Problematic Toxic Masculinity Tropes #7

Violence is Normal

I’m starting with an ad again for our final PTMT. It’s for Gillette (whose slogan, remember, is “The best a man can get.”):

Guh that ad always makes me cry. Ahem…/attempts to salvage eyeliner/

Why does it make me tear up?*

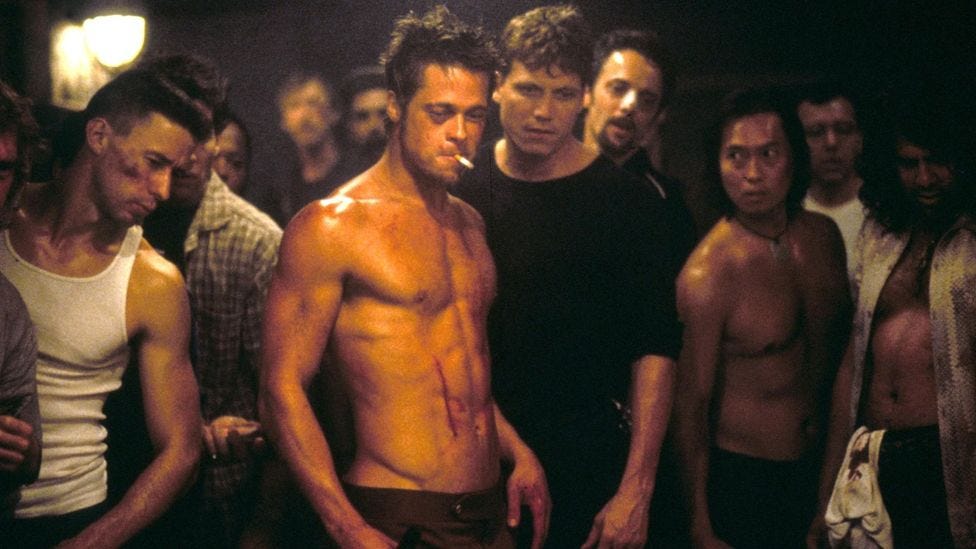

I think maybe it’s the sort of chantlike repetition of the cliché (boys will be boys) that eerily evokes the chanting of the brainwashed men at the end of Fight Club. Maybe it’s the showing of how difficult it is to break through this chant—what it means to say No to it. But the norm is powerful and real, and even in this supposedly enlightened year of Our Lord 2023, it’s still a powerful message being given to our boys and men today. And let’s be real: #metoo is directly and literally because of this… well I was going to call it a trope because that’s what I’m talking about with this series of articles, but this one is far, far more than a trope; it’s ingrained not only in our arts and our pop culture, but in our whole way of being, our society at its roots, and maybe to some extent, our biology.

Toxic Domination

Okay, before I go on, I must reiterate the center of what’s actually toxic about these Toxic Masculinity Tropes: it’s the emphasis on domination. In a toxic masculine norm, the domination needs to be absolute, and (actually in all 7 tropes I’ve described) is usually maintained with violence. In other words, the only power is violent power.

Masculinity is NOT toxic in and of itself. Even violence isn’t bad automatically, in all contexts. Being a man does NOT mean that you hate women or that you find femininity to be shameful. These articles, of which this is the last, are all about calling out the TOXIC tropes that we get fed ad infinitum about gender and how we as a (binary) gender need to act accordingly. These problematic tropes are those things: problematic, and tropes. This means they’re not real (and they’re wrong), also that they repeat, permeating our culture. Real men irl are able to make choices.

However, it’s hard when you’re being so inundated by it. This trope in particular is absolutely everywhere, and is even in our biology (but only to some degree).

*and after this ad campaign made its rounds, the size of the backlash was massive. Counter-videos and panicked hypermasculine hyperventilating was truly astonishing. The best a man can get, indeed. If you’ve noticed the man v. bear discourse happening now, it’s similar.

By pointing out how these tropes are toxic and problematic, we can liberate people of all genders to make choices that aren’t in line with these damaging social norms. And then we can make a change. Being masculine isn’t in itself toxic. But oh, how many ways does our society try to make it so…

Here is our final Problematic Toxic Masculinity Trope. It’s called:

Violence is Normal

This trope encompasses or umbrellas all the rest of the PTMTs. It’s everywhere.

The basic premise of this trope is as follows: Violence is always the way a man will take charge (which is what asserts his masculinity). If we remind ourselves that the central toxic mode of these tropes is about domination, then we can see how violent domination is the only way, in pop culture.

This trope may not even be its own thing, but an insidious aspect to all of the problematic tropes I’ve described already, both Badass Female and Toxic Masculine. Just look at how it comes into play in each of the PTMTs that have come before: (For more details on those tropes, go to the articles themselves to read more on them.)

1: Go Big or Go Home: this trope is about the importance of size—in other words, being big equals the ability to administer physical/violent domination.

2: Grow a Pair: stoicism and violence go hand in hand; both violence to the self and to the other.

3: Bond, James Bond is all about violence against those who are inferior. Which is everybody.

4: NERD! This trope teaches us that nerds don’t have the violent prowess to keep up with hegemonic masculinity.

5: Sassy Gay Friend: similar to nerds, SGFs are incapable of violent prowess (and are often victims of the violent domination of those who exercise it).

6: Mr. Mom is feminized by his nonviolent state, and therefore is diminished, made less masculine and less worthy.

Now that we’re talking about PTMT #7, I find there are too many pop culture examples to pick just one. When we discussed this in the Outrider podcast, we couldn’t think of a single movie that didn’t have violence as a central aspect. Not one. I mean, there might be one or two (like the woman-warrior-centered Old Guard) that aren’t particularly masculine or toxic, but the violence is certainly still there. Think about it. Even the movies you know that have no fight scenes, definitely have violence, and usually masculine-hierarchy centered violence at that. Can you think of one that doesn’t?

Not My Monkeys

The major problem with this trope lies in the following toxic premise: Violence equates masculinity. Violence is Normal will tell us this in many different ways, including: action flicks, rom-coms (which often are worse); and from there into real life in the form of bullying, and derogatory language (pussy, sissy, wimp, beta, soyboy) to denote a non-violent, aka not a real, man.

Everyone’s favorite pop-neuroendocrinologist Robert Sapolsky discusses the biologically ingrained ways that humans enter into relationships, and you can understand why it can get confusing for a boy turning into a man, especially when soaked in PTMT #7. Basically: apes and other primates fall into one of two categories as far as their social structures. You’ve got your Tournament species, in which an ‘alpha’ male will (violently) compete and dominate for the viable females—you’ve seen this in Nature shows when looking at baboon society, for one. Then there’s what’s called Pair-Bonding species, who don’t compete and dominate to mate, but everybody gets the opportunity to court, pair off, and mate monogamously for life.

In the former way of life, there will always be some males that don’t get to mate at all (and therefore miss out on passing on their genetic material). In the latter, usually everybody gets to mate. Here’s the thing, though—if you’re finding that both of these social scenarios sound like what humans do (dominant males competing for females, and pair-bonding mating for love and life), that’s because both are. We’re primates that aren’t all one or the other. We humans function in between Tournament and Pair-Bonding, and we function as either or both. We don’t really have the ‘alpha’ male dominating all of our society, biologically, and yet? And yet, we do, though, don’t we.

(This is a very generalized description—For more fascinating talks by Sapolsky, just go down the Stanford lecture rabbit hole—I guarantee it’s some of the best brain food you’ll find. Here’s one of many.)

So, violence is in our biology. Does that legitimize it? No, but it does show how very immersed in violence men are, and why the trope shows up anywhere and everywhere, not only in literal fight scenes. The violence of society’s hierarchy is deeply ingrained in how men behave. “Boys will be boys” is an apology for this; extremist groups like the Proud Boys are a dangerous eruption of it.

Human men, though, aren’t baboons or bonobos: men are men, and men can make a choice. But this choice-making starts with how we entertain ourselves, how we build our culture, how that culture then influences our beliefs in our real lives, and to what extent we allow violence to be infused into our everyday consumption of arts and media.

Of course, when I first wrote this article on a September day in 2020, I was thinking about the BLM protests, and how much real state-sanctioned violence is normalized, and how police brutality is finally being questioned, after George Floyd among other victims of it: why is police murder such a commonplace thing? A capitalist patriarchy dictates that all real men are warriors, enforces a gender binary, and glorifies the individual vigilante as hero. A man in these sorts of glorified warrior professions daily drowns in hegemonic masculinity, and is forced to engage in hypermasculinity whether he wants to or not. In all of the stories we tell and retell each other, there’s a glorification and romanticism of the violent hero—either prevailing via violence or dying violently as a martyr (Valhalla is a mythical goal in our military-centered culture). From the knight in shining armor to John McClane saving his wife and the day, hegemonic masculinity requires violence to claim and keep dominance. What were the motivations of the insurrectionists of Jan. 6? A wresting of power, seizing dominance by using violence.

Men of Action

The Violence is Normal trope focuses on men being the, well, men of action, not women. Female action stars are very rare (thankfully getting less so but they’re still the unusual minority), and of course in Hollywood, non-binary genders don’t exist. Hegemonic-masculine men protect their women and children with violence; men leave the home to provide, but also to stand guard outside the homestead in order to eradicate interlopers who would steal his valuables (valuables that include his women and his children).

Quentin Tarantino is a filmmaker who plays with this Violence is Normal trope in especially his earlier films. He uses various techniques from camera angles to quippy dialogue to numb his audiences to the intense violence, and even to deaden them into laughing at gore—by doing this, he calls the trope into question, and makes us stop and think. I recall noticing this when I first saw Pulp Fiction in the movie theatre. It’s a film with much acerbic wit and lots and lots of violence. Late in the film, one of the last scenes of violence includes a gun accidentally going off in a car, and blowing a kid’s brains out all over the back seat. The scene is presented to the viewer as comedy, and the frantic dialogue of the killers afterwards only adds to it. But I remember stopping in the middle of my chuckling and taking a good look at myself. I thought: Wait, why am I laughing? This isn’t funny, this is bloody and horrifying. Or is violence so normal that maybe it actually is funny? Whatever you may think of Tarantino, he’s definitely calling this norm out, and making us question why it is that violence is everywhere, and so “fun” to watch.

When I teach stage combat, I begin with the basic tenets of acting: a character is always going for an objective, and uses tactics to attempt to get this objective. His tactics perforce need to constantly change as he runs into various obstacles in his way. Every line a character speaks is a tactic. When the character runs out of words—when he’s said everything he thinks is possible to say and is still failing to achieve his objective, that’s when he resorts to violence. In other words, it’s only when verbal tactics run out that a character will resort to physical ones (I aver that this happens in real life too, but I’m not a sociologist). Why does so much of our entertainment / culture / art / media fast forward so quickly past the verbal tactics into the physical ones? Why are even the verbal tactics so often inherently violent to begin with? What’s the difference in psychological impact between physical violence and other kinds? Is it possible to have conflict in a story without violence? Do we need to?

Thank you so much for joining me in this journey through another 7 Problematic tropes. Let me know what you think about this or any of these tropes, and stick around to see what your special Paid-Only Wednesday posts will be like next! (Hint: pretty sure the new series will be called Fight Clip Club. So. That’ll be a thing. Come see!)

I wonder if these tropes actually derive from the fact that most men don't resort to violence; most men I know have never been in a fist fight (which was what Chuck Pahlaniuk was satirizing in "Fight Club"). And so looking at films as entertainment, perhaps the popularity of violence (especially the extreme kind a la "John Wick") is the playing out of internal fantasies for men who wish they could be more assertive, more like these characters? If you've always backed down from confrontation and suffered the humiliation that entails, wouldn't such films basically provide fantasy fulfillment of a sort?

I read this before reading the previous six; I'm looking forward to the others though maybe I'll start at the beginning...

The "man card" graphic makes me curious what you think about the Heinlein quote "specialization is for insects . . . " which I think is both less toxic and has a lot of overlap with the "man card" stereotypes.

As far as (fiction) movies that don't have violence . . . I'm tempted to say _Before Sunrise_, but you already said (corrrectly) that Rom Coms as a genre are often problematic. I'll think about that.