Next Time

2 Cruel Optimism

Toxic positivity is toxic. Cruel optimism is cruel. Hope is not always necessarily the healthiest life choice. There is no Next Time.

A quick note re: changing names of people and institutions in this memoir: In this chapter, I have kept intact the names of DU and of the two teachers of the Designing a Writing Workshop that I took at the end of my MFA. The rest of the names, when mentioned here, have been changed. Understand, I know how easy it is for anyone to find this information–it would be easy-breezy to figure out especially what institutions I’m talking about, but. I dunno. Feels better this way, know what I mean?

Chapter 2

Cruel Optimism

Sitting in an office chair that was a little too short for my long legs, I sighed to my Mom sitting next to me, “Thank you for helping me. I’m so angry at myself. I can’t believe I allowed this marriage to go on this long. I can not believe I didn’t end this years ago. What the hell.”

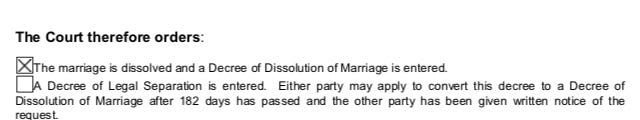

My mom had come up with the $230 to file the divorce paperwork. I didn’t have even that much left over from my paltry adjunct paycheck, and also was still waiting for my soon-to-be-ex husband to get his side of the paperwork done. I had been waiting three years for this to happen, though, so when Mom told me she’d just pay for it if I could get it done myself, and having lived alone for about a year at that point, I took matters into my own hands. I got all the paperwork done I could, had the meetings with the lawyer in charge of filing our case, and tried to get his papers served to him somehow (it was difficult, him being homeless and jobless). But I got it all done, and was finally doing the fee pay and penultimate filing to make the divorce final.

And I was angry with myself for allowing it to take so long. I’m an intelligent, strong woman. How could I have let someone drag me along like that, for a plural number of decades?

Mom turned to me and declared, “Oh, honey, you were just being optimistic!”

Shit.

Suddenly, a montage of some of my life from the last twenty years flashed before my eyes:

-my husband insulting me at a pub in front of friends, everyone laughing and me going to go cry in the bathroom (he was just joking);

-him arriving to the musical we were both in, too drunk to perform, and the fear I felt when he drove us home later (he didn’t realize it was that bad—he’ll never do it again);

-the post-coital texts I discovered between him and her who would later become our mutual girlfriend, before I knew they’d been seeing each other (but we had an open marriage);

-the time in martial arts class when he hyperextended my elbow to set a precedent for the other students (they were getting too arrogant and I was strong enough to help him set an example);

There were a few more events that spun through my head just then, some of them including police, most of them involving a very drunk husband in various dangerous situations. A vicious argument, a few nasty secrets, and the car I had bought for us (a pretty little Mini) completely totaled. I’m not comfortable going into those details here, but know that they flitted past my conscious memory in that moment.

Optimistic. Yeah. I had been. Making excuse after excuse. Staying attached, thinking that next time, it’d be all right. It’ll be better next time, or the time after that, or the time after that…

Mom was right. And there was no way, sitting there at the County Justice Center with a woman who’s been married to my father for a year longer than my forty-something existence (at the time), to explain to her how deeply messed up and wrong that optimism was. How much not optimism but pessimism would have saved me years of pain. And maybe her a couple hundred bucks. And me a car.

In general, I don’t have a problem with optimism. Or with hope. Or in making every attempt to work things out, especially if one has exchanged vows with a person. But there’s a point at which trying to be hopeful becomes pathology. There’s a point where all the members of the cult of positive thinking need to back off and realize that there is a place for negativity. There’s a point at which one needs to ditch the false promises and look reality in the face. I was attached to my own desperate reliance on the myth of “it’ll be better next time,” and before I knew it there I was: twenty years of trauma spooling through my brain as I sat in a bright, freezing, office waiting for my elderly mother’s card to go through, to save my life.

Lauren Berlant’s “cruel optimism” has already been cited in various articles as a vital component of discussing the tough academic life, most notably in an article by Jennifer Sano-Franchini called “Co-Dependent Emotions on the Market.” In it, Sano-Franchini describes the plight of the hapless adjunct attempting to attain a better position in academia as clinging to the old postwar myth of a “good life,” as well as that false belief we’ve all been fed: that a hard worker with good skills, a good heart, and a good work ethic, can achieve this fantastical end.1 She equates this hopeful clinging to the cognitive dissonance and emotional labor done by people suffering from the stress of relationships and dating. I’d take it one step further and equate the emotional stress to that of a victim of partner abuse. The wool being pulled over the survivor’s eyes is parallel in both cases: the gaslighting process, even the abuser’s word choice, is almost exactly the same.

The definition of cruel optimism as Berlant originally puts it forth is centered on this very problem: an unhealthy attachment to a “cluster of promises” that not only will never be fulfilled, but are harmful themselves.

“...optimism is cruel when the object/scene that ignites a sense of possibility actually makes it impossible to attain the expansive transformation for which a person or a people risks striving; and, doubly, it is cruel insofar as the very pleasures of being inside a relation have become sustaining regardless of the content of the relation, such that a person or a world finds itself bound to a situation of profound threat that is, at the same time, profoundly confirming.”2

Worse than the proverbial dangling carrot, and not in any way helpful in the way that hope can be, a cruel optimism is an attachment to the very thing that prevents the attainment of what one is striving or hoping for in the first place. For example, I learned late in my career that the fact that I’d ever worked as an adjunct, especially for as long I had, unofficially but absolutely took me out of the running for any full time or tenure track positions I applied for. The very thing I was doing, in other words, struggling to survive within, in order to build experience and my resume to move up in my career, is exactly the thing that makes sure I will never do so—that I’ll never be anything in academia but an abused adjunct. Nobody admits this, by the way—the exclusion of adjuncts in the tenured job market is an absolute, albeit unwritten, rule. I only found out about this rule after fifteen years of striving, wondering why I wasn’t getting the better jobs, wondering if maybe it was me. It wasn’t me; gaslighting abusers make their victims think it’s something they’re doing wrong. An abuse survivor ends up convinced that if they were a better person or worked harder they’d get their reward. Not true. The reward doesn’t exist. Next Time is a fiction created by the abuser, to keep them right where they are, convinced they deserve to be there.

Clusters of promises come in many guises—the vows of marriage are one example, but even more for me occurred much later in that abusive relationship—my own series of internal clusters of promises, even the ones approaching a good negativity. The self-promises, all internal, that almost but not quite got me out. Those attempts at self-assurance where I said to myself, “next time I’ll leave” or, “if it gets worse, then I’ll have a talk with him,” or the idle searches of vacant apartment prices on Zillow. It’s the deadly attachment and belief in the myth of Next Time. But when Next Time comes around? Another excuse, another promise. Another love-bomb by the abuser, just in case.

There’s the promise of upward mobility, when it comes to working in both adjuncting and the theatre, which is a classic dependency on Next Time. The next job, the next part, the next audition, and all the abuse you go through to get there is called “paying dues” or accruing experience as though you’re a Dungeons & Dragons character and not a human being. It’s the cruel optimism of the eternal Next Time that never comes and often doesn’t exist. Herb Childress nails home this point in regard to college teaching, in The Adjunct Underclass:

“But the bait is so, so appealing. It’s fun to be back in the classroom. It’s gratifying to have an email address ending in .edu. It’s heady to have the chair tell you how highly she thinks of your work, and to read the students’ pleasure (in you and in their own capabilities) in your course evaluations. Magical thinking takes over, and adjuncts can invest years in a half-promised permanence that they believe they might somehow earn.”3

Academia makes all the lip service and gestures which in any other profession would lead to a promotion, but which in academia, doesn’t. Ever. But boy, do they keep adjuncts clinging, hoping for Next Time…

That was exactly why I had stayed with my husband, why I made excuse after excuse for him, and allowed him to make his own. Not only was the promise of marriage vows hanging over all of that, but the cluster of promises of my future: I did actually believe that it was going to be okay, that next time it would be better. Or next time. Or the time after that.

The moment when I did finally manage to say, after one of the worst fights he and I had ever engaged in (and that’s saying something), “Look. This is very bad, it has been for a long time. It’s not going to get better,” my next sentence was, “It’s time for a divorce.” Negative? Sure. Pessimistic? You betcha. Healthier than remaining under the yoke of that false hope, though? Absolutely.

His response was, “Is that what you want?” I, even though still largely under his gaslighting, retorted, “DON’T YOU??” That’s what narcissistic abusers do: they turn situations around and blame those they're abusing. In this case, though, just the basic act of recognizing my negative feelings as being totally legitimate and important (and real!) was enormous. Life changing. Life saving, if I’m being honest—stopping the cycle of false promises is a big part of what finally dissipates gaslighting, and it certainly did so for my destructive cycle.

It’s hard, and painful, to cut one’s attachments to those sweet clusters of promises, but if you can manage to shake off that wool over your eyes and turn up the gaslight, you end up seeing much more clearly, and the world gets a heck of a lot brighter.

Back in 2001, I was about to graduate with my MFA in Creative Writing. I took a course that semester called Designing a Writing Workshop, taught by the legendary Jack Collom and esteemed Lee Christopher. It was during this class that I realized I could teach, and might even want to. I also was given a couple "in"s: to DU's University College (who, it should be noted, only employ adjuncts), and Subway University's English department. My interview at Subway resulted in being immediately hired on as adjunct, to teach Freshman Comp but especially to teach Intro to Children's Lit, as that is an area of expertise of mine. In fact, way back then, I was even asked to help develop the Intro level course, as it had been only upper-division before then. Suffice to say, I was hired not only because of general required credentials, but a specific realm of expert knowledge.

Things started going slightly downhill a few years later, when they hired a full time professor whose specialty is children's lit. This meant that he got assigned those courses first, and I was often passed over to teach them in favor of him, no matter my past help in developing the course, or how arguably better I was at teaching it.4 The downhill slope got slippery when another full-time professor asked me to give him my Harry Potter course syllabus. I had created and taught the Harry Potter course for DU as a literature course, and he wanted me to adapt it for Subway's infant Cinema Studies minor. I did so gleefully—I had taught Intro to Film not long before and had a blast—a page-to-screen class would be so much fun, and I know a lot about what goes into both mediums, as well as the Harry Potter story, it borrowing from all the old folktales and hero’s journeys I know so well. It sounded perfect for me. And, this being the early 20-teens, it would have been a wildly popular course.

My tenured friend came back a couple days later, dejected: the committee had rejected the course offering, for the following reason: the full-time children's lit prof might get upset if I were given this course to teach. Might.

It got worse for me over at Subway English when I began teaching for their Theatre department in 2005. This meant that my allowed total of three courses tops would have to span two departments instead of one. This may not sound like it would be an issue, but English started scheduling me in conflict with Theatre, a couple times without telling me, after I gave them my Theatre class schedule needs clearly. I once got double-booked by English with no email or phone call telling me they'd scheduled me at all, let alone in conflict with other courses. When I discovered this and asked to reschedule, not only did they have limited choices left for me, they made it plain that the clerical error was all my fault, not a lack of communication on their part. Remember that this was in 2006: I had been teaching for them for five years at that point, to positive, even glowing, evaluations by both my peers and students. Not that merit or seniority have any pull whatsoever for an adjunct...

And it got even worse. Once Theatre began giving me two classes consistently; one in my specific area of expertise: movement, and one general studies course, I was told that my one remaining course in English could not be hybrid or online-only. Never mind the grant and the awards I had received from DU in 2007 for my online course development and teaching, nor the availability and popularity of such courses. Nope, if one only teaches one course in a semester for their English department, it can't be online. When I asked why this policy was in place, I was told it was just a rule. When I asked why it was a rule, I was told that, well, if you teach online only we do that for those with disabilities or who aren't able to get to campus, you know, like so-and-so who had her baby last semester...I didn't bother to emphasize my lack of a vehicle, my commute to Denver from Boulder by public transportation, or my online education accolades.5 I let it go, only because I knew I could do nothing about it.

At this point I had been teaching faithfully for English for more than a decade. I was assigned a freshman composition class, and it got canceled due to low enrollment. Low enrollment is a plague of adjuncts, especially as we can't know for certain this will happen until usually about two weeks before the semester begins, making it exceedingly difficult to find a replacement for that income. The English department would set its adjunct schedules with request sheets that we’d fill out and submit to those in charge of scheduling. Partway through the canceled semester, I asked when I would be receiving my scheduling sheet for the following semester.

I was told that the sheets had already gone out to those adjuncts with classes, that there was nothing left for me. Astonished, I asked why I wasn't sent one. I was told that they only went out to those faculty who had classes. I reminded the person in charge that I did in fact have a class, only it had been canceled, through no fault of my own. I hadn't asked to take my name out of the running for the next semester, and I certainly didn't think I'd be twice screwed over because of one class not having enough people. I was told there was nothing to be done. So I asked when during the following semester the sheets would be going out, so I wouldn't fall through the cracks again. They told me when, and at the designated date I asked dutifully for my schedule sheet.

I was told once more that sheets were only going out to those currently teaching courses. That even though I specifically requested to be given a course for the following semester, they wouldn't be giving me a schedule sheet. If there were any classes left over, I was told, they'd let me know. I asked how I could possibly have gotten a request for a class in, if my class was canceled two semesters ago? So does that mean that once one suffers through one semester with no class in the English department, one is no longer considered eligible for teaching? There is an option on the scheduling form which says: Please do not schedule me for this semester, but do keep me in the English department pool for the following semester. What about those folks?

Or was it me? Had I done something wrong, that wasn’t showing up in any peer or student reviews, that made me unworthy of teaching for them anymore? Had I messed up? What had I done wrong?

I emailed the department several times, inquiring about my status, about teaching any classes, to vague replies. And then, to no reply at all. This was a few years ago now, and I have no idea if I'm still in their contract pool or not. I'm obviously not welcome to teach for them. After nearly fifteen years there, with good evaluations and useful areas of expertise, I was given no explanation for this treatment, nor any notification if I'd been "terminated." Just ghosted.6

Of course, adjuncts being the contract employees we are, it's not really a termination at all, and they have every right to string me along, refuse to assign me courses, and not respond to my communication. I had and still have no legal power to do anything about this situation whatsoever.

Being gaslighted can make a person feel like they’re overreacting, acting irrationally, or not perceiving reality clearly. In other words, a gaslighting victim will sweep their negative feelings about their situation under the rug, because they’re no longer sure what’s real. A survivor of gaslighting (especially women, as we’re more assumed to be irrational or hysterical) will have her cognition so screwed up from her abuser’s manipulation that she often will ignore her own loss of patience, her own loss of optimism. The litany of broken promises. She won’t recognize her valid negative feelings as being perfectly legitimate to her shitty reality, but will fall into her abuser’s repeated claim that she’s just being dramatic, or selfish, or irrational. And then will often come contrition, and love-bombing, which is even more confusing. If she’s not ghosted instead.

It’s not that bad, you’re making it up. You’re overreacting. It’ll be better Next Time. He said he loves you, how could you do this to him? If you leave, they won’t be able to put the show on without you. Don’t assert yourself; he might get upset.

Might.

Sano-Franchini, Jennifer. “Co-Dependent Emotions on the Market,” CCC 68:1, September 2016 (p.103-104).

Berlant, Lauren. A Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press, 2011 (p.2).

Childress, Herb. The Adjunct Underclass. U. of Chicago Press, 2019 (p.66).

My evidence of this is purely anecdotal: my data comes from students who have told me their opinions of both his courses and mine. Were they puffing me up? Maybe. But the ones that expressed this had no reason to, so.

Let alone what a dismissive, backward view of online learning this is. As though the only purpose of an online course is for those who lack capability somehow for on ground courses. I learned later that English had eradicated all their hybrid courses and drastically cut back their online courses. I can't see how that can possibly serve the students well. I wonder what they did during the pandemic lockdown...

Ironically enough, I had applied to Mountainside Community College in a panic right at this time, as an attempt to make up for the missing income. I taught freshman comp for them too, for a few semesters, until I fell ill once and had to cancel two class sessions (not two semesters—two hour-long class meetings, only). After this, I was not given any courses for the following semester, but told that if there were any left, they’d let me know. Sound familiar? I hadn’t heard from them for a few years before quitting Subway—I gave up inquiring if I was still in their teaching pool or if they had anything for me, after hearing nothing back. Ghosted again. But not technically fired. And so it goes...

I'm familiar with the academic life you write about, from every side and angle, including yours. It truly is an abusive, exploitative system, and it's painful to read about not as a systemic problem but as a person's life. Yay you.

Sigh. On point in so many ways. One of the underlying problems here is the power hierarchy in academic institutions - that hierarchy also exists in other media organizations such as book and magazine publishing. In the case of adjuncts or grad students teaching Freshman Comp, students absorb all too well that such a core course doesn’t matter beyond a graduation requirement - so the basics of effective writing at the college level are devalued from the start.

I’ve been mulling this over a lot in connection with the hype about generative AI being able to do the writing for you - total bs, especially if you understand that Freshman Comp is often the place students learn critical thinking, media literacy, and how to communicate with other human beings. Those fundamental skills are more crucial than ever now, yet they’ve been relegated to the equivalent of low-status service workers who can be “let go” at any time. Talk about gaslighting, from the likes of Sam Altman to department heads who only listen to “ladder faculty” (that term says it all) to an administrator who parrots like a bot, “it’s the rules.”