DU Villains, Monsters and Foes Lecturettes

This is a conglomeration of some of my online lecturettes from a now-defunct graduate-level writing and literature course that I created and taught at DU, called “Villains, Monsters, and Foes.” In it, we engaged in the overarching study of the villain character and looked in-depth at a three-pronged approach I invented for the course: the Monster, Fair-Faced Villain, and Villain Within. I’d like to hear your comments here in response to any prompt (which would have been for discussion boards). You’ll see a reading list from that week of the course at the beginning, and endnotes at the end of each section. Be advised that these are lecturettes for a class, and so are written with the assumption that you’ve read the works discussed. So, like. Spoiler alert, for all of them, I guess?

I do also want to go more into Marina Warner’s concept of the Beast-as-Cyborg, in a separate post of its own. Soon, I hope. I’ve got a bunch of notes on it already, and it’s exciting stuff to muse about. Hopefully I can cobble all those nerdings-out into something more coherent at some point in the near future.

But I digress. Here are 4 of those old lecturettes from that old Villains class. Please to enjoy!

Who is the Bad Guy?

Archetypes are forms, symbols, or images that have universal meaning and inspire an original model, or prototype.[1]

He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organizer of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order. He sits motionless, like a spider in the center of its web, but that web has a thousand radiations, and he knows well every quiver of each of them. He does little himself. He only plans. But his agents are numerous and splendidly organized.[2]

Okay, numerous and splendidly organized agents, this is the idea for the quarter: to explore many samples of the villain archetype, hopefully to inspire your own villain prototype to emerge.

Who is the villain? The antithesis of the hero? The hero’s best friend? That sinister bald guy petting his cat? Why does the villain hate the hero so much, and why does he make it a point to get in the hero’s way? What does the villain want?

That’s really the question, isn’t it—as realistic villains normally are after the same goals the heroes are. A non-stereotypical antagonist may not even understand his actions as being necessarily bad, or if so, may feel that his selfish or wicked actions are a means to an end. When discussing the villain Sauron from The Lord of the Rings, Paul Kocher asserts that evil is self-centered; that the essence of the villain is that domination-lust, the desire to be “king of other wills,” the intense (and often paranoid) protection of ego to subordination of all else, and the “lack of imaginative sympathy” is what the hero has that he lacks, which often leads to his downfall.[3]

Think about the overall theme of hubris, or overweening pride, as we explore the three types of villain this quarter:

The Monster: ugly, deformed, alien, artificial, bestial, the “other” in any way

The Fair-Faced Villain: the one whose villainy is hidden under an attractive façade

The Villain Within: split-personalities, either literal or figurative

we’ll also speak briefly about the anti-hero and tragic hero—not quite goodies, not quite baddies?*

Who are the already-written characters you love to hate? Why do you think they are effective as characters?

*I’ve lost this fourth lecturette into the ancient internet ether–sorry. I wish I remembered what we talked about, and what our readings/viewings were. I know I was playing and rather obsessed with the game-changing (!) immersive stealth videogame series called Thief at that time. I believe we had gotten to Thief 2 by then. Who else must I have talked about? Fafhrd and The Gray Mouser? Batman, maybe? Who would you all put in that week’s study, if you were curating this curriculum today?

…ENDNOTES

[1] Floyd Rumohr, from Movement for Actors, Nicole Potter, ed. NY: Allworth Press, 2002.

[2] Sherlock Holmes, from Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Final Problem.”

[3] Paul H. Kocher, from Master of Middle Earth, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. 1972.

THE MONSTER

For this week (Monster Week: rawr!), we read Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, and an article about Star Wars: Phantom Menace. I may have required the movie’s viewing too, but I don’t recall–it was right around the film’s release, I believe.

Be afraid…be very afraid…[1]

The wolf is carnivore incarnate; and he’s as cunning as he is ferocious; once he’s had a taste of flesh, then nothing else will do.[2]

The word ‘monster,’ from the Latin monstrare, to show, even suggests that monstrousness is above all visible. But monstrousness is…subject to historical changes in attitudes.[3]

…and I am…cute, too![4]

The monster is terrifying because it is other. The ugly, bestial, unnatural, the not-one-of-us, is potentially harmful and therefore feared.

Beasties

Back in the day, when you lived in a hut on the edge of a wild forest, when winter came, you’d better believe the Wolf was your enemy. Livestock, children, and even adults could fall prey to hungry predators coming too close to the village in search of food. Here enters the Big Bad Wolf, Killer Bear, Man-Eating Tiger, and the rest. Beasts also act according to instinct, unlike humans who have rationality to repress certain urges and behavior. So animals came to represent the “bestial” side of human nature as well. In this era of urban living and conservation, animals as such aren’t considered monstrous. In fact, we are so separated from our past struggle with animals that now beasts are cute-ified for nostalgia’s sake. As Marina Warner says, “Tapping the power of the animal no longer seems charged with danger, let alone evil, but rather a necessary part of healing. Art of different media widely accepts the fall of man, from namer and master of animals to a mere hopeful inclusion as one of their number.”[5] This being so, what is the Beast in recent myth and fairytale?

Beast as Cyborg

The artificial intelligence, living mannequin, the constructed man-made creature is unnatural, outside of what should be. This is a different tack on the monstrous—the robot monster “represents the apocalyptic culmination of human ingenuity and its diabolical perversion.”[6] Frankenstein’s Monster, the Borg of Star Trek, HAL from 2001-A Space Odyssey, those scary living mannequins in that one Twilight Zone episode, the Autons from Doctor Who, the rogue robots in I, Robot, Blade Runner’s replicants—all these monster characters are examples of the Beast as Cyborg, the man-made monster. The fear of the cyborg also incorporates the Uncanny Valley—the monstrosity of the replicant is in its almost humanity but not quite. Just off enough to be off-putting.

Beast monsters are supernatural; robot ones are unnatural. I have a vague notion, too, that our fear of undead monsters (zombies, vampires, and the like) have to do with this fear of the unnatural. It ain’t right, and it’s creepy. What do you think?

In Our Readings This Week

Hyde is a monster because he is the distilled, separated “beast” half of Jekyll. He has none of Jekyll’s civilized restraint or rational choice of behavior, therefore he unsettles everyone he meets even before they know he’s a murderer. He represents (actually, he is) everything Jekyll despises about himself, everything humans do that is bad according to Victorian English society.

Mr. Dark (a yellow-eyed, pockmarked vampire himself) heads a whole sideshow circus out of monsters he has created out of human fears. The Witch, Dwarf, Mr. Electrico and the rest all used to be “normal” humans integrated with their inner darks, but Mr. Dark takes each person’s neurosis and transforms the person into a physical metaphor of that neurosis. In a way, Mr. Dark has refined what Dr. Jekyll clumsily tried. And what exactly are the “autumn people?”

Darth Maul, with his red-and-black facial tattoos, horns, black cloak, and menacing yellow teeth, was obviously designed with old illustrations of the Devil in mind: Maul the monster in this case is the less powerful villain: “the monster who terrifies, who gets what he wants through brute strength and violence.”[7]

…ENDNOTES

[1] This is from The Fly, right? Is it also older than this, or is that it?

[2] Angela Carter, from “The Company of Wolves” in The Bloody Chamber.

[3] Marina Warner, in From the Beast to the Blonde, New York, Noonday Press, 1996.

[4] Grover Monster as Super Grover, Sesame Street, the place where live the biggest population of friendly and cute monsters in the world.

[5] From the Beast to the Blonde again

[6] Warner’s phrase—love it! You will be assimilated…

[7] Shanti Fader, from “In Sheep’s Clothing: the face of evil in the Phantom Menace.” Parabola Winter 1999,p. 88-91.

THE FAIR-FACED VILLAIN

The readings/viewings this week were: the play Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Christopher Hampton (as well as the 1988 movie version, Dangerous Liaisons), Star Wars: the Phantom Menace, and of course we revisited our previous readings: the classic Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury, as well as short critical/analytical pieces and some folktales, such as “Bluebeard.”

Meet it is I set it down, that one may smile, and smile, and be a villain.[1]

When confronted with a Darth Maul, we know instinctively that this is something to be shunned, and depending on the circumstances and our character we either flee or fight it. But how do we fight a Darth Sidious; how do we fight the evil that seduces rather than threatens us? In many ways, the wolves in sheep’s clothing are far more dangerous than obvious foes—their work can be done quietly, unnoticed and unchecked. The knight with the shining sword may take down dragons, but is helpless against the rot eating away at the castle’s foundation. A different sort of hero is required for this foe, for it is a completely different battle.[2]

The Fair-Faced Villain is much harder to detect than the Monster. There is no ugly face, no bestial behavior (at least not that you see, until maybe it’s too late). So how does a poor hero vanquish such a foe, let alone even find him?

The Vicomte de Valmont feels invincible, and so does his partner in crime, the Marquise de Merteuil. The evils they do are about domination—sexual, financial, social power. Merteuil puts it best when she asks poor Cecile about her rape. Well, it wasn’t really a rape, was it? she says, I mean did he force you? Did he threaten you and tie you up? No, responds Cecile. It’s just that “he has a way of putting things, you just can’t think of an answer.”

Merteuil has the same talent for domination, and she describes it to Valmont thus: “When I want a man, I have him; when he wants to tell, he finds he can’t. That’s the whole story.” Until the Vicomte falls prey to the one flaw he never imagined would happen to him: he actually falls in love, truly, which (as any of us know who have been in love) makes masks impossible. Once the Fair-Faced Villain’s façade is removed, the villain is no longer powerful. Hence, Valmont dies in a lover’s duel.

In the 1988 film Dangerous Liaisons, Merteuil is de-masked by a large audience: a big group of heroes who spot the crack in her façade, point it out loudly and publicly. Now, as you’ll recall, at the end of the play version our evil Marquise is still going along the way she always has, the villainess not even overtly affected by Valmont’s death. Only the image of the guillotine shadowing her closing lines give us any inkling her days as a Fair-Faced Villain are numbered. This is why I have selected the 1988 movie version of this play for us to watch: the ending is very different than the play, but it’s such a vivid metaphor of the Fair-Faced Villain’s demise. The Academy Awards clip of Glenn Close’s Merteuil silently wiping off her makeup shows physically the metaphor of the dissipated power of the de-masking—you can see her cool smile dissolving even as her lipstick smears.

The Monster is like a mugger: you hand over your money, flee or fight him, then call the police with a description. The Fair-Faced Villain is like a con artist: once you realize you’ve given her your money, there’s nothing to say to the police. Herein lies the special danger of the Fair-Faced Villain: like Iago in Othello or Palpatine in Star Wars, the hero often doesn’t realize the villain is a villain at all until it’s too late.

But every Fair-Faced Villain has a crack in the façade—a fatal flaw in the mask. If a hero can find it, tear away the mask, and expose the wolf under the sheepskin, then the Fair-Faced Villain can be vanquished.

…ENDNOTES

[1] Shakespeare, Hamlet

[2] Shanti Fader, from “In Sheep’s Clothing: the face of evil in the Phantom Menace.” Parabola Winter 1999,p. 88-91.

THE VILLAIN WITHIN

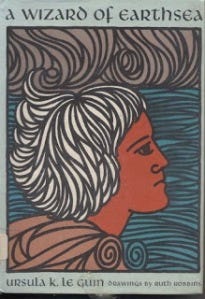

Readings/viewings for this week of class included A Wizard of Earthsea by LeGuin, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde again, and the movie Fight Club. The Palahniuk novel Fight Club was optional.

I have seen the enemy and it is us.[1]

Ged had neither lost nor won but, naming the shadow of his death with his own name, had made himself whole: a man who, knowing his whole true self, cannot be used or possessed by any power other than himself, and whose life therefore is lived for life’s sake and never in the service of ruin, or pain, or hatred, or the dark.[2]

The first rule of Fight Club is: you don’t talk about Fight Club.[3]

Coming to terms with the villain within is not easy and never pleasant. Who, after all, wants to admit they have villainous tendencies? Dr. Jekyll couldn’t bear the fact that he, respectable though he was, actually enjoyed “indulgences,” as he so delicately put it. It bothered Jekyll when he considered “that strong sense of man’s double being, which must at times come in upon and overwhelm the mind of every thinking creature.”[4] It bothered him so much that he used his scientific brilliance to actually separate his inner bad guy, never imagining Hyde would be uncontrollable and end up dominating his “host.” What moral is this story supposed to teach? That to separate the villain within is to destroy oneself? Certainly Jekyll’s distaste at his own sinful behavior isn’t worth dying for in the end, not to mention the murder Hyde commits as well. So the proper place for the Hyde in all of us is integrated within ourselves, not repressed or destroyed, is that the lesson here? And who is the “good guy” in this story—the dreary Utterson, who never seems to do anything fun?

Ged, in A Wizard of Earthsea, also has an artificially separated inner shadow to contend with. Unlike Dr. Jekyll, Ged does not purposely loose the shadow, nor does he seem to know what it is until the climax of the book, when we are in Vetch’s POV and hear the name he finally utters. Unlike the Victorian Jekyll and Hyde who can’t survive in the same world for long, Ged opens his arms and literally embraces his shadow, accepting it as an integral part of him, naming it with his own name and making himself into a whole person by doing so. Hey, but isn’t that the same lesson we learn from Jekyll and Hyde? Hm…

Jekyll’s struggle and demise epitomizes the Victorian Christian conflict: propriety vs. pleasure. Ged’s solution is more Zen-like: accepting the shadow as a natural and inseparable part of his being.

And what about Fight Club‘s Narrator and Tyler Durden? Like Mr. Hyde, Tyler is destroyed at the end, out of necessity. But is he really gone for good? What does he represent in the Narrator? Interesting premise: my husband* has a theory that the Narrator actually dies on the airplane at the beginning, and the resulting story is his death-dream of sorts. Anyone feeling ambitious and has read the book this week? Have anything to add?

*Now my ex. This was a long time ago, wow…

…ENDNOTES

[1] This is originally from comic series Pogo. I don’t have a proper citation for it, sorry.

[2] Ursula K. LeGuin, A Wizard of Earthsea.

[3] It’s a quote from Fight Club. But I’m not supposed to talk about it.

[4] Robert Louis Stevenson, The Strange Story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

SIDE NOTE: I wrote all these before I had read the Harry Potter series. It was that long ago. I don’t want to add those characters or literary analyses into these lecturettes now, because I want to begin to take attention away from a literary work that was made by a bigot. But if you’re wondering why Voldemort or Snape don’t appear here, that’s why. Where would you put them, if you wanted to add them to this villain pantheon? I also taught a whole course for this same program all on Harry Potter, but. No, I don’t have those lecturettes easily to hand, and to be honest, I don’t really feel like searching for them. I can maybe put up the Lord of the Rings course lecturettes, though—I do have those. What do you think? Sound interesting? Let me know.