Next Time

4 Landscape of the Body

About that one time I chose Porn Star over Irish Matron, and what happens when a gaslighting victim finally rocks the boat. Also, Talented and Gifted is a deceptive label, which makes a person too susceptible to the wiles of a narcissist. The insidiousness of typecasting is discussed, and how polyamory saved my sanity.

Chapter 4

Landscape of the Body

Being an actor, especially a woman, especially when large and not traditionally beautiful, is a constant striving for a fictional Next Time. Being cast for traditional beauty or a small dress size is stark reality—it usually doesn’t matter one whit how talented or skilled an actor is. Most of the time, her talent has nothing to do with whether or how well she gets cast.

That a person is given praise, accolades, and success in life for and according to one’s talents is a cherished myth that I couldn’t convince my mother to give up, try as I might. The cluster of promises given to children in Talented and Gifted programs may be one of the deeper and more dangerous lies around, and it takes a long time to shake off the attachment to this particular fiction, to stop looking for a Next Time that doesn’t exist.

My mother, a dance education major when she got pregnant with me, is a firm proponent of the innate talent myth. As I was a freakishly early reader, and a supernaturally talented dancer, she had what she felt was proof that genius and talent is all nature, not really nurture at all. She, Columbo-like, would always self-deprecate, describing her own skills as no big deal: “I was never a very good dancer,” she’d say. “I had to work twice as hard as the talented ones in order to keep up. So my technique is okay, but I’m not as good as the talented ones.”

Technique, she’d tell me, is always learnable. Anyone can work hard and get good technique, but it’s those rare few that are actually talented that are the truly good and therefore successful dancers. Same with intellectual prowess–since I learned to read at just about two years old, I was a natural genius. Her hard work at gaining a Masters degree in Whole Language Education, her immense skill as a teacher, wasn’t about talent--it was only the hard work of a peasant; a grind, nothing more. My innate intelligence, unlike her hard work, was something special.

Yes, I am quite talented. I am also highly intelligent, and am very, very good at what I do. At all the things I do. But I learned late in life that, actually?

None of that matters.

I don’t say that with any kind of sorrow or rancor, either--it’s just the way the world works. Being raised in the Talented and Gifted program, being told I was some kind of amazing prodigy as I grew up, was damaging. I wasn’t expecting the real world to look me in the not-very-pretty face and tell me that my amazing-ness kinda wasn’t.

I’ve since learned, from my partner who’s a parent and who underwent similar Talented & Gifted damage as a kid himself, that the thing to say to a talented child is not, “You’re so smart,” but “You’re working so diligently,” or, “Wow, what an improvement--I can tell you’ve been practicing.”

Because, unlike what my mom thinks is true--that’s what talent is. It’s work. It’s practice. I learned to read early because my mom was at home with me, encouraging me, reading to me, taking me to the library, showing me episodes of Sesame Street and Electric Company, and in a myriad other ways basically teaching me to read. I didn’t just magically start reading out of nowhere. I am a talented dancer because I’ve been doing it all my life--literally since before I was born. There is no such thing as magical, innate genius: Mozart wasn’t Mozart in a vacuum--his father created the environment where his talents were able to flourish. So many other incredible geniuses through history show this. Not to say that nature has zero to do with a person’s talent, but if one looks at what happens to a person with all one as opposed to all the other, it soon becomes plain that nurture, environment, education, whatever we want to call it, is essential.

Mom denigrating her own talent by labeling it not as talent but as “merely” hard work is a foolish falsehood to grow up with. Feeling like you’re special, too, leaves you susceptible to the grasping claws of a narcissist. If you’re already convinced you’re extraordinary, you’re not only blind, but wide open to that first phase of the narcissist trap: the over-the-top, insincere admiration dump. You let yourself get put up on a pedestal because you’ve grown up thinking you deserve to be up there. By the time you notice that you’re chained to it and can’t get down, it’s far too late.

So what if I’m talented?--those seventy five women at the audition who look just like me except skinnier and prettier are also talented. Or maybe they’re not, but they’ll still get the part, not me. They’ll get it for any number of reasons besides talent, most of the time: This woman got the big leading part because she’s a friend of the director; this other one because she’s shorter than the male lead. This one here can’t act her way out of a paper bag with Shakespeare written on the outside, but she wears a size 6 dress, so she’s going to get the part. They already spent the money on it, after all.

Is this unfair? I don’t know if it is, actually. It sure feels like it if one’s drunk on the Talented & Gifted koolaid, though.

“But honey, you’re so much better than her!” Yeah, I am. But that doesn’t actually matter, Mom.

“Well, you’ll get it next time.”

Sure. Next Time…

The powers that be at the theatre department at my undergrad university were highly irked when I took an actual, real-life Next Time into my own hands late in my senior year. It was the second to last semester of my BFA in Acting, a rigorous training program touted as better than many Masters degrees. As such, I was required to audition for each play they produced, both for audition practice, and for the acting experience of whatever roles I’d get cast in. If any. Thing is, I had been getting a certain type of role, based mostly on my looks. I’d be turned down for several other roles, too, for the same reason. This, in the biz, is called “typecasting,” and as my undergrad program is within a school, and was supposed to be educating us and training our beginner-level skills, they claimed they never typecast. They’d acknowledge that typecasting happens all the time in the professional world, and that in order to give their students the experience they need and deserve before graduating into it, they’d choose unusual plays and never typecast or pre-cast (putting students in a role before or without needing to audition).

Several old lady neighbors and saucy maids and sometimes no role at all later, I began to doubt this claim. I noticed, too, that the same classically pretty girl kept getting all the female leads. I wouldn’t have been surprised by this if it hadn’t been a school, but they were so vehement about their proclaimed equity. However, the university plays did get reviewed by local critics just like pro companies did, and they were usually up for the same local awards. Did this mean my school was casting as though they were a repertory company and not an educational institution? Surely not.

The fact that I was so gullible as to have believed their casting nonsense for the first couple years of my college career is another sign of my trauma-bonding reaction to my earlier life in the theatre. I mean, I went to college directly after high school--in other words, the Dolly Dress Debacle hadn’t been that long ago. Had I forgotten all of that? No, definitely not. But that was high school, and junior high before that. It wasn’t a prestigious BFA, a professional training program, at a well known university for same. This, surely, was different. I believed the current abuser in charge when they gaslighted me. It was the fictional Next Time syndrome yet again: this time it’ll be better. This time, they mean it when they tell me I’m good enough. This abuser won’t lie to me like the other one did. This time, they’re sincere...

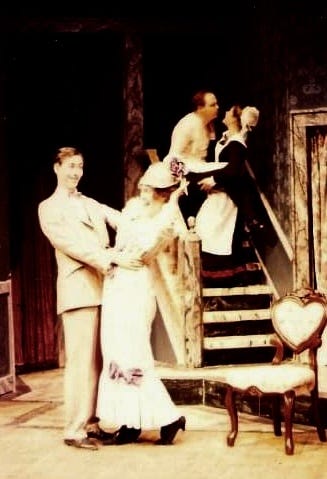

This penultimate semester, I decided to do something different, to take my education and my CV into my own hands. A graduate student I knew was putting on a professional production of Landscape of the Body at a local theatre and wanted me to take on a large lead. This was a much different type of part than I’d regularly been getting at school, and looked challenging—it involved narration, breaking the fourth wall, and several songs. The play is a bizarrely surreal John Guare piece, centering around the death of a teenager and the life of his mother, presented in fragmented flashbacks including narrative songs, a harsh detective, a man in a gold dress, a severed head, some beautifully poetic monologues... and the whole thing is, cabaret-like, narrated by a dead porn star. This last part was offered to me. The director said I was the only one he knew who could pull this difficult role off--I had the required skill set and the ability to tackle a role of that large size.

I mean, holy cow; that sounded great! Finally a part that my weird and wide talent deserved. And I’d get to be pretty! One big obstacle stood in my way--we weren’t allowed to do any shows outside of school productions whilst enrolled in the BFA program. Something about not wanting to taint our training with work that’s done in a different way. At least that was the claim. Morosely, I poised myself to turn down this exciting, strange, professional play for the one I was required to audition for at school. But when I saw what part in what school play I’d be refusing to audition for in favor of this? I decided to break that rule. The school play was Irish drama Dancing at Lughnasa. The role? The oldest sister--mother figure for the rest of the characters. At the time, especially when compared to the glitzy, bloody, and oddly dark Landscape, Dancing just sounded dreary, dull, and depressing. And to play yet another poignant Someone’s Mom? No thank you. I was 22 years old--I was sick of old lady neighbors, mothers, and maids. I was tired of painting lines on my face. I was sick of grey hair color--this new part would require me to dye my hair bright red.

I took the Landscape role gladly, university policies and rules be darned. And anyway, it was only an audition for the sad grey part--what if I didn’t end up getting cast? The spectacular, singing, lingerie-wearing, sparkly dead narrator character was a sure thing. It really wasn’t a choice, once I thought about it.

The department’s reaction to me taking a professional role over their typical part they’d expected me to fill was similar to that of an abusive partner when his victim calls him out, or stands up for herself. I explained the situation, the role, the choice I had made and why. Their initial reaction was to play the classic narcissist’s how-could-you-do-this-to-me card. When I wouldn’t budge, they switched to veiled threats: I wasn’t supposed to break out of school and do community theatre; it’s a bad influence on the training they were providing for me, this might affect my castability later, in my last semester…

Well, I figured, if I can get cast outside of school, in big professional parts, and if the only parts school is willing to give me are old ladies and maids, then gee, maybe not being cast by school anymore ain’t the devastating thing they’re trying to convince me it is...

I knew this was the right choice, and that bowing to their harsh and what felt like arbitrary rules would undercut my growth as a performer.

I shone as this new challenging part, in Landscape. I got great reviews from the local theatre critics who touted me as a highlight of the show, and I learned a lot in this part that stretched me to my limits. The department did end up making an exception to the no-pro rule for me, since the director was one of their own grad students. They cast a very lovely and talented junior in what would have been my part, and she did a great job.

This was a bold move, and I really did think I’d be sacrificing all my other potential school roles to do it. Abusers make it clear: standing up for your own needs gets you punished. Or so you’re told, over and over, till you test that threat. Turning up the gaslight and taking a stand for what’s best for you can render the narcissist powerless. Not always, and that’s not always the only thing that’s keeping a victim captive, but it certainly helps. It helps illuminate what’s actual reality, and what’s the fabricated false reality the narcissist needs to cultivate to keep you in, to keep you under their sway.

Part of why I was able to take a stand in college, I think, is that I did a very similar thing during my junior year of high school. Almost the same sequence of events, and with a similar end result.

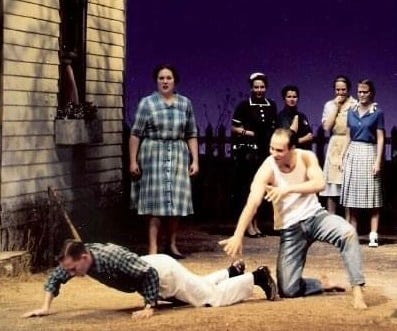

It was junior year, and the play was elaborate, complicated, and challenging farce Noises Off. My reason for not auditioning for the big lead role wasn’t another better professional part this time, but was for an equally important reason for my future growth as an actor: As an 11th grader, I needed to spend those months not in rehearsals, but filling out college applications, grant and scholarship forms, and studying for the big standardized tests that would dictate where I could even go for college. Sure, the play would’ve been awesome, I would’ve been brilliant in it, and it would’ve been a blast. Several of my good friends were in it. But I refused, choosing my future over my immediate present.

The director was aghast at hearing I wasn’t auditioning—who else, she almost angrily demanded, could she possibly cast in this part? I was the only one talented enough to pull it off! In fact, she chose the play specifically because she knew she could cast me.

Sorry, I guiltily told her: I can’t afford college at all unless I do these things now. She was distraught, and came this close to accusing me of making her production a bad one on purpose, by not taking the role she had expected me to audition for.1 I still refused.

She ended up casting a slightly younger girl in the part, who did just great. She was sort of the up-and-coming me, or the off-brand me, at that school. She had a similar older manner and look, was similarly large, a decent actor that I had actually appeared with in junior high. She was perfectly fine. She just wasn’t quite the absolute star I was at that school, at that time. When I graduated? In other words, I wasn’t the only one that could possibly do that part. And I got a full ride scholarship to the school of my choice, for the first whole year of college plus room and board. Got a decently high test score too. Letting that other girl take “my” part was absolutely worth it.

Me throwing the wrench into that college theatre department’s abusive machine made it obvious that they had indeed pre-cast me for the role in Dancing, even if they didn’t admit it the way my high school director had. I noticed how they panicked when I refused to audition--obviously they were counting on casting me in the typical old lady/mom role they’d been doing since I arrived into the program. Since I’d been doing since I was 13, when I first entered the theatre arts, and had to spray that grey stuff into my hair for the first of countless times. I can still see what the silver spray can looked like, and can smell that sweet, powdery scent that the grey color in particular had...

They were regularly relying on me for filling these parts, though they repeatedly denied it. This time, I refused to go along with their unwritten rules and made them scramble. It didn’t stop them from the behavior, but I like to hope that it made them think twice.

Nah, they’d just write it off as That Eccentric Zuko. No wonder she’s so hard to cast.

During my marriage, my husband relied on me to give him all my money to “manage for the household.” Ostensibly, it was set up as a household pool: he’d put all his income into the maintenance of the house and so would I. And then he’d be the one in charge of dispersing it all: he claimed to be better at money management than I was, and, to be fair, I was awful with my meager income at that time, so I was content to let the man I married take on that responsibility. By the time our marriage was ending, he wasn’t making any money himself, though, so all our finances ended up all on me, though he still took it and managed it all. More than once, I went entire months without feminine hygiene products. One Colorado winter, I had neither a winter coat nor snow ready boots, though my husband had two sets. I believed him when he said we couldn’t afford these things for me.

Up to a point: late in our marriage, when the end was visibly near, we decided to open our marriage.2 Once we did this, I began to experience the generosity of other people besides my narcissist husband dating me, paying attention to me, and being interested in the things I did and who I was, and my immense talents, and….

One of these whom I had been seeing for a good while, sat down with me at one point and asked the potentially victim-blaming question of codependency, which was in truth a wake-up call for a woman he knew to be strong and intelligent. He asked, point-blank, why I, a strong, badass, and talented woman, was letting my husband do this to me.

“He doesn’t treat you well,” my boyfriend said.

“I know…” I replied.

“You know?! Are you hearing yourself?”

“I—yeah.”

“I would treat you well.”

“You do!”

“Why do you let him treat you like this? Why do you stay with him?”

I had no answer to those questions, except to repeat them to myself. I wasn’t growing artistically or personally, wasn’t being fed, clothed, or in fact getting anything out of my sacrifice. Was I even loved? My husband and I hadn’t touched each other in months, or was it years... That’s when I chose to ask for a divorce.

Of course, my husband acted affronted, as if I were out to get him, or wanted to make him fail on purpose, or that the other man stole me away.3 Once I, the host, stopped giving him everything, he, the parasite, had nothing left. Later, once I left that household and quit giving him money? He lost more than one job, as well as two separate friends who he tried to room with, kicked him out without much delay after he’d tried to mooch off them too. He threatened me with the lives of our three adorable, innocent cats—declared he’d not be able to keep them, would have to give them back to the shelter. Also that he’d probably kill himself. I had nightmares about those cats—I shudder to imagine what it would have been like if we’d had human children.

Narcissists keep their victims in the subservient part they need—if their victim breaks out of that, does anything more or, god forbid, moves on to different people and things that aren’t about them, they lose it and take it personally.

Sometimes the narcissist will easily replace you, like when I got fired from the adjunct position in the English department at Subway University—there were dozens of desperate academics flocking to my vacated post, clutching PhDs in their fists. Sometimes they’ll lure their victims back in when they try and leave, with praise and faux-humble begging, asserting that you’re irreplaceable, like my college theatre department did. Sometimes they implode completely like my husband when I left him--jobless and homeless and waist-deep in conspiracy theory, once I wasn’t there anymore to prop him up and pay him off. And the narcissist will always try and blame their victim, to make it not about their own continuous and/or systemic abuse, but about something, anything, you’ve done. Or about who you are.

A narcissist abuser will make it seem like your suffering under their abuse is your fault, and even potentially sympathetic outsiders will accuse a victim of codependency. Why not just get another, better, job? they’ll say about adjuncting. Why let theatre people abuse you? they’ll wonder about auditioning; just get a real job. And when it comes to a gaslighting husband? They’ll ask why you didn’t dump him and leave sooner. Wasn’t staying with him just enabling his abuse? Why did you let him do that to you?

This is the particular insidiousness of gaslighting: “When it comes to living in a perpetual war zone of intermittent kindness and chronic cruelty, there is no ‘enabling’ of the abuse, merely a need to survive in a hostile environment.”4 And this is what makes it so difficult to break free.

Not only did I blossom as the dead porn star in Landscape, but I made intimate new friends there from the professional theatre world, got cast at that same local company twice more in big parts in strange plays after graduating, and directed a show that was produced there. All much better things for me than one more mom or maid at CU would have been.

Oh, and my college did end up casting me again in a school production during my last semester, despite their threats. It was the ribald and rollicking farce A Flea in Her Ear, in which there were two female leads and one hefty female character part. The bigger lead was expected to go to the girl that got all the leads all the time, but I didn’t mind—that was the most boring out of the big parts anyway. The ones I was excited about, and up for, and auditioned for, and was best for, were two: 1) the second female lead, quirky and vivacious, who had a whole long sequence in which she spoke Spanish with her stereotypical Spaniard husband; 2) a voluptuous Italian wench, sensual wife to the manager of the Hotel Coq D’or, which would require an accent and a lot of purring sexual innuendo. Though I didn’t at that time have the curves for that second part, I had the maturity, brashness, and personality. I had the “oomph.” All this with the complicated language, difficult comedic timing, and precision in physical clowning that I was so good at, and that most of my fellow students fell short in.

Yep, they did cast me in that show.

As the maid.

AUTHOR NOTE: Man, I wish I had more pictures of Landscape, and even Flea. I lost so much of my own personal archive, including pictures, in the divorce. It’s really irksome. Yep, and the cats.

It was, though a large role, also an older lady and a maid. This typecasting of me had been going on since the very beginning.

Because when your marriage is going to pot, the best thing to do is to date other people, or better yet! include other people into your marriage in a polyamorous throuple situation. Because what could possibly go wrong…

The other man did not end up stealing me away: in fact, I refused his proposal of marriage, on the grounds that I did not want to fly from frying pan right into another frying pan. Turns out, I dodged another disastrous marriage bullet, but that’s a tale for another book. I’ll call it The Poly and the Polymath...

Arabi, Shahida. Power. Thought Catalog Books, 2017 (p.127).

Hello Jenn Zuko. I read your last three posts and I really like what you say (and how you say it). I could have commented on them all, but the subject is similar, so I can comment on all of them here.

Martha Nichols sent me; well, she recommended you, and I followed. Martha is probably looking at your writing expertise, while I am looking at your social commentary. (Actually you have stimulated me with tons of things to say, but I'll try to limit it with some focus.) I have become interested in theater only very-very late in life. In part, I lived where there wasn't any. And I have shunned movies and videos for many decades. But then this idea (below) came to me:

So often we define who-we-are by what we have done, our "Linked-In" profile. Our trail meandering through the past. Then I thought, but who we are is our range of self-expression in the present, (right now). Our past is a reservoir of self-expression to draw upon, but how are we using it right now?

That's when I thought an accomplished actor is a master of self-expression. Am I right or wrong? Maybe an actor is just confused, with so many roles rumbling through the corridors of the mind; What is authentic? So my intuition depends on the ability to choose. To choose the self-expression that is appropriate for my objectives in this moment. And that of course means that I can formulate an objective. (I CAN).

From that I would think you are a giant of a woman, with a giant range of self-expression.

The history of entertainment is that everyone was both a consumer and a performer. Grandpa had a fiddle, sonny a banjo, or back a little further they called it "chamber music". Now the corporate world has taken over entertainment. Someone will get a part in "the movies", but 100's of hopefuls will get your mythology of the "Next Time". Something is wrong with this picture.

Entertainers are part of our culture. Therefore cultured families will prod their children to develop these extroverted skills. Your mother said it, "hard work", (there is also talent, but that is a big discussion that I'll save for later). Aren't all top performers in the arts or in sports pushed by their parents? But the corporate is the valve (constriction point), where these performers are released into a meaningful job.

So it is out of balance. A million parents develop their children's skills, experience and talent, but only hundreds of them have a prospect to hit it big. That leads to a lot of miserable lives and a lot of abusive compromises. So in a sane world, a school for the performing arts would have a huge section about how to produce a new theatrical venue, how to wrest entertainment away from the limitations of Hollywood.

That presupposes that Americans want to see more original talent. I sincerely doubt it. Americans are content to spend their whole life on Youtube, and they will never run out. So is that what is left for you? You can make a Youtube clip, and hope that it is funny. It is the same as Hollywood isn't it? Five people get a million views and 5 million people made 70 cents on their last clip.

And Substack? I wouldn't read anything that I couldn't comment on.

.

Another great chapter, Jenn. I really like the way you connect typecasting in theater productions - even when those in charge insist they aren’t doing that (what a joke!) - to other forms of gaslighting. I can think of so many others in the elite literary world - Percival Everett’s “Erasure” (and the movie “American Fiction” based on it) makes clear how racial stereotypes drive expectations for writers - just one of many examples in which race and gender are routinely gaslighted by those in charge. You see it playing out now, too, in media assessments of Kamala Harris, and I speculate that she was routinely gaslit by Biden and his close male advisors - and still is.