted from as well, but these are only here because a direct quote or paraphrase of an original concept from them are in my work, and they don’t meet the criteria of any of the other categories. These are an odd eclectic collection of very different types of writing, which I guess tells you the kinds of strange experiences I’ve had throughout the bits of my life I’ve relayed here.

~

Berlant, Lauren. A Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press, 2011.

This book is a dry, academic read—dry as eating a stack of saltines with nothing to drink. But I wouldn’t be an academic adjacent writer worth my salt if I didn’t talk about Berlant, even a little. I feel like it’s a necessary part of daring to do cultural commentary as a marginalized person. Plus, their concept on which this book is focused and titled (Cruel Optimism) is hugely important to my work—I have had a major problem with toxic positivity as a life obstacle for a long time, and working through my own trauma in my own book has a lot to do with giving up the Cruel Optimism so rampant in the world to embrace instead a powerful pessimism. I’ve introduced this concept and have quoted from it in Chapter 2, and have titled the chapter after the book.

Childress, Herb. The Adjunct Underclass. U. of Chicago Press, 2019.

Not only the useful (and chilling) data about adjuncts throughout this book, but especially the last chapter, is the direct inspiration for and very reason I began this project in the first place. Childress equates academia with a cult in that last chapter, which opened my eyes to the parallel of my marriage with my career as equally abusive, in specifically the same gaslighting way. The second reason I want to include this on my list is the interweaving of the tale of the alewives with the stats of a particular business model of the university—I like the intertwining of research with the interesting local environment story.

More than a work I cite, the whole concept of my book was sparked in my imagination by (especially the last chapters) of Childress’ book. This quote was one of the biggies that made me say “waaaait a minute” to myself:

“A life of contingency, like any life with an abusive partner, requires us to manufacture elaborate emotional defenses. We … are uncertain even of our most basic survival if we were to leave, knowing that a few thousand dollars per course is horrible, but having no other readily visible market for our labors. Participation in contingency may look like weakness, but it’s an attempt to gain control, to claim a tenuous foothold on the raw, crumbling face of the chasm.”10

College Factual. Media Factual, 2021. Available: https://www.collegefactual.com/search/

This is a stats site where I found the numbers of how many adjunct faculty are employed at ‘Subway University’ of Denver. I found that 62% of faculty there are adjunct. I didn’t look up DU, the other school where I still teach, because I happen to know the department for which I teach employs adjuncts only, for all its faculty.

Cristol, Hope. “What is the Spoon Theory?” WebMD, 2021. Available: https://www.webmd.com/multiple-sclerosis/features/spoon-theory

Cristol gives a basic rundown of what Spoon Theory is, how it originated and how its related jargon is used today. I first learned about Spoon Theory from my friend who lives with chronic illness related to autoimmune disease, and since hearing about how it works from her, I’ve seen countless online friends talk about being “out of spoons” in reference to everything from physical illness to mental breakdowns. Being a classic Gen Xer, having grown up in the training scenarios I was, and having been mercilessly bullied my whole life, I have had to make a concerted effort to appreciate Spoon Theory. For me: like, yeah okay if you have something like MS then, sure. That’s valid and I get that you literally can’t cope some of the time; that makes sense. But when it comes to mental health? I remain in my unhealthy and unrealistic Gen X stoicism. No more spoons? Who gives a shit. Get more spoons. Use forks instead. In my archaic tough-bro brain, running out of spoons is not an excuse.

I’m working on this, don’t worry. Oh, and I reference this in Chapter 6, when I discuss pain, pleasure, violence, and getting the fuck up.

Druyor, Gwendolyn, Geoffe Kent, and Jennifer Zukowski. “More Metal; Less Art.” Colorado Renaissance Festival 1997, On Edge Productions.

I quote from my memory of one of these scene scripts in Chapter 5, though the RenFaire scripts were largely based on improvised banter, movie quotes, and dick jokes as opposed to much original dialogue. To be fair: banter, movie quotes, and dick jokes were pretty much the way we all talked to each other normally anyway. But there were, each year, still a collection of relatively complete scripts for each of the 9 fights we performed per day, with full choreography notation to go with each. So each year, each actor-combatant would get a packet of scripts and choreography, separated out and numbered to pair together. The stage directions in the line script would be enough to indicate which moves would be done where, but not the full details. The choreography scripts would be lists of only the movements, with occasional brief line indications in places where the lines were a cue to the moves or in other ways directly connected.

1997 was the first year I was part of the Band of Young Men (On Edge Productions), and I was added to the fighters that were already in charge of the scriptwriting. It was largely recycled from previous performance years, though each year tended to have a theme when it came to which movies we quoted from. ‘97 was a combination of Army of Darkness and Princess Bride mostly, with some Shakespeare and other things sprinkled in, including Aliens, as quoted in Chapter 5. In 1998 I returned, this time dressed in a dress and corset, and I was mainly in charge of the scripts that year, with lots of help from Geoffe Kent, who was second in command in ‘97 but the main choreographer and leader of the Band in ‘98. That one was called “Enough Talk, We Fight!”

Firewater. “6:45 (so this is how it feels).” From: The Golden Hour, 2008. Lyrics available: https://g.co/kgs/HnBPBz

This song’s lyrics were the center of the theatre piece I describe in chapter 8, and I quote large chunks of the song’s lyrics throughout the chapter, interspersed with text, to invoke the way it sounded when it was developed for devised theatre piece I Miss My MTV.

Haas, Sarah. “Jenn Zuko and the Art of Violence, and Sex, Onstage,” Boulder Weekly, November 2018. Available: https://www.boulderweekly.com/entertainment/jenn-zuko-on-the-art-of-violence-and-sex-on-stage/

I mention this article and the process of its creation in Chapter 1. It’s an overview of my work in stage combat and especially intimacy coordination. Haas gets a lot of the facts about the play we discussed quite wrong, but other than that, her overview of me and my work is a decent bit of biography, of some of the many interesting things I regularly do in my life. It’s also fascinating to read this in the context of my own examination of the many times I’ve been over-admired, put on a pedestal, etc. People love extraordinary people, and love to read about those who do extraordinary things.

Kluger, Jeffrey. “Domestic Violence is a Pandemic Within the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Time, Feb. 2021. Available: https://time.com/5928539/domestic-violence-covid-19/

This article gives the data on domestic abuse during the pandemic lockdown, and illuminates said data with case studies from both abuse victims that escaped their abusers, and unfortunately ones who didn’t, fatally. I mention these statistics and quote from this article in Chapter 9.

McCulloch, Gretchen. Because Internet. Riverhead Books, 2019.

This is a rollicking read into the linguistic story of the evolution of language, specifically the ways language (including pictorial language like emoticons and emoji) exists and has changed online. Linguistics is one of those fields that I’m not necessarily an expert in, but that I love to nerd out about, ever since I was obsessed with Tolkien’s languages in Lord of the Rings, in 4th grade. McCulloch gives an overview and a rundown of how chat room “talk” is different than other written communication and also different than spoken language. It’s something else, or something in between. She goes into it all, including emoticons, emoji, text abbreviations, and even memes.

I first heard about the concept of the Third Place in this book, funny enough, and not in Ray Oldenburg’s original study of it. The idea of the virtual Third Place was a compelling one to me, and from McCulloch’s discussion of online versions, I went to Oldenburg’s. I’m still fascinated by this concept and have a whole idea laid out about the Third Place in a pandemic. Maybe that’s the next book of braided essays. But I do run down the Third Place rabbit hole a bit in my epilogue when I’m talking about Metro’s main theatre classroom and its attached hallway gathering place.

Oldenburg, Ray. The Great Good Place. Da Capo Press, 1999.

This is the OG sociological work on the concept of the Third Place: what it is, how it functions, why it’s important for a healthy society, etc. Oldenburg describes how a Third Place works well, and also goes into the difficulties in finding them in an America that’s largely suburban and car-centered. He gets a little crotchety for my personal taste, and even veers close to sexism in one of his chapters, but I write that off to being old himself and a little out of date. What McCulloch does in her book is to show how the Third Place has expanded to include different things in an online and computer centered society.

Again, I’m fascinated by the Third Place concept and plan to write more about specifically that. But in this book, I dive into the shallow end of the concept in my epilogue when I describe the Third Place as it manifests in Metro’s theatre department. You can see yet another reason why my leaving was difficult, and emotionally tumultuous for me. I was giving up a vital Third Place of mine, that had betrayed me.

Sano-Franchini, Jennifer. “Co-Dependent Emotions on the Market,” CCC 68:1, September 2016.

Sano-Franchini parallels the turmoil of emotional labor related to dating, to the same in the academic (particularly English and comp) job market. Less personal essay in nature but more fully academic and researchy, this article lays out the harshness of both dating and academia as clinical problems, resulting from economic issues with the US and the morphing and (she suggests) downfall of contemporary academic institutions. It’s a stiff read but it does address a similar braiding of two of the strands that I do, and it’s from this article that I discovered Berlant’s concept of A Cruel Optimism. I mention this article in Chapter 2.

Tanemura, Shoto. Ninpo Secrets. Genbukan Honbu co. ltd. 1992.

This is one of two major sources of information about the particular branch of ninjutsu, or ninpo, called Genbukan, that my ex husband studied under. Tanemura-sensei is the teacher of his teachers, and as such, my ex did actually get a few chances to train with Tanemura himself back in the day. This book goes into detail about the historical and cultural background of the ninja, and a little bit into how the structure of the schools of this martial art work. The other source (which I can’t find for under a hundred bucks, unfortunately) is more about describing the actual techniques. I talk about ninja stuff in chapter 8 mainly from my memory of personal teaching from my ex and others (so I don’t really technically quote from it), but this book is immediately up there in our dojo’s lineage, and I studied from it in depth when I was in training full time. The concept of shikin haramitsu dai komyo is found here, as well as kusa, which are central parts of my Chapter 8.

Zuko, Jenn. “Problematic Badass Female Tropes #6: One of the Guys.” Writers’ HQ, 2017. Available: https://writershq.co.uk/problematic-badass-female-tropes-6-one-of-the-guys/

This was the penultimate article in my Problematic Badass Female Tropes series, and it’s the core on which I based the chapter of the same name, Chapter 5. I reuse some of the same events in the storytelling parts of the chapter, even having recycled large chunks of that text, though I don’t move much further from there into cultural criticism and media analysis the way I do in the article.

OTHER

These last resources don’t fit into any of the previous categories, but all were anywhere between inspirational and directly influential to my book. Some are just examples of good nonfiction writing that doesn’t go into the memoir, self-help, or other genres I’m mixing in my work, but may have a flash or fragment of one or more of them. Others may have touched on a concept important to my work without centering on it. All of these, like my Works Cited selections, are a strange list of weird stuff, which tells you something about the components I’ve used for my particular bird’s nest.

~

Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas. Why do so Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders? Harvard Business Review Press, 2019.

If one can sift through the morass of typos (did this book have a copy editor, or?) the throughline of Chamorro-Premuzic’s thesis is highly entertaining, and somewhat heartening to boot. He’s calling out the especially Western leadership ideal of the self centered, usually white and cis-het, power hungry and dominating man as the guy who’s always the one in charge.

Chamorro-Premuzic lays out the data, showing that though this type is most often chosen for launch into greatness, that in fact that sort of leader isn’t effective at all, and is the reason for bad performance in most cases. Chamorro-Premuzic also shows how EQ (emotional IQ) and women in leadership actually makes companies do better and results in a happier, more productive workforce. Unfortunately, he shows, this odd idea of the Gordon Gecko/Don Draper leader is so steeped in our culture, it’s a catch-22 and a conundrum that he really can’t seem to find a solution for.

This is why I didn’t put this book under Self-Help, though it does kind of read like one—there’s not really the help aspect here, more of a detailed rundown of the problem. It feels a bit like the kid shouting that the emperor has no clothes, in that it seems like nobody is really talking about this specific problem of awful men as something to be solved, merely as something that’s just the way things are. But the author does hesitantly offer a little hope, in his last chapter, in a cautiously optimistic noticing of workplace attitudes changing. And, #metoo-like, he notes that the doxxing and elimination of these terrible yet powerful men is indeed beginning (or continuing).

“With the world’s greater awareness of the problems of toxic leadership, people like [Uber CEO] Khosrowshahi will be more likely to become the preferred leaders—even when they are men.”11

I include this book because it speaks to the sorts of leadership structures that are in place all over, not just in corporate America but in academia as well. It shows how a lot of working culture across the different colored collars has come to expect to be abused by these types as just par for the course. My partner was reading this book at the time of this writing—a book that was being quietly circulated around his own workplace, and I found it intriguing enough to pick it up and add it to my list. I’m fascinated by the number of business books that have been a direct help and/or inspiration to me through this process of navigating an exit from an adult lifetime of an academic career. It’s teaching me not only about the world I’m attempting to enter, but about academia as well—the academic world is pretty bureaucratic, poisonously so, and it’s been good to not just realize that, but see the hard data about that fact.

Dolezal, Joshua. “The Big Quit.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2022. Available: https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-big-quit

There’s a new subgenre of creative non-fiction in town, that had a heyday in 2020 and only keeps expanding. It’s called “quit-lit,” and it’s comprised of personal essays and books of memoir chronicling an academic that quits academia to find work in greener, better paid pastures. And there are way, way more of these true stories than might be imagined. This article is one of the better examples of the quit-lit subgenre that I’ve read in a while. It’s not exactly a personal essay, though Dolezal does talk candidly about his own leaving of a faculty position, nor is it solely a sociological case study of an economic trend, though he does recount several quitting academics’ stories here alongside his own.

The subtitle of this article is, “Even tenure-line professors are leaving academe,” and that’s the central thesis and theme of Dolezal’s thoughtful, questioning piece. Sure, he reminds us, adjuncts and other contingent faculty have been leaving higher education for a while now, especially in the company of the pandemic-wide Great Resignation happening in other fields. But now, Dolezal shows, even those in the hallowed roles of tenure, those faculty who can never be fired, who have their cushy intellectual job security with all the leave, benefits, and office space their adjunct equals never did, are jumping the academic ship. He describes why the examples he talked to left, what they did next, and muses about the whole messed up situation. He lists the reasons that may not be obvious to a non-academic layperson: the shit-low pay (Yes, Virginia, even for tenured professors), the blatant racism and sexism rampant through too many universities, and the sad situation that it looks like these days, higher ed is focused on everything but education.

One quote from one of his interviews hit me hard in the gut, with such an accurate wording of what it feels like to have a teaching calling, and to strive in a place that does not value that work whatsoever: “The ‘prove yourself or else burden’ eclipses the calling part of it.”12 Ouch. And yes. I’m struggling with these feelings during this writing, as I slowly but surely drag myself away from the rusted trap myself.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. Bright-Sided. Picador, 2009.

This book was suggested to me as a slightly less dry read on a similar topic to A Cruel Optimism, but it’s really a different monster—it’s mostly cultural commentary in the form of scathing, sharp history lessons, all surrounding the problem of toxic positivity in today’s (especially American) society. Ehrenreich does a great job of keeping the judgment bits to a minimum—she lays her argument out clearly, letting us get our own conclusions from it, then will tack a sort of moral to the story sporadically here and there, just to make sure we’re getting the lesson she wants us to be getting. But the main reason I’m adding this book to my list is her chapter 2. Chapter 2 is titled, “Smile or Die: the Bright Side of Cancer.” In it, she recounts her own personal experience of undergoing a breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, and weaves around her own story that of the poisonous pink paraphernalia rampant in breast cancer awareness, events, and even the doctor’s office itself. She’s doing what I’m attempting to do quite well here—not overwhelming the reader with the heavy story, and not inserting her current attitude of her experience too much or too soon. I went back to this chapter as a model as I revised for voice.

Farrow, Ronan. Catch & Kill. Little, Brown & co. 2019.

Farrow’s award winning expose of not only Harvey Weinstein’s history as a sexual abuser, but the rampant sexual crimes throughout that whole sphere of the show/journalism biz, is a read that leaves one breathless. I include it here because, though it’s mostly research, the bits of autobiography that Farrow does insert here and there grounds the whole story, like pins in beetles on a display. Plus, the more I can read the best of the excellent non fiction/essay writers out there, the better.

Friend, Chris. “Scholarly Communication,” Teacher of the Ear. Hybrid Pedagogy, October 2021. Available: https://hybridpedagogy.org/scholarly-communication/

In this podcast episode, Friend talks with scholar and podcaster Hannah McGregor of Feminist Agenda and Witch, Please about the role podcasts can play in scholarship and specifically, academic research. There’s a section in this highly edutaining conversation where McGregor discusses the myth of Next Time when it comes to the hope of promotion within academic jobs. She uses my and Berlant’s language to rail against the unfairness (and bait and switch aspect) of trying to make it in an academic career. It seems to be academia’s best known not-so-much-a-secret, that moving up in the ranks is impossible, and that the rules for doing so are classist and unavailable to most.

Leiber, Fritz. Ill Met in Lankhmar. White Wolf, inc. 1995.

Though a lifelong Fantasy and Sci-Fi fan, having loved the big fantasy works of Tolkien, McCaffrey, LeGuin, and Herbert since 4th grade, for some inexplicable reason I had not encountered Fritz Leiber’s riotously rich sword-and-sorcery world of Nehwon until the Mignola-illustrated reprints came out in 1995.

Well, maybe there are some explications possible: for one thing, I had never been a huge comic book fan, which means I had skipped the childhood Conans and Krulls and so missed that particular subgenre in my copiously Fantasy laden kid reading. Also, and maybe connected to this: though I had very much enjoyed works like Dune in junior high, the more gnarly sexual stuff or extreme adult dark works like those of Lovecraft13 had been well under my radar. Once I finally, after college, found “those two dubious heroes and whimsical scoundrels, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser,”14 I immediately fell in love. No lofty Aragorns or old wise Gandalfs these, nor even stoic Geds, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser are barely more moral than the “bad” guys, if they’re even that. They’re sexual deviants and wild drunks, skilled thieves and brilliant swordsmen. I’m not sure they ever really win the day, though they don’t get killed in their various defeats by various twisted and perverted antagonists (though they have journeyed into the land of Death). This series of short stories and novelettes culminate in the Twain meeting their soulmates, but without losing any of their wry wickedness, and without any female character weakness or fridging. The stories have many flaws and are crunchy enough that I doubt they’d be published today, gritty fantasy worlds trending though they are. I absolutely love them.

I was inspired by the way the story/chapter titles are done in the whole series: we’ve got the title, then a witty and pithy description, though not really a summary, below that. These amazing Victorian-esque blurbs run between a sentence and a full paragraph, and I’ve loved that setup ever since I first encountered it. I wanted to have something similar for my life story’s chapters here.

McClure, Kevin R. and Alisa Hicklin Fryar. “The Great Faculty Disengagement,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, January 2022. Available: https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-great-faculty-disengagement

This article compares and contrasts the dynamics of the post-pandemic Great Resignation in fields like hospitality with what’s going on in the ranks of higher education, particularly its faculty. Faculty aren’t leaving their jobs in droves the way some in other fields are, but what is happening is that we are ceasing to go above and beyond in our jobs. Instead of striving and doing a bunch of extra unpaid professional development and course engagement work, now faculty are doing the absolute bare minimum. This, according to the authors, has resulted in a spooky air of a ghost town in university-land. There’s a whiff of disengagement across campuses and it’s affecting not only the quality of the education, but the mood and even the wellbeing of students and faculty alike. Administration just doesn’t seem to get it, and I won’t be surprised at all if teachers of higher ed start to collectively jump ship the way schoolteachers have begun to.15

This article resonated with me greatly, in that I’ve been musing during the whole pandemic-time, that it’s felt so ironic that my crappy job was still as intact as it ever has been, while lots of people that I know, particularly in the arts, lost their jobs completely. Not that it has made my job at all more stable, or that I’m being treated any better, and I certainly have not gotten any iota of a raise or promotion. I do feel that impact, though, of the Big Quit in other fields (even those related to teaching), and I see its results and implications on enrollment as I continue most of my academic labor.

Newitz, Annalee. Four Lost Cities. W.W. Norton & co. 2021.

This is a history/science overview of four ancient abandoned cities, where the cultural and historical (as well as anthropological) contexts are discussed, surrounding the main question of why these cities were abandoned. The answers Newitz finds suggest new and in-depth questioning of our assumptions of why any ancient metropolis gets abandoned. The reason I include this book here is in how Newitz’ narration is structured: they discuss mainly the historical events and stories surrounding the cities, but they also describe their own personal reactions to seeing the ruins, snippets of their interviews with the archaeologists involved in each site, and even tells a personal story or two that relates to what they’re experiencing within the research. It’s a surprising and engaging personal addition, making for an even more compelling read than it would have been without.

Polak, Brian James. “What Makes Gina Femia Run,” The Subtext. American Theatre. October 2021. Podcast episode. Available: https://www.americantheatre.org/2021/10/27/the-subtext-what-makes-gina-femia-run/

In this episode of The Subtext, playwright Brian James Polak interviews award-winning playwright Gina Femia about her journey through the world of theatre. Femia talks about the rough, abusive system that is the theatre, and even goes into detail paralleling two of her relationships that were abusive with the abusive system of theatre (obtaining an agent, etc.). She even brings up the concept of gaslighting and how the world of theatre is very much a relationship with a gaslighter. It’s nice to hear from a theatrical artist that I consider to be more established than me going through exactly the same thing I have. Hm. Maybe that means I might not be so far behind the “successful” after all?

Pullman, Philip. Daemon Voices. Alfred A. Knopf, 2018.

The subtitle of this collection is: on stories and storytelling, which is why it was such an influence on my book. Now, I’ve always very much enjoyed Pullman’s His Dark Materials fiction series—it’s a work of deep, intellectual High Fantasy that I wish I’d had back in grad school to wave in the faces of those denigrating the genre as intrinsically lowbrow and commercial, as opposed to high literary quality. But this collection of nonfiction is almost more excellent as far as brain food than his fiction was for me. Especially stellar are his pieces on Milton and Paradise Lost, not to mention his sort of behind the scenes pieces telling stories about the making of his novels.

These essays are actually mostly speeches from various awards and other events he’s been asked to speak at over the years, and it reminds me of when I saw him read in person at Boulder Bookstore several years back: he did his bit about the process of writing, where he describes beginning with a lot of yellow post-it notes, then lots of research with xeroxed pages, etc. And then the final step he describes is to throw all that work out the window and write something fresh that you have no knowledge of. The essays (and speeches) in this book are so engaging, and I can hear his drily witty English accent so clearly as I read, I feel like I’m sitting at a pub with him, exchanging brain fodder and exciting the old neurons together. I hope that my own presentation/speaking voice comes through as clearly and as charmingly in my own work.

~

Cloud, p.90

Lopate, p.91

Available in Zuko’s Musings.

Anonymous, n.p.

“Which I Adore” is my She Wants Revenge cover band. Ahem.

When PB went defunct, I began my own pen name blog solo, called A Rose is a Rose, over at https://peonyrosette.wordpress.com/ mainly because not only was I feeling fed and fulfilled by my personal writings at PB, but because I had gotten praise for some of those essays. I don’t feel like it’s as strong as the duet blog, though, even though I’ve adapted and shared work from that one and not the other.

“Pilgrim at Tinker Creek,” by Annie Dillard.

Schwartz, p.9

See? It can work!

Childress, p.162

Chamorro-Premuzic, p.175

qtd in Dolezal, n.p.

Fun fact: Lovecraft was a pivotal figure in the editing and advising phase of Leiber’s early drafts of the Fafhrd and Grey Mouser stories.

Leiber, p.24

Honestly, it seems like they kind of have.

NOTE: in view of the recent (2025) information about Neil Gaiman's horrific behavior having come to the fore, I have eradicated him from my bookshelf. However, I feel it would be dishonest if I deleted the 'View From the Cheap Seats' entry from my list of inspirations. Because it was (and in some ways, still is) inspiring as a collection of weird little creative nonfic bits, which is exactly what I write and what I want to write. Anyway. So. For what that’s worth.

Not sure what to do with that, tbh--I never liked Harry Potter enough as literature to care about Rowling's descent, so that wasn't a problem for me. This is a matter I have to look at, as, unlike Alice in Wonderland, this awful person who happens to have created works I like, is still alive. I shall think on't.