Next Time

10 (Outro) Put Out the Light

In which I give a summary in the vein of a Where Are They Now segment from a TV series. To wit: there’s a thing called “hoovering” which abusers will do to their victims. Here I show how I’ve been hoovered and also not. How life has gotten quite a bit better. I’ve come a long way, baby, and I still have a long way to go.

~

AUTHOR’S NOTE: In this chapter, for Substack publishing purposes, I have changed the names of most institutions and individuals mentioned, or have left out their names entirely.

Outro (Chapter 10)

Put Out the Light

“...and then, put out the light.” ~Othello

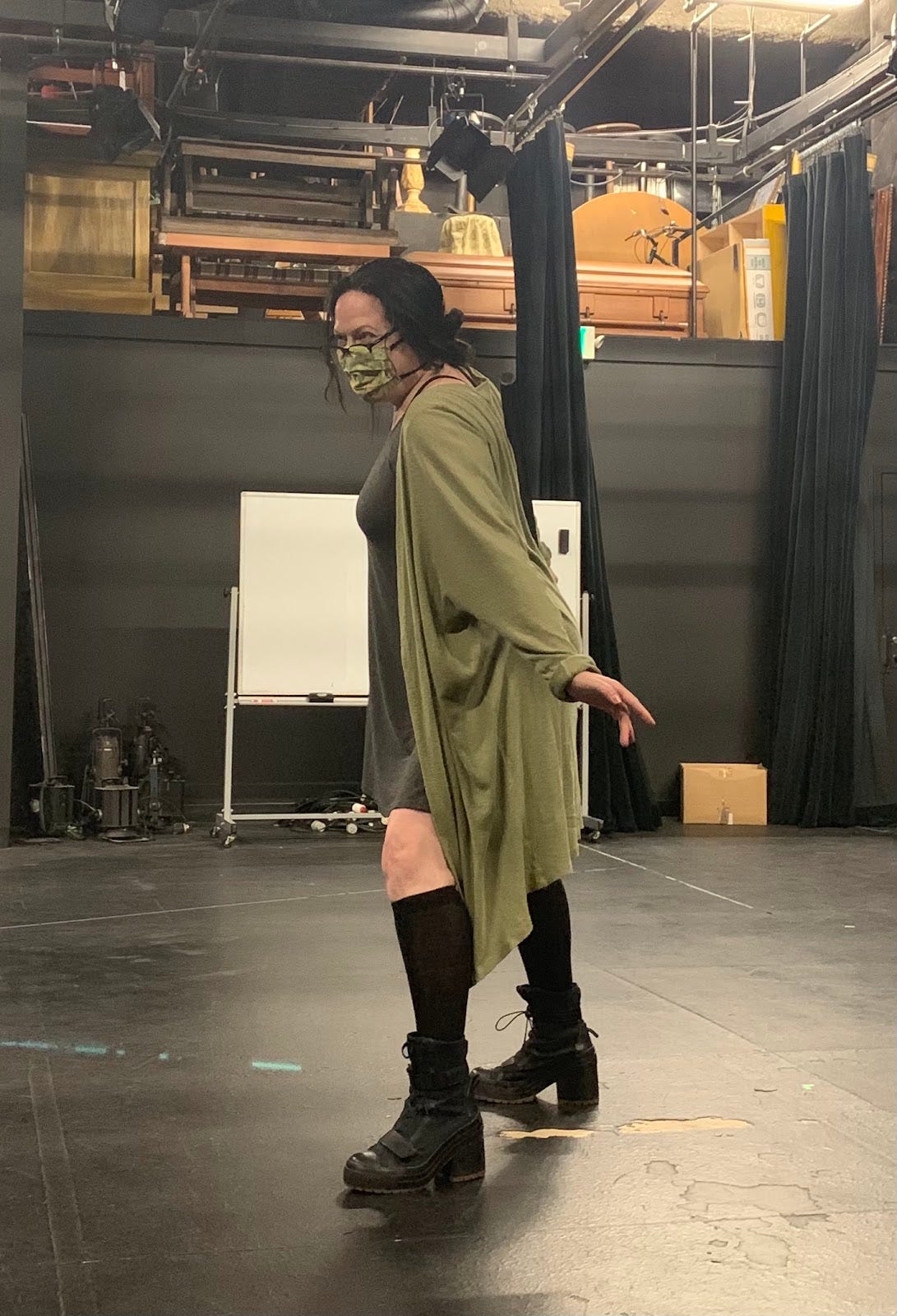

“Can I just say…?” One of my students in the 2021 pandemic version of stage combat class was a tiny young Russian American—she raised her hand to ask this question during our staff unit. I had just been demonstrating a trick for how to more easily catch a twirling staff from behind one’s back. “You looked SO badass just now. Could you do that again?”

“What, me?”

“Yes! Just: your boots, and that pose with the staff. You look SO cool.”

I did the pose again (okay yeah it actually did feel pretty cool now that she mentioned it), and the admiring student took a couple pictures of my awesomeness. I did a little spin and twirl and secondary pose, too, which made her and the other students ooo and ahhh like they were watching fireworks. One of them took more pictures.

Later, as I edited the pictures, I thought I looked a little too fat in the belly for my own personal tastes, but the girl was right—the poses did look badass, especially with my high Converse boots and flowing Jedi-like cardigan, the same color as my eyes. The undercut to my hair made me look extra tough, like a punk or a samurai.

I was not expecting her lovely outburst, but it was a nice ego-boost. Teaching the modified stage combat curriculum had been good this semester, but a bit trying—masked exercise isn’t ideal, though adding the six foot staff back onto the syllabus was a lot of fun. It ended up being most of the students’ favorite weapon that semester—even more than the lightsabers, which was a surprise to me.

After more than twenty years teaching at Subway University, I was still adjunct. They called it affiliate faculty there for a while, but it’s the same thing—I don’t know if they felt like the word “affiliate” would make us feel better about our plight, or if they awarded us that in place of a raise at some point—the exploited years blend together in my memory. But then right after I quit, they changed it back anyway. They’d hired a new tenure-track faculty only a couple years before my exit; of course I applied for the position myself but didn’t get it. I had hoped they’d put someone in that job (if it couldn’t be me) who was from a more diverse background than the rest of us. We were, frankly, a bunch of white people, mostly men. Quite the colonized view of theatre arts, as they put it these days. And, though I wrote the stage combat textbook that their theatre department has been using since I started there in ’05, I had been adjuncting since ‘01 and had no illusions of job security whatsoever, regardless. But a part of me still believed in the possibility of a promotion. It had happened to two of my male colleagues before. Two tech guys.

They instead hired a perky blonde in her 30s to take the job. A bouncing little barrel of bubbles with a specialty in theatrical movement, and some experience in stage combat. Was that the beginning of the end for me? Hard to say. It sure turned my head, and that along with me being fully divorced and on my own combined to give me more incentive, balls, and drive to leave.

The woman is delightful, don’t get me wrong: a very talented artist whose expertise is in clowning and creating devised-theatre pieces like what I Miss My MTV was. And that’s great. But. I’d be lying if I said that I never winced when she introduced herself as “Subway’s movement teacher,” or that my teeth didn’t grind when she took over the faculty advisor position presiding over the stage combat club. Of course she did: I wasn’t allowed to be the primary advisor of the club, as I was only an affiliate. Before her, our tenured head of tech was the official advisor of the club, which meant I was the primary, active (actual) instructor of the group, as I was the only one there with the expertise. So, at that time, it was still ostensibly my club, originating from and consisting of students who wanted to continue to learn these arts from me specifically, after the class was over. They were my own little official dojo, and we had an actively performing group from 2008 on, till lockdown. A core group of about 5-7 students, as many as 10, with others that would come in and out. A thriving, active, healthier version of my ex-husband’s dojo, and non-toxic in its masculinity, unlike the Band of Young Men.

Then, in late 2021, I received one of those school-wide emails, through which, in a celebratory and not entirely un-self-congratulatory tone, the president of the university described a new series of stipends that were about to be deployed. Some payments were going out as sort of sign on bonuses for new faculty and staff; and others, of a slightly less amount, would go to all staff and faculty that stayed on during the worst of the pandemic. A series of one-time “welcome” and “thank you” payments, respectively.

Only a few years ago, I would have gotten excited about this unexpected windfall. Now, however, I seemed to have learned a few lessons. I, upon receiving this email, immediately contacted my department chair. I inquired of him whether this new series of stipends would be going to us affiliates. I mean, it did say “faculty and staff” in the email, after all. He didn’t know off the top of his head and so did some inquiries of his own. I did not hold my breath as I waited for his results.

And it’s good I didn’t, because he replied the next day, saying that affiliate faculty would not be included in that stipend rollout. I didn’t ask him why the hell we’d gotten the email in the first place, only thanked him for checking. So apparently at Subway U, affiliate/adjuncts don’t count either as faculty, or as staff. Even though we make up 62%1 of the total professionals who teach at the school. What does that make us, then?2

To give the chair some credit, he did make mouth sounds for a while about continuing to have me teach stage combat. But he’d already given Professor Bubbles my stage movement class without telling me. And of course he wouldn’t have been able to offer it very often, you know, because of enrollment. Oh and then? He wanted to know what my credentials were, if we could keep a copy of them in the office just in case. Just in case of what? Oh, and he wanted to look into offering an additional certification of some kind in the class. I told him I’m not interested in offering an extra certification: my students through the years have put this course on their CVs to good effect, and I’m not equipped to certify anyone. I wouldn’t want to, anyway, from the organization I first learned from, as they’ve got a terrible reputation among film sets, and I myself grew to resent their exclusivity and their old-boys-club attitude. As for my worthiness to teach the class, whoa. Where did this questioning suddenly come from? Did he need another copy of my resumé, so he could be reminded of my vast experience, spanning time since 1996? He’s known me since back then–surely not. Surely he didn’t question the chair before him, who hired me specifically for this—she’d seemed to think my credentials and expertise were more than sufficient, and they’d only gotten better since. Between this, the stipends, and Bubbles, I felt the shouldering out, hard, and saw the writing on the wall.

Bubbles has certification powers, too. I was suddenly not the only faculty there who knows this stuff anymore. As an affiliate, I was not allowed to direct productions for the university, either, and Bubbles doesn’t need me for fight choreography. I was the expendable one, seventeen years of skilled and faithful service absolutely notwithstanding. And she is good, it’s not like she’s not—she’s doing a stellar job to this day of decolonizing the Intro to Theatre class, making it cover more diverse ways of doing theatre and replacing the old textbooks with open source (read: free) books instead. It’s good work and it needs doing, and I honestly wouldn’t know how to do those things, myself.

I am glad I still was able to keep adjuncting through the pandemic, when so many others lost their jobs, especially those in the performing arts. It feels a little gross, to be thankful for an abusive situation, but it’s a weird and uncomfortable truth. I keep being assigned some classes each quartter over at DU, though sometimes I have to put on puppy eyes if they don’t assign me courses right away, and then they usually come around if they can. I know I can't rely on this cute-pet-like begging, though, and the stress I fall under during each transitional period between class sessions is becoming too hard on my health.

This intense stress comes in two waves: the first wave happens usually around mid-semester, when I find out if and what course/s I’ve been assigned. Not knowing how many (and if any) sources of income I’ll be getting for the next four months makes my life both impossible to plan for as well as unstable in the extreme. When applying for a loan or for financial assistance programs, this instability makes it difficult for me to give an accurate statement of income. When the range is literally $0-$2000/month, there’s not a whole lot that anyone can do. For the two months out of the year I don’t get paid, too, I can’t apply for unemployment. Because I am employed. Just not paid.

The second and more intense wave of stress comes between 1-3 weeks before the classes I’ve signed up to teach are scheduled to start. If enrollments are low, my course can be canceled. If my classes are fine but any full time tenured professors’ courses are low enough enrolled to be canceled, my course can be yanked out from under me and given to them. This, at such short notice, means I may already have built full syllabi and online course shells full of 16 weeks’ worth of material, all for no pay. And at that point, I’ve certainly counted on having that meager income for the next four months. And I probably don’t need to explain that finding a replacement for that income is pretty much impossible at that short notice, certainly so in academia, which is at the moment the only job I’m really qualified for.

Add to these regular stressors the new potentially lethal one of pandemic regulations and restrictions and risk, let alone the lower enrollment which is but one of many symptoms of academic plague life, and it’s no surprise I’m burning out every few weeks now. An online friend once asked me how I do it. I have no idea, I told her. She commented that I must have a great therapist, at which I laughed—I can’t afford a therapist, are you crazy? She replied, not laughing at all: Are you crazy?

Gaslighting doesn’t just include the mind-fuckery that the narcissist inflicts on their victim during the relationship. It remains potent way beyond separation from the abusive relationship. The gaslighted victim, reeling, will often react to their messed-up perspective by blaming themselves for the bad end, blaming themselves for the pain of the relationship itself, even for explicit abuse. It’s a “look what I made them do to me” syndrome that stems from the abuser having messed with their victim’s sense of self so completely. A survivor may not know who they are anymore, and, trauma-stricken, may have an incomplete or warped memory of the kinds of abuse they suffered.

Shahida Arabi, in Power, lays out several tactics malignant narcissists employ to keep their victims captive. A few of these tactics occur during the relationship itself, but one of the scariest modes of narcissistic gaslighting happens after the victim has finally escaped their abuser. That insidious tactic Arabi calls “hoovering.” It’s called this because it resembles the suction of a vacuum cleaner, irresistibly drawing the victim back into the relationship. The abuser sucks their victim back in with honeyed promises of change, of operatic declarations of regret, of missing the victim, and even faux-pathetic wails on the how-could-you-do-this-to-me theme.

They don’t hoover because they sincerely miss their victim who has escaped their gaslighting clutches, but,

“because they want to ‘con’ them back into the abuse cycle and test how far they can trample on their victim’s boundaries once more. In the abuser’s sick mind, this boundary testing serves as a punishment for standing up to the abuse and also for going back to it” (emphasis my own).3

Arabi prescribes going strict No Contact with an abuser, to assuage the effects of hoovering. If No Contact is not an option, she suggests going as low contact as can possibly be done. If, for example, you have had children with your abuser, you’re going to have to have some kind of contact with them. In that case, it becomes even more important to set strict boundaries, or you could get hoovered easily for the sake of the innocent lives involved.

When I first asked for a divorce from my gaslighting husband, I didn’t end up moving out for another three years after that. Why? A nasty thing called financial abuse. My income had been siphoned straight to him for several years at that point, and neither one of us had the couple grand necessary to get me (or him) the deposit and first month’s rent on a new place. Plus, my credit was dire, mainly from taking out shady loans to help float Ninjaboy’s cab driving job. We were behind in rent on our current place, and I think we weren’t evicted mainly because our landlord didn’t want to deal with us. Once he started to put the pressure on, though, finally, Ninjaboy forced me to call my parents and ask them to take out a loan on our behalf. These are two people who at the time were in their late 60s and still living in the trailer I grew up in, retired, and living on social security. They didn’t have any more money than we did, but they had good credit, so my husband thought they’d be willing to go into debt to bail us out.

I saw no alternative. Under pressure, I obeyed, in tears, and called my mom. Her response? She’d give me the couple thousand I needed to pay my share of the back rent and a deposit on a new place. My parents had just sold a small parcel of mountain land they owned, and was planning on saving the money as an inheritance. In that phone conversation, Mom heard my desperation, and saw clearly that my survival depended on getting away from Ninjaboy, and so she gave me my share of the inheritance early, to save me. She refused to pay a penny for my husband’s needs. It was: help only me, or no help at all. That was it—an ultimatum, but more importantly? An escape hatch. I agreed.

Ninjaboy, in rageful tears, declared that we were all out to get him. Inwardly, I countered to myself that he was a grown-ass man, and if he couldn’t hold down even a shitty job, that was not anyone’s fault but his. I didn’t say any of that aloud. It wouldn’t have done any good.

The only thing I said aloud was a tiny grain of that large truth—that this was my only choice. I let him cry. I left.

I would go out to coffee with Ninjaboy regularly as friends after I moved out. I can’t explain why. If I tried, I’d say that in my gaslit fog I was still under the “amicable split” illusion, still thinking with misguided cruel optimism that this was best, and a kind choice for both of us. Maybe part of it was guilt, or a sneaking suspicion that he was right about what I’d done to him by leaving. I held my ground with him much better than I had when we were still living together, but the effects of gaslighting were still fresh.

For example, I was still saddled with a negative bank account balance he had accrued under my name. It used to be a joint account, but I was the primary, and so I was forced to turn it into a loan and pay it off, which of course outraged Ninjaboy. I told him this at coffee once: I had no choice. Also, you owe me two hundred bucks a month, Ninjaboy. He was angry, but agreed. Two guesses how many payments I received from him. Of course he had helped me move, lifting many heavy boxes of books up three flights of stairs. I have no doubt that he planned to use that admittedly massive effort against me later in his litany of guilt trips, but I ended up going No Contact before he did so.

I probably would have kept attempting this awkward friendship effort, had my parents not gotten a call from some local police. There was a warrant out on Ninjaboy and they were looking for him. Mom called me about it, rather spooked, and that was the final straw. It was one thing for me to be feeling the repercussions of my relationship with him, but my poor, put-upon parents? They hadn’t made the mistake of marrying him, and they didn’t deserve any of his nonsense, especially the legal kind. I told my husband to cease all communication with anyone associated with me, and to only contact me if it was about a divorce hearing. He apologized and tried to hoover me back, again. I deleted him from all my contacts, and blocked him from all communication but email.

He went on to get evicted from our old place, lost everything he/we owned, sent our three innocent cats back to the pound, and proceeded to attempt to be a parasite to two different old friends of ours, one after the other, as roommate/mooch. Funny, that—when he and I first met at RenFaire, he was living on a mattress in the common room of a couple of his friends. After an ugly divorce. Yes, it sounds familiar. Now it does, at least—I didn’t heed those red flags at 25 years old. Didn’t know how to see them, back then. I’d believed him, when he’d said it wasn’t his fault. I gave him a chance. And another. And another…and, after 20 years of my patience and perseverance, he finally ran out of chances. No more Next Time for Ninjaboy.

Last I heard, he changed his name to a New Agey yogic themed thing, no doubt as much to evade the police as to echo his own mystical interests. And he hosts a YouTube page centered around conspiracy theories. It’s the kind of train wreck that’s hard to look away from, though I’m doing my best…

I read several articles, particularly during the worst of the COVID lockdowns, relating studies showing that the pandemic made this abusive/possessive/isolation dynamic much worse for many victims—locked down with their abusers without the money to escape. “COVID doesn’t make an abuser … but COVID exacerbates it. It gives them more tools, more chances to control you. The abuser says, ‘You can’t go out; you’re not going anywhere,’ and the government is also saying, ‘You have to stay in.’”4

A trapped and gaslighted victim will often talk herself into a fully different story of her pain than what it really is, daily, just to survive, and because her perspective of reality has been so messed up that she often can’t clearly see the abuse for what it is. Plus, in a pandemic? Where’s she going to go?

At the time I quit Subway U., I had over a hundred thousand dollars of student loan debt accrued, because of the state of my job’s horrid pay (working in my degrees’ field, let’s not forget), plus interest over close to twenty years of very sporadic payments, if any. My career has basically been two decades of Financial Hardship forebearances. And the public service loan forgiveness program? Nope. I don’t qualify.5

Should I just leave, the way I left my husband, and get a new job? Sure. What job? Where? I am a woman in her fifties, and my job experience? Twenty-two years in academia. Okay, yeah, I worked some shitty retail and administrative jobs before I got into academia, hoping I’d be promoted at least once in twenty years. Bartenders and servers both would be a better living than mine, but I have zero experience in those jobs, wouldn’t have the stamina for them at my age, and both of those jobs are highly competitive where I live, and rightly so. Go for an entry level corporate job? Right. Borrow more money for another terminal degree in the humanities? Go get an MBA? With more debt? No way.

I have been doing a good amount of freelancing (been doing this for years actually), both in the writing and theatrical fields. But that income is even more paltry and unreliable than adjuncting, if that can be imagined. And there is the little matter of a pandemic and post-pandemic world. So many of my theatre colleagues got canned during the worst of it, and many academics too. I’ve been facing the odd reality that my shitty, abusive job is actually better than most situations right now. It’s a sad contrast: at the beginning of my career, I stayed adjuncting in the hope it would get me a better job; now at the end, I stay because it’s better than no job at all. Though I’m starting to wonder: is it?

Have I been hoovered? No, not really: for one thing, I never actually left adjuncting the way I did my marriage and the theatre. Also, I’m seeing reality not through the dimmed, Vaseline-smudged lens of the gaslighted, but for what it really is. I’m not being pessimistic nor masochistic about adjuncting, only realistic. And now I’m putting my voice forward a lot more: Right before leaving Subway University, I was a member of its Faculty Senate, and Faculty Welfare subcommittee, which in the grand scheme of things didn’t do me any immediate good, but I did learn about the tedious and seedy underbelly of how things actually work in the university system and so …who knows how I’ll be able to leverage that knowledge in the future. Maybe a union that actually works this time? Maybe some more money?6

And I’m regularly sharing articles aplenty about the adjunct plight—I’m making the real national (even global) situation well known to those couple thousands in my social media’s captive audience and, while these complaints might get me in trouble at some point, right now I am still getting at least verbal support. I don’t feel like such sharing of facts will cause me to be out of a job, but of course I never know. It might.

I wriggled out of the abusive theatre trap a few years ago, and, though I was hoovered back in a couple times via ego-stroking, I overall was successful in taking my poor exhausted self out of the pool of sacrificial talent by setting clear boundaries and, more importantly, adhering strictly to them. These boundaries consist of three rules, and every role I audition for must include at least two of the three, or I won’t bother:

The role must pay

It must be very large, or otherwise important (like a dream role or lead)

It must not require me to give up inordinate amounts of my time/life

What this self-discipline has done is loosen a stranglehold on my life that had been squeezing the lifeforce out of me since teenhood. It means I get hired to do a lot of fight choreography. I haven’t even appeared onstage any less often than before, really, it’s just that when I do, it’s worth my while and my resumé. I’m doing theatre on my own terms.

Since laying down this law for myself, beyond multiple good fight direction gigs, I’ve appeared in:

-two iterations of devised theatre piece I Miss My MTV;

-a pivotal role in a Sherlock Holmes play;

-storytelling for two different online showcases, one of which was a dramatic reading of Poe’s “The Raven”;

-a poetry reading with a punk rock band accompanying my original work;

-an old singing role and an MC for two benefit performances produced by the old aerial dance group I used to be in;

-three fun Shakespearean bit parts for a friend’s Zoom theatre festival during the worst of COVID;7

-a full virtual reenactment of gruesome Jacobean drama The Changeling, recast from all the actors who originally did it together in 1995 as students at CU Boulder. The director even came back to witness our revamping of the old piece he’d directed and we moved him to tears;

-playing dream role Feste in Twelfth Night, up in Washington State, an experience I would never have been allowed to pursue in my previous abused life.

I was hoovered a couple times during these years of liberation though—my break from unimportant or unpaid acting wasn’t perfectly clean. After the Sherlock play, that same community theatre company hoovered me back into doing a musical with them. Which, to be fair, was a very big and multiple-role gig, but the company and the process was so unpleasant, and took up too much of my life in the rehearsal process for not-so-glorious results. We had no real music director, only an accompanist who played a version of the music that was quite unlike the Broadway discs or accompaniment recordings we’d been given to practice with on our own. The director was flustered and domineering, causing a handful of cast members to drop out of the production, while the rest of us stayed, frustrated. My husband was cast, too, and arrived almost too drunk to perform half the time, and once actually was: he was forbidden from entering the stage at all because he was too far gone to do his parts. That wasn’t the theatre’s fault, but when they didn’t fire him after that, my doubts as to their professionalism spiked to a new high. Were they that desperate for male actors? I left that company for good, and have only gone back to choreograph fights for them once in a while when they really need it. The role that pays.

Before I moved out of Ninjaboy’s place, he’d gotten an agent and was auditioning for a few things pretty frequently, which threw something of a wrench in my discipline machine, as far as theatre hoovering me back in. I followed him into one audition, only meaning to be a reading partner for his own tryout, and ended up getting cast in it myself. Doing the fight scenes for that show was fine, but I really shouldn’t have done the acting role, though of course I was great in it. That was only one other brief weakness, though, and for the most part I was able to be very select about what I performed in, and stuck to my rules. Till I got into (and then out of, and then hoovered by) that notorious Boulder burlesque troupe.

“Ssh! You guys shut up, I want to hear their story!”

“Okay seriously, come on: tell us what happened!”

We were a spangled, shining group of about 7 performers of any age and gender imaginable. A ballroom dancer turned burlesquer, an outside the box performer who did something called reverse burlesque, an intersex drag artist, an opera singer and cosplayer, and more, besides me and Brandy, who are the co-founders of Blue Dime Cabaret. It had been the 4th or 5th gleeful, tipsy interruption, but none of us were really worried about it. We were warmly enjoying each other’s company—a respectful, even caring, camaraderie. None of us were in a hurry.

We were crammed around the small conference table in the break room of a quirky little office space called the Candy Shop. Brandy is CEO of her architecture firm, so a bunch of the troupe were meeting here in her company’s space, to toast the success of our first independent show and Fringe Festival week, and to scheme for the next phase of our “lowbrow, avant-garde variety show” that had gained such momentum just within those first few performances.

We also had just heard the final message from the other burlesque troupe; the conclusion to a back-and-forth conflict that had begun with a cease and desist, and ending today with us being kicked out of their toxic troupe officially, once and for all. The final Next Time had expired.

We had laughingly announced this fact at the beginning of the Blue Dime Cabaret meeting, showing how we were weeping crocodile tears into our wine, and the group of beautiful Dime pieces demanded to hear how it went down. Brandy and I were so punch (and other kinds of) drunk that we made the mistake of putting Jenn Zuko in the spotlight, to take focus and to narrate the story of How We Broke Up With That Other Troupe. To say that I milked it would be a wild understatement. As I say to this day to Blue Dime audiences: Never hand an actor a microphone.

See, what happened was… wait, a bit of backstory first.

I had been corralled into being the main coordinator/organizer for the Boulder troupe’s big Fringe Festival series of shows: 7 shows, each one with a different lineup. The Fringe Fest is a big event in Boulder, with an international smorgasbord of performances, bigtime reputation, and full audiences, and I’ve even heard it’s one of the biggest Fringes outside of the OG one in Edinburgh. I’m an experienced theatre professional, unlike any of the rest of that troupe was, and so I was the only one capable of pulling off organizing such a production. This was towards the end of my run with them and so the fucks I had left to give were down to nearly nil, but even so I was still amazed at the backstage climate. The level of cattiness, diva backstabbing, and the insufferable neediness of Madame Malbec in the center of the whirlwind made the whole situation unbearable—this act dropped out last minute, that other one had a huge fight with MM because of a perceived slight, then that act’s wife also dropped out because of the insult…. just. The childish level of unhinged bitchiness was off the charts and I had no idea whatsoever how they ever had gotten anything done without me.

Suffice to say that they soon were forced to do so again—I handed in my resignation after that Fringe experience. Two hundred bucks was not nearly enough compensation for the amount of emotional and other labor the event had siphoned from me. I performed with another, smaller local group for a bit until that one also imploded from divalike disaster. That’s where I met Brandy. A calm, beautiful, confident woman just a little older than me, she’d gone through the Boulder burlesque group’s robbery of a workshop, had a disappointing and stressful couple of performances for them, then found her way into another smaller troupe, where we both commiserated about our experiences.

I did get hoovered one last time by Madame Malbec’s sweet compliments, begging me to come back and choreograph a group piece for the recent suckers—er, new dancers who were concluding their overpriced workshop. I did so—and was very pleased with how my group piece was performed by the burlesque babies. I also performed an act of my own. I got paid my eighty bucks, but the whole scene was just as syrupy and corrupt as before, so I left them again, this time for good.

Both of us now bereft of a place to happily burlesque, Brandy turned to me and asked, “Hey, want to start our own group?”

Fast forward to our own Blue Dime success at the following Fringe Fest—a totally professional, smooth, and brilliant production, of course, in contrast with the other troupe’s debacle. Then came an email that Brandy and I both received. This is what I was trying to tipsily relate, in between giggles and sips:

So it seemed that one of the performers who danced for us, who was also a new dancer for the Boulder troupe, used a photo of herself for our promotional materials that was taken at one of her performances with them. Madame Malbec demanded that we take down the picture from all promotions, as it was proprietary to her troupe. That they legally owned it.

Thing is, that picture was of a dancer performing her own choreography, to a famous song, and was snapped on a phone by her friend in the audience. In no way did they own any of what that picture was. Not their dance, not their music, not their venue, not their photographer even. It happened to be at one of their shows. We told them: oh okay well if this bothers you we’ll tell future peeps to not use pics from your shows, but. Yeah no, we’re leaving that one up and you can politely bugger off. The dancer can do what she likes with her own images.

After a little back and forth, where they blustered and tried to get legally threatening, to which we laughed, till this last email from them, which was basically the following: we love that you’re another successful local group (yeah I bet you do), but because of this irreconcilable difference (oh jeez give me a break), we will welcome you to come to our shows as audience members (and I bet I have to buy a full price ticket), and we will encourage attendance at your shows (sure you will), but we will no longer be asking you to perform for us, or choreograph for our shows.

Boo hoo hoo! Brandy and I both cried, as the Blue Dime listeners crowed, aghast at their gall. “Are they just jealous?” one of them asked. Our happily mocking toasts to their and our health answered that.

But one thing’s for sure, new as we were to the scene, we were casting a bright blue shadow that the other narcissist-led group was already getting lost in. And for me individually? I’m feeling the power of producing—now I’m giving myself the performances I deserve, both in casting myself and in choreographing and designing my own pieces. The confidence in my body’s beauty I’ve gained in this practice has also led to a modeling hobby. I can’t say that a lifetime of negative influence has fully been cured, but I’ve come a long way, baby.

Blue Dime Cabaret has gone on to produce a new brilliant show with more brilliant artists of all brilliant kinds, about once a month, sometimes more, at a Boulder bar with standing room only, at a Denver theatre that moonlights as a BDSM dungeon, and a couple times up at an extraordinary Wild West era saloon up in the casino town of Central City. We only stopped because the 2020 pandemic wouldn’t allow our packed audiences and tiny dressing rooms. We started up again as soon as it was deemed safe to do so, and immediately sold out a local theatre…

Not a perfectly happy ending to this story (no life story’s end can be, of course, and this isn’t the end), but now that I’ve taken these painful and difficult steps, it’s so very much better. I’m still doing the things I love and am excellent at; the difference is, I’m in charge. Well, mostly. At least I’m not putting myself on hold for Next Time.

That’s really the secret: Psychologist Henry Cloud nails it, even though he doesn’t speak specifically about gaslighting, in Necessary Endings:

“If you are looking for the formula that can get you motivated and fearless, here it is: what is not working is not going to magically begin working. If something isn’t working, you must admit that what you are doing to get it to work is hopeless.”8

Hope is not always a good thing—sometimes, it’s much healthier to be hopeless. And to specifically, precisely, hate. Just a bit. In exactly the right places. It gives you a spine.

At five decades old, now I am finally the one making my own life choices. As I resume the career change labors that I had stopped during the worst of the pandemic, I’m continuously reminded of the influence I’ve had on the many students I’ve impacted for so many years. I hear from them a lot: how I still influence them, not only with the material I showed and shared with them while they were in my classes, but by personal example—by simply being me.9 Many of my former students come back to perform all kinds of awesomeness in my Blue Dime shows. They tell me tales of the glorious directions their own careers have gone, too, and how the skills I taught them are still helping them every day. And one of those former students? Up until a couple months ago, he was the poet laureate of Colorado.

And of course, for now, many students still flow in and out of my influence. So, this is how it feels. And we’ll see what unfolds from here. There’s a lot of possibility ahead. Lots of hard work. Lots of healing, and re-training my brain. But I’m not in the dark anymore. I’m learning how to cultivate a healthy hopelessness, a positive pessimism, and stronger boundaries to keep at bay those who would take advantage of me or abuse me. I no longer stay in toxic situations. I clear the poison, or I clear out. I’ve turned up the light.

Myself? Let me tell you about myself. Pull up a chair.

~

As of my checking the stats on CollegeFactual.com Oct. 6, 2021. I didn’t check the DU adjunct percentages (the university where I still work now), because I know for a fact that the department for which I teach only employs adjuncts for all their faculty needs.

Answer: chopped liver, I assume.

Arabi, Shahida. Power. Thought Catalog Books, 2017. p.63.

Kluger, Jeffrey. “Domestic Violence is a Pandemic Within the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Time, Feb. 2021.

I am very happy to report that, a while after this memoir was finished and polished, I was one of the first recipients of the Universal Student Loan Forgiveness sweeps done by the Biden administration. Which doesn’t mean I magically have good income, but. Hoo boy , is it a load off.

And bingo: the faculty welfare subcommittee wrangled a grand per semester for affiliates serving on Faculty Senate. And I reaped that reward for my final semester of service. Too bad it wasn’t grandfathered: I served a total of four semesters on Faculty Senate.

I’ve actually continued to be an active part of Covid Shakespeare Club, and have played so many fun wonderful parts of all sizes that I’d never have been cast in normally.

Cloud, Henry. Necessary Endings. HarperCollins Books, 2010. p.74.

Former student Andrea commented this on one of my social media posts about teaching: “Omg Jenn Zuko I want to be you when I grow up. Just gotta sing your praises too because you’re the fucking BEST. Like, the realest of the real. The most authentic human. I just think you’re such a badass and I’m so lucky to have had you as a teacher. You’re a badass lady and it’s nice to have badass ladies to look up to.” I reread this whenever I feel underappreciated.