Next Time

6 Flying and Falling

The art of aerial dance, in particular the one-point trapeze, is described as a metaphor for my gloriously skybound, yet inherently dangerous, way of life post-college. The ways in which ninjas (one in particular) are gifted in the crafts of infiltration and manipulation. Why flying feels so good, even though it draws blood, and bruises.

(NOTE: a clip of this chapter appeared in a Popination, at T Devon, wherein I discuss how I began smoking, and the correlation of pain and pleasure in aerial dance. Another small clip appeared in my vocab word essay about warriorship, Vapulate. ALSO: I have changed the names of individuals in this chapter, but not institutions, celebrities, or nicknames.)

Chapter 6

Flying and Falling

“You’ve got it! Trust it!”

Looking down from about ten feet up in the air, the petite instructor seemed quite a long way down, suddenly. I shifted my hands in the ropes, and felt all at once that I didn’t have a very good grip on them at all.

“You can do it! I’m right here! Trust me! Trust yourself!” she called up to me, tilting her face way up to let her voice carry that far, across the vast expanse of vertical space.

I had been taking aerial dance classes for almost two years at this point, and had been cast in the troupe’s upcoming show. The maneuver I was about to step into was an advanced one, but I had seen it done hundreds of times, had prepped for it several times myself, and knew in my conscious mind that it was fine, I was perfectly in place to execute it correctly, and I was certainly strong enough to handle it. But it felt different, difficult, somehow, now I was finally about to do it. I didn’t feel strong, or stable.

The move is called the Christ Hang, and it’s a beautiful position on the low-flying trapeze, one of my very favorites. How it works is: you stand on the bar of the trapeze, just like you might stand on a swing. The ropes, though, go behind the shoulders, from which you wind your forearms around the ropes behind, and then forward until your hands grip the ropes at the end of a spiral-like wrap. Then, you step back, off the trapeze bar, letting your feet float in midair and lifting the bar. You end up hanging in a harness of rope, wrapped under the shoulders and arms wide, looking kind of like a crucifix. If you’ve got a little upper body strength and don’t mind a little rope burn, it’s not a hard position to hold.

Thing is, before you take that step off the bar, your hands don’t feel like they have a very good grip. It’s because, before you take your body weight off that bar, they don’t. The ropes are too taut. Once you step off, the ropes give, and they cling perfectly around shoulders and arms to hold you up. But you can’t feel that when you’re still standing there, solid and safe.

I had taken one foot off the bar before in preparation for this move. I’d also done arguably more dangerous things on the trapeze: hanging by one elbow, wrapping my wrists in the ropes and hoisting myself upside down, tucking the bar under the small of my back and arching backward… but this particular advanced move did not feel nearly as reliable as any of those other things. And I was very high up. Back then, too, in the mid ‘90s, the dance company never used mats.1

“Trust yourself!” The petite instructor was down there spotting me, it’s true, but what exactly she could have done if my twice-her-size body were to fall, I wasn’t sure.

Only one thing to do: take that backward step of faith.

Though my parents never had much money to speak of, especially not anything extra, dance was a fundamentally important part of my life, because it had been my mother’s life focus for so long. Because of this, somehow she’d always come up with enough to pay for me to take one or at most two dance classes at the prestigious Colorado Dance Festival each summer. This festival was a very cool thing, and a big deal: it drew dance biggies from all over, which meant that between the ages of 14 and 16, I took several classes from stars in all kinds of movement arts. One year, it was Physical Comedy with none other than legendary modern clown Bill Irwin. I didn’t know who he was when I entered the class, only that I very much wanted to be a virtuoso clown myself. By the end of the intensive course, he was an idol and a highlight of my theatrical life still is from that class, when he and his partner-in-clown showed us some rough cuts of what would later be famous Broadway clown show, Fool Moon.

Another course I took at that time was called ‘Flying and Falling,’ which was all about learning lifts, other contact improv skills that used shared weight, and smooth transitions to the floor and to the air and back, by a troupe from San Francisco who were the first youngish artistic people I’d ever seen that were tattooed in elegant and subtle ways. I waited until 1996 (about 7 years later) to get my own first tattoo, but the deep desire began that summer. And when one of the lead instructors, a blond and tanned man, tall and leanly muscular like a soccer player, belly surfed across my logrolling body to demonstrate that a size or strength difference doesn’t always matter in flying or falling, I found myself viscerally ready to do whatever these beautiful creatures instructed.

That same summer was the first time I tried aerial dance. At that time it was mainly centered on the one-point, or low-flying, trapeze: that is, a long wooden bar about 5 or so feet off the ground, connected by long ropes to a high ceiling by one point. This makes the trapeze move in many interesting conical ways: sure, it’s possible to swing fast and high, but the spiraling that comes from the one fixed point also makes for some cool swirling paths through the air, and it’s possible to work simultaneously on the floor and up in the apparatus. I took the beginner intro intensive from local (nationally known) troupe Frequent Flyers, and though I didn’t come back to them as a regular student and then troupe member until I was in my 20s having just graduated from college, the softly floating art that yet left beautiful red marks, rope burns, and delicious bruises on my limbs stayed with me ever since that first summer. What can I say—in hindsight, that was the summer I discovered my kinks.

Here’s the part where I make subdued jokes about my preferences for pain included in my particular sexual tastes. These days I’d just cheekily call myself a Cenobite,2 but at that time in my life and artistic development I was so socially awkward and barely sexually active at all, so I can’t really call it that, except in retrospect. I had some dark desires but they didn’t manifest in the bedroom for me at all until my 40s. What was happening here in these twin extreme physical training tracks (the swords and the trapezes) was… I’m not sure, maybe it was training for my fetishes? Like boot camp or basic training before real combat? All I can say for sure is that the pairing of pleasure with pain was a daily discovery that I shared with all groups of athletes with whom I trained back then.

Just in aerial dance alone, there were regular and chronic injuries that were a normal part of becoming excellent at it. One of these normal pains was the toughening of the grip. The more we’d all practice, the longer we could hold on, the more our flesh right at the tops of our palms would rub and rub against the bars. Then it would blister. Then those would pop. Then that skin would toughen right up as soon as it healed. After class or rehearsal in the winter, we’d all exit the studio, and all in a pretty dancer row, grab the frozen metal railings outside with our bare hands, a chorus line sighing in relief. I remember making a joke once that I could see blood-colored steam rising off my section of icy metal pipe. But that was how we toughened up—that pain was the only way we could get good enough to begin to do the really amazing stuff, or hold those cool poses longer, or fly higher since we could hang on longer.

“A champion is someone who gets up when he can’t.” Legendary boxer Jack Dempsey’s words echo down the decades. This is what it means to train, or so I learned as truth as I trained in my several combat arts. Especially as the only girl training in traditionally masculine systems, there was no excuse for anything less than my all. More than my all—I was required to be the best, strongest, toughest. Better than all the men. I had to be able to take it, and get back up. Every time.

Martial arts of any kind, both in practice or performance and in training, are a process of pain. Dance actually is too—though the end result on stage or screen isn’t the obvious violence that boxing and other martial arts are, just ask any professional level dancer, especially those in particularly punishing styles like ballet or aerial, and you’ll hear some pretty gnarly body horror stories. In Frequent Flyers as much as in my later martial arts dojo, a gleeful showing off of bruises, rope burns, blisters and the like was a celebration of our physical prowess and accomplishments of the day.

It’s another fetish: a cultural one more than a personal one. The fetishization of the tough guy, of taking pain without showing distress, or damage. Jonathan Gottschall returns to this question of why we3 love it over and over as he moves us through his process of training for the UFC in The Professor in the Cage: “This invites an obvious question: if it hurts so bad and sucks so much, why do we do it?” Gottschall answers his own question right after asking it, on the next page. He basically sums it up in a so-bad-it’s-good conclusion:

“…the blubbery, congested sensation of incipient middle age gives way, and I feel young again, and strong. … I leave the gym feeling so awake, my whole system revving with something purer than a runner’s high.”4

Purer than your basic athletic dopamine surge, that is. Why is the pain from the violence of boxing purer than, say, the pain of long-distance running? Something about the valiant violence echoes in a cultural admiration of the rugged pioneer who endures unthinkable trials, gets up from unendurable pain, and is therefore holy. It’s the fetish of the enduring cowboy, the suffering saint, the Savior himself. Without suffering, he’s no hero. If he complains or becomes weakened from surviving said suffering, he’s not worthy of the heroic name.

And this concept gets dangerous when you add another cultural fetish to it: the woman-teacher-mom martyr, suffering virtuously in heroic silence, “like patience on a monument, smiling at grief,”5 sacrificing herself for our kids. It’s all related: rugged individualism, one-man pioneers, and we’re all Jesus, miraculously rising from the impossible abyss of pain, alone. At least, that’s the only guy who we keep telling stories about. That one guy. If you’re not feeling it, really feeling it, you must not be really doing it. He gets up when he can’t. So do we. Does that mean we’re that good? That virtuous? Then again, tough guy stuff is a pleasure in itself. Pain just plain feels good, there’s no denying it. Holier or no. Out of spoons?6 Get more spoons. Use knives instead. Get up.

In today’s culture, though, that raises a new question: what’s abuse, and what’s tough training? Is there a difference? Do we conflate these things, in our pioneer- or martyr-fetishizing? Survival of the fittest, but why should we have to survive certain things? The resilience of Gen X, okay, but why? It’s not fair. We didn’t deserve that. But then my tough-guy nature kicks in and I say: so what. What do you mean, not fair? Nothing in life is fair. Nothing.

Get up. Maybe you’ll win next time. If not, get up. You’ll win the next time after that. Or the time after that. Simon says: Get the fuck up…7 Get up, or there’ll be no next time.

The show I first began dancing in with Frequent Flyers took many hours of rehearsal time, and had choreography that was both chaotic and intensely sensual. Part of the sensuality was the enjoyment of the chronic pain that we all enjoyed. I found the beginnings of my own bisexuality just beginning to glimmer into view, in rehearsals, mainly because of a wee forest creature named Kristy…actually I don’t know if she was a repressed bisexual herself, or a captive tree-dryad. She was married to an older man, had two small children, lived way up in the mountains, and was a florist by trade. She was five feet tall barefoot, and could hold herself upside down by one pinky finger in the trapeze ropes, it seemed.

She would greet me each evening at the dance studio by literally climbing up my body, biting and kissing me, as a regular greeting. I would stand there rooted like a tree and she’d clamber her way up me till I was holding her like a child, her straddling my chest and nibbling my neck, or my ear.

Whatever brand of fae Kristy was, she manifested to us mortals as a tiny redheaded monster8 who could do the aerial art form so crazily well, she played a spiderlike character our second year with Frequent Flyers. Her parts of the dance involved climbing up trapeze ropes all the way into the theatre ceiling flies, where she waited, suspended by only a single strap, till a gripping dance piece where she’d climb back down the ropes head first onto a waiting, blindfolded victim, who hung there by his hips. Once descended, she’d manipulate him into gymnastic shapes in the trapeze rigging, changing him into a creature like her with one spinning bite.

That wasn’t weird—the show was called Theatre of the Vampires, after the Anne Rice novel Interview With a Vampire and its sequels. One national review of our show quipped that the performers were so gleeful and sinuous in our portrayals that we were “chewing, not on the scenery, but each other.” And boy, did we ever.

Act 1 of Theatre of the Vampires began with lots of stage fog rolling across the floor, the music not much more than sepulchral bell tolls. It evolved through a strangely haunting gestural piece made from hand signs the Artistic Director had seen in a dream, and culminated in the taking and turning of the vampiric initiate, as described above. In between all the heavy, sexy without the actual sex, darkness that was the dancers flying and floating and dangling and peeling up off the floor, a beautiful journalist character would venture onto the stage, recording her observations into a tape recorder. The premise was that she’d been hearing spooky stories about this Theatre des Vampires, and was investigating the sinister rumors. World-famous juggler Jon Held played an elder vampire and French-accented emcee and was a fourth-wall breaker. He bamboozled, seduced, and evaded the questions of the journalist, until he made her an offer she couldn’t refuse in Act 2, that of immortality, represented by luminous paper soul lanterns that magically bounced and floated through the darkened stage space.

Act 2 consisted of a sort of cabaret-like collection of different (much lighter) pieces, from a bloody and bruised young human in pointe shoes being teased, killed, and fed to the newly turned, to a fight scene between the bigger and manlier characters, to a jazz funeral for the victim, to a drag-like piece involving a flying coffin and the old folksong ‘The Worms Crawl In.’ Especially act 2 was inspired by and based on the Theatre of the Vampires idea from the Anne Rice vampire novels, which I was a staunch devourer of back then. Act I, in other words, was a sort of voyeur’s view of the flying undead, and in Act 2, the audience transformed into the audience of the show within the show.

I had been taking classes for nearly two years at the point where I began to get cast in Theatre of the Vampires. I appeared in it 3 times between 1996 and 1998, overlapping the two years of Renfaires with the Band of Young Men. Fun fact: when I was having some wrist pain issues, I went to a doctor, who asked what my activities were. I described my day job as a library shelver, the role of Peaseblossom for which I had a giant fairy puppet strapped to my wrist. Then I noted my work with swordfighting and trapezes. He shook his head and said, “Yeah well, no kidding your wrist hurts. You’ve nearly got carpal tunnel, and I’m amazed it isn’t worse, quite frankly. Take it easy on it.” Which of course he knew quite well I wouldn’t do.

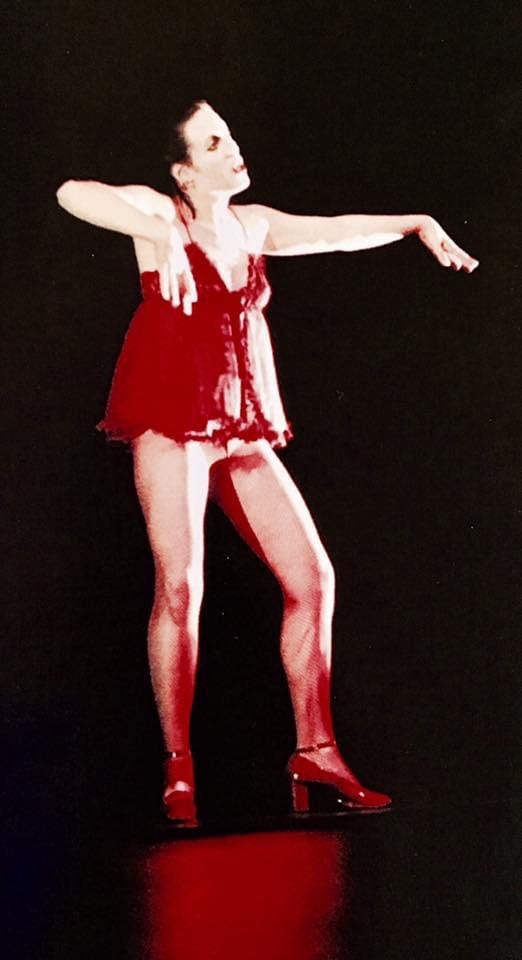

My Vampires part got bigger each year, but I always sang ‘Worms Crawl In.’ I think of it as the kernel of my performance in that show, and it foreshadowed my future activity in burlesque.

Ninjaboy muscled his way into that part of my life pretty early on: he came to see me in the show when we first began to think about maybe seeing each other, and then somehow he made his own movement prowess known to the Artistic Director, who promptly began casting him too. I don’t blame her—men who can move well are few and far between in the dance world, and he looked good with painted abs and red flowing vampiric hair, like a character right out of one of Rice’s novels. Looking back, I can see how he was the beginning of the end for me in that group, and can also see how that was one of the first steps in his complete takeover of my life. The first part of what would be my total isolation, no friends only mine, all activities social and professional done with and/or centered around him. It was subtle, insidious, impossible to detect at that time. A vampire—talk about sucking up my lifeforce.

It surprised me how big my roles in Vampires ended up being, progressing into sizable, even central, roles in other dance pieces. All the while the director continued calling me a non-dancer. She had said, one day in advanced class, that if we wanted to be cast, we should show up to rehearsals. The more we showed up, the more bit parts she’d give us. I never ended up with a bit part, myself, though—I was central and pivotal from day one, and not only appeared in most of the show as a dancer, but I was assigned a special task, to compose a piece myself, that would be paired with the huge flying coffin. This would become ‘Worms Crawl In.’

I don’t know why she put me in as such a primary dancer through that whole show, when she clearly didn’t think much of my dance ability. She had a sycophant, a sort of aerial major-domo that was completely smitten with me as well as with my talent. She would co-teach most courses with the director, and functioned as a consultant and assistant during rehearsals. She’d also play roles in all the shows, but then the director cast herself too, so that wasn’t too unusual. This right-hand woman certainly advocated for me more than once, and I have to think it’s because of her cheerleading that my parts got bigger and bigger each year. But it’s also true that the other dancers with arguably better technique didn’t have the dramatic chops I did. It was apparent that I could take over the stage with my mere presence, and since my skills weren’t anything to sneeze at to begin with, put those things together and I was a star.

The Christ Hang ended up being a particular specialty of mine during my tenure with the troupe. There was one piece I remember that focused on religious themes, with the one central apparatus being a sort of padded seat with very long, very thin ropes fastened to a single point—sort of like a lower, wider, softer trapeze or a strange swing. One of my pivotal parts to that piece involved me hoisting myself high on those thin ropes, holding a Christ Hang with arms nearly parallel to my shoulders (a real crucifix shape). I held this for almost a full minute, as the other dancers did group worshipful movements below. I don’t know if I felt more like the prow of a ship, or the crucifix art hanging high over a church altar. I hadn’t been to church in years back in the ‘90s, though the “fragrant offering” of Christ’s sacrifice was an image I carried with me even then. I still think of that long-held position, how the thinner ropes bit into my arms more harshly than those of a trapeze, and how it felt to let my lat muscles sink into that pain with my own weight. I think of it especially when I’m in Denver’s gorgeous Episcopal cathedral these days. How my feet floated free above the padded pew that I lifted with my breath and my strength. How it hurt. How good that felt.

After rehearsals or classes, no matter the weather, the regulars and biggest stars of Frequent Flyers would stand around in the parking lot, chatting and debriefing, and smoking. We would often plan our night’s social outings there in those smoking circles. At first, I never smoked—even though I had learned how to smoke a cigarette in a play not long before this, I didn’t like the taste. The smell wasn’t bad, it actually reminded me of a boyfriend I’d dated for a summer back when I was only 14. And I had always liked cigar smoke, because my grandpa smoked them and I had a positive association with him (unlike most of the rest of my family). So each time we’d do it, I’d refuse a smoke, but I’d still hang out. Then once, one of the dancers asked me why. I said, “Oh it’s no big deal, I just don’t like the taste.” He handed me his dark brown cig, and declared, “You’ll like this!”

It was a clove cigarette. And he was right—I loved that spicy, Christmas-cookie flavor. I smoked cloves from then on through the next couple, almost three, years, and even branched out into pipe tobacco. 2-3 smokes a day. Of course, cloves are exponentially more damaging to the body than regular cigarettes, which is why I stopped after a while. But there it is—another beautiful, tasty, sexy form of self-destruction…

The Artistic Director of Frequent Flyers had this amazing, larger-than-life pine coffin she’d had constructed in a way that it could be hung from the flies, two dancers lying inside, and be swung hard, rocking in giant arcs back and forth across the whole performance space, to a spooky rendition of “Row Your Boat.” The two vampire ladies would clamber over each other, smoke fake cigarettes, and flowingly act as though the flying coffin were a floating boat instead. The Artistic Director wanted to add a level of camp to that piece, so she assigned me to go find the lyrics to old folksong “The Worms Crawl In” that I would sing, drag-queen-like, as the coffin flew and the ladies acted out the decomposing body parts the song described. I compiled the lyrics and composed a vampiric conclusion to them myself, and then I sang them in a little red teddy way skimpier than anything I had ever worn before. I was never miked, either—the one time we performed in Denver’s huge opera house, I still filled the auditorium with my voice and my proto-burlesque self.

When I left the troupe because of entering grad school (among other conflicts), that piece got taken over by other troupe members with less charisma, at least that’s what I was later told. This meant they had to compensate visually: A tall, shaven-headed, fallen-angel-looking dude was added to the piece, to up its impact in my absence. He was led onstage with a leash, dressed in nothing but leather straps, his already considerable height made at least 5 inches taller by a pair of clear lexan stripper heels.

About 20 years later, Frequent Flyers were putting up an abbreviated version of Theatre of the Vampires, with a few selected pieces of the whole only, for a big fundraising event. The director had been following me on social media and so saw that I was active in the variety show and burlesque scene. She asked me if I could come back and reprise my ‘Worms Crawl In’ number. I agreed wholeheartedly—that many years later, I was much more comfortable performing in hardly any clothing. In fact, by then I owned some cool strappy corsety buckled leather stuff myself, from my several burlesque exploits. It was an echo into my past, strutting onto that stage, listening hard for the difficult sound cue which was my signal to begin singing. The tall fallen angel was lovely and courteous and good to perform with, and had a tuneful, mellow, voice. We even did a preview of the song part only for my variety show, Blue Dime Cabaret.

It was a little emotionally difficult though, to watch the dancers do all the graceful aerial work that used to be mine, though I knew very well I didn’t have the training or the grip stamina anymore to attempt even the easiest moves. But I could still channel my inner sexy bloodsucker, and sing, and steal the spotlight even from those levitating in space. I could hold the rapt audience in the palm of my hand. And for one rehearsal when the director was out of town, she had me step in to give notes as an assistant director of sorts. Not a bad gig, for a ‘non-dancer.’

After the showcase version of Vampires was successfully concluded, we agreed that next time Frequent Flyers does this show, I would be a great Emcee character, in Held’s absence. Who else has the kind of stage presence, charisma, and ability to speak and sing onstage, to guide the intrepid journalist and curious audience through all the mysterious and dangerous shenanigans, with aplomb and a secretive smile? Who else, amongst the dancers who can dance and dance only, can give the impression of immortality? The Trickster’s gravitas and glee?

The feeling of aerial dance is difficult to describe adequately to one who hasn’t tried it. It’s a feeling akin to what I imagine a daredevil, a tattoo addict, or a skydiving enthusiast feels: it hurts, it’s dangerous, even when you do it well. But along with the pain, the rope burns, the bruises, the calluses on hands that can only develop through popping blisters and tearing off bits of flesh, is an exhilaration close to ecstasy. The pain of the techniques is the pleasure. Not in spite of the pain; because of it. I had a similar experience in martial arts later—with that kind of extreme physical training, the pain is part of what makes it feel so good.

I still dream that I can do it. I wake up from dreams where I’m doing all of it again (and often my dreaming brain ameliorates it with thinner ropes, one handed grips, and more) and I feel wry, wistful, a little sad. Part of me wishes I’d kept with it all those years so I could still do it like the others that are still there and active from that time that I was. Most of me, though, knows very well I wouldn’t be able to keep up with the company’s updated skill requirements, and I would never give up my post-aerial years in the martial arts for anything. But still.

I tried aerial dance again just before the pandemic hit, more than 20 years after my vampiric stardom. I took a beginning level class as payment for my appearance in the Vampires showcase, and was astonished how hard it was for me. I shouldn’t have been surprised: not only was I in my late 40s instead of my late 20s, the rigorous and regular training just wasn’t there, and hadn’t been for years. They kept saying I’d get used to it again if I kept with it, but I don’t know. I really don’t think it’s anything within my wheelhouse anymore. Though I do have a picture of me in a Christ hang from that brief lesson. It wasn’t as good as it used to be: I could hold myself up just fine and the rope burn felt great. But I couldn’t lift my arms very far at all—they stayed at an acute angle from my shoulders, barely lifted. The trapeze bar was only halfway up my shins. The small and barely not teenaged instructor took a picture for me, after I got her approval to do this move that was not on the beginner list of techniques. In it, my face shows the joy, and the effort. But that’s it. I have to let go of it, I know I do. I have to step off the bar, metaphorically this time.

It feels like regret. I remembered; my body remembered, how to do all of it. I just couldn’t. What happens to the champion when he actually really literally can’t get up this time? What happens to immortals when they become mortal?

When I left Ninjaboy, he lost everything he owned, and went out onto the streets. This meant that he also lost whatever of my possessions I had foolishly trusted him with. Including our cats. That’s something I have had to work to let go of—it’s been a process, each time I remember something I used to have or can’t find now, like a fossilized lightning bolt, or a family picture, or an album full of photos from Vampires and that review of our show in the national magazine, I have to take stock. And I have to remember that it’s gone. We shared everything, so now a big chunk of my life (or at least memorabilia from my life) is gone because of this. Even if we were currently communicating, that stuff would still be lost. What I do have is a very small sliver of online remnants, and my memory. I need to make sure I cultivate that system of memory and let it bloom, or it will die again under the smothering darkness of his dominance and gaslighting, even though he’s no longer in my life. It wasn’t just money, or self esteem, or time, or gigs, that he robbed. He took everything. That’s the phrase: forcing himself on me. He forced his way into all these things I was doing, thereby robbing me of literally everything. And now I don’t even have all the memorabilia; he’s robbed me of that too.

I was raised poor, and so my knee-jerk reaction is to remind myself that it’s just stuff. Sure, but. A lot of that stuff isn’t replaceable. And a lot of it is stuff that is in fact important. It’s easy to take to the virtuous adage “it’s only things; things can be replaced,” but can they? Can they always? Photos are just things, but I have almost nothing digital left from that time in the aerial company, and Frequent Flyers has hardly any from then, either, and nearly none of me. I used to keep old family pics as well as pictures from older theatrical shows, and none of those are digitally anywhere. There were some thumb drives that I filled from the physical photos, right before I left Ninjaboy. I left them, I thought temporarily, with him, but of course those too were lost in his self-imposed devastation. Both the physical photos and the thumb drives, now. That’s not “just things,” that’s my life. Those are my memories. Those people (including myself) that were there for certain live shows might or might not remember them, but. Am I thankful I got out of that marriage and saved my life, if not my stuff? Sure. But I couldn’t save my cats. Are they just things? They can’t be replaced either.

I’m not immortal, or undead. I do go on. And my memories are resurrecting, a little, within this work. I’ll get up, even if I can’t. At least, I’ll do my version of getting up, such as it is today. And that’ll have to be enough.

At the time, I thought this added an air of legitimacy to the troupe. It was a level of badassery I was already heavily dependent on for my psychological well-being in the BoYM, and the way they scoffed at mats was akin to the way my martial arts practice, later, would scoff at gloves. Not that there weren’t totally reasonable reasons why these safety measures weren’t used (especially the gloves), but to me it wasn’t about that, it was about being real. A real tough guy. Someone that wasn’t faking it; my art was authentic.

Those scary and oddly sexy demonish beings from the Hellraiser movies. You know the ones—they’re headed by one called Pinhead. See, now you’re picturing them.

Actually, he avers that it’s really only men that love fighting, violence, and pain. I’d disagree just because of my gender and my affiliation with exactly what he describes, but then. I am one of the guys, so.

Gottschall, p.130,131.

From Shakespeare’s 12th Night—a fascinating discussion between two characters about how men and women love, and can love. A pretty amazing time capsule of relationship philosophy that still rings true.

Spoon Theory is a relatively new concept coined to describe the experience of living with chronic illness like autoimmune disease. The idea is: a person only has a certain number of spoons per day. Doing tasks takes away one or more of those spoons, and when you’re out of spoons, you’re out of energy and become non-functional. Spoon theory lingo has become common slang for “I don’t have the energy for that” or even “I don’t want to.”

Pharoahe Monche, “Simon Says,” from Internal Affairs, 1999

I’m realizing I need to have maybe a full sequel wherein I discuss my attraction to unhinged redheads, of any gender. You can see how they recur. My partner is one, even. Well, he used to be…

Great chapter, Jenn - I really like the way you build toward that loss of mementos that haven’t been digitized, because that is a real loss. It’s not just “things, “ especially if there are memory gaps.

Wow, that's a bunch of intense stories tied together.

Just thinking about the arial dance, I'm curious if you've seen "Born To Fly" about Elizabeth Streb: https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/documentaries/born-to-fly/

The documentary is very much about the questions about art that is inherently physically dangerous. I don't have much perspective of how high the level of danger is. I found the documentary fascinating. I shared it with someone who I knew had a lot of Martial Arts experience and was surprised how strongly negatively he reacted -- he had an immediate response of, "I don't think it's possible to do that safely, and I think it's almost immoral that she's trying. "

I say that just as full disclosure, I appreciated the story of her trying to invent art that engaged her both creatively and athletically.