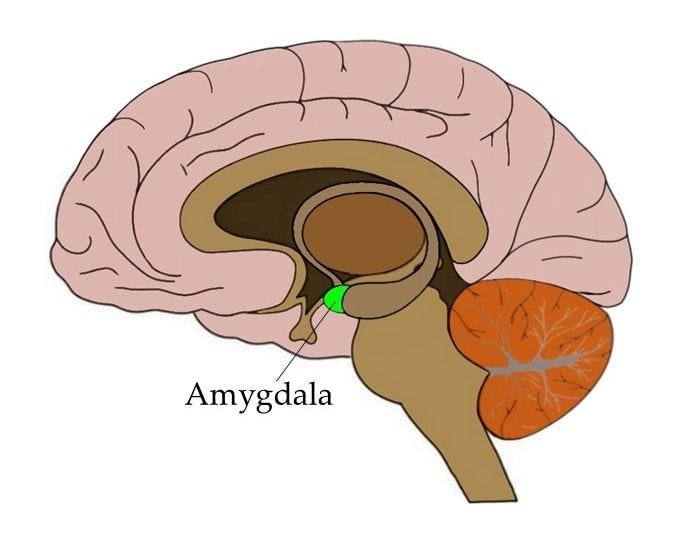

Amygdala

I'm realizing how many of our Vocab Words o'th'Week begin with the letter A. Huh. Weird.

This post first appeared on me ol’ blog, in August of 2019, back when I was first trying to bring my body language program to the biz world. What does it have to do with today’s word: Amygdala? Well…I think you’ll get the idea.

Back in my twenties, my main day-job was as a full time worker in a place not unlike Kinko’s (remember Kinko’s?): we made copies, did some graphic design, but mainly made good looking hard copies of things (brochures, booklets, presentations, etc.) for the professionals of Boulder. I worked in the bindery—a big warehousey area in the back where we had one of those huge industrial blades you had to operate with both hands, comb binders, wire spiral binders, two folding machines that always did their job crookedly and with mild electric shocks to the laborer that wasn’t paying attention.

But the biggest, oldest, most intimidating monster of a machine we had back in the bindery was something called the Perfect Binder. This was a brand name, though those of us unfortunate enough to have to use it (pretty much only me and the manager), agreed that the moniker Perfect for this thing as a decidedly ironic descriptor.

The Perfect Binder was the size of three clothes washers lined up side by side—basically, a huge solid steel behemoth that took up almost an entire side of the room. Its job was to create “real” looking book-style bindings: it would roughly trim one side of a stack of paper, apply piping hot glue, and affix a cardstock cover to same. Thing is, this machine was a relic of the Industrial Revolution, and thereby needed a human (with ear protection, of course) watching it at all times to supervise the process—why, it’s hard to say: if one got anywhere near the thing as it ran, there was real danger of injury. But if you didn’t attend to it, it’d spew out glue-encrusted abominations that looked nowhere near Perfect.

Suffice to say, the Perfect Binder was slow, painstaking, and LOUD when it was working correctly. One day, I had a sizeable order that needed to be Perfect Bound, and the machine wasn’t working right—it was getting paper stuck in its craw, and basically wasn’t doing its thing. I got the manager, one Jamie, to come in and help me assess the issue, so he came in and put on his ear protection. We put a sample into the Perfect Binder, and turned it on. Only a couple seconds into its faulty process, the whole room-sized thing JUMPED and jammed, making an even louder, sharper, and more alarming roar than its usual, before it conked out, secreting hot glue.

Once it had turned itself off, I sort of came to and looked at Jamie and myself. I had taken a quick step back away from the machine, and I was standing there rigidly, my arms up over my chest, forearms covering my breasts, fists positioned just under my ear coverings. I looked over at Jamie, who had been standing next to me as we had flipped the On switch. He, too, had taken a big step back in a natural flight response, but he, though standing just as stiffly as me, had both his hands crossed in front of himself, covering his groin.

I looked at Jamie, and at myself, and started laughing. He asked me what, and I indicated how we had both reacted (we were both still frozen in our respective defensive positions). Once we relaxed enough to take our big headphones off and realize the Perfect Binder wasn’t going to come back to life and kill us, we marveled at the gestures and movements both of us had made, completely without thinking, in the face of danger. I was amazed at the gendered reactions—I had covered my chest, his protective hands went right to his groin—and he was more amazed at the very big, clear poses we had adopted, entirely without consciously doing so.

Now, I’ve been in theatre since I was a very small child (my mother was a dance education major at SIU when she became pregnant with me and so I always joke that I’ve been appearing onstage since *before* I was born), and professionally so since my teens. I’ve also been presiding over classrooms full of people for the past 25 years or so. I say this because, unlike most humans, speaking onstage in front of an audience is not one of my greatest fears. In fact, I’m not afraid of it at all anymore—it’s completely second nature and I do it pretty much every day.

But most people are just as afraid of getting up in front of other people and speaking, as Jamie and I were of that malfunctioning Perfect Binder. It’s terrifying for most, and for most, even if you’re a business pro that’s somewhat used to it, it will still fill you with life or death, fight or flight terror. And the big defensive postures most people will perform while onstage? They won’t have any idea they’re doing them, no more than did Jamie and I. But imagine: you’re a male executive, doing an important presentation in front of something just as scary and intimidating as the jamming Perfect Binder; say, a panel of Fortune 500 C-suites? What impression are you going to give, standing stiffly in front of them, both hands clasped over your groin?

If you don’t have the kind of training I do (and why would you, unless you happen to have undergone a rigorous training background in theatre), no matter how smoothly your rehearsed speech might be in your voice, no matter how awesome your PowerPoint slides are, your body will belie all of that. Your body tells your real story, and it doesn’t lie. It can’t.

This is why I’m bringing my wide movement expertise into the world of business—I know how to get your body to tell the story you want it to, to align the story your body is telling your audience in that lizard-brain, primal way, that no number of words can correct if it’s not right there with it. Thing is, I don’t do a one-size-fits-all boilerplate for this. Sure, there are certain physical techniques I like to share with all of my clients, but I don’t go in and “correct” people’s “wrong” postures; I work with each person’s particular strengths to align their physical storytelling with their verbal message. And it’s kind of a bonus that some of the breathing techniques I work with do in fact soothe stage fright quite a bit.

I’m an English and a Theatre professor and have been a stunt coordinator for 25 years. I’ve survived the Perfect Binder. I know how movement connects to message.

How can I help you?