It’s funny—when I was a kid and even into my teens, to be into Lord of the Rings was a surefire way to get bullied. But now, there are so many fantastic scholars and content-makers across pop culture platforms surrounding the fandom and even deep-dive analysis of LOTR, especially the original “canon” literature. Back in 2004 when this DU class was held, there still weren’t many of these thinkers around, and to be a scholar that covered anything resembling genre literature or :gasp: pop culture, was still pretty rare. A couple of us old-school nerds left over from the ‘70s, etc. were still talking about it, but it wasn’t until the Jackson blockbusters came out that LOTR became a mainstream and widespread part of popular culture again. Interesting to see how my scholarly musings in the form of these lecturettes do (or don’t?) fit in to the current robust conversation.

The week this lecturette would have appeared in class, students would have read through the intro materials I talked about last week, as well as The Hobbit and Fellowship of the Ring. Also, do keep in mind that the Jackson movies were still very fresh at this time, (one still might have been only in theatres? I have to look that up), also that this was a literature course. These lecturettes and conversations, therefore, are centered around the books almost exclusively, though here and there you’ll find a comparison to or a mention of the films.

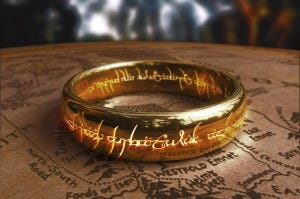

Temptation and the Ring of Power

2004 Hobbits & Heroes

“For where am I to go? And by what shall I steer? What is to be my quest? Bilbo went to find a treasure, there and back again; but I go to lose one, and not return, as far as I can see.”

The One Ring of Power is the center of all the action in The Lord of the Rings. Made by the Dark Lord, Sauron, it contains a good part of his power. With it, Sauron could enslave the known world (or so Gandalf claims). The only way to ensure this does not happen is to destroy it. Of course, being a “magic” ring, it’s no small feat: a volcano in the heart of Mordor is the only place wherein the Ring would actually melt—all other earthly fire doesn’t cut it.

Also, being a “magic” ring, it passes from hand to hand with a force seemingly of its own. The One Ring is perhaps the central character of the story—witness Gandalf’s talk about it in the beginning of Fellowship: he speaks of it choosing to be found, it slipping off Isildur’s finger at an opportune moment, it realizing it would not ever be out in the world again if it stayed with Gollum. The Ring, it seems, has a will of its own, which adheres to the will of any being who wields it: Frodo cannot throw it into his hearth fire, even after he has just heard from Gandalf the scope of its evil. It acts on the spirit as an addiction, and its movements from person to person has everything to do with temptation and desire for power.

The first we hear of the Ring’s real properties is in The Fellowship of the Ring; Gandalf returns to Frodo after Bilbo’s disappearance and explains his discovery. The story of the One Ring’s movements begins with Isildur, heir to the man that helped defeat Sauron, taking the Ring from the battlefield and wielding it against Sauron, later dying in a river when the Ring (by accident or design) fell from his finger, rendering him visible to orcs. Did the Ring choose to betray Isildur? It certainly seems as though it chooses its own movements to an extent—perhaps just the evil will that Sauron left in it makes it have its own momentum.

What does the Ring do to an immortal?

Gandalf says, “Don’t tempt me!” when offered the Ring, and tries his best not to touch it. He knows his wish would be to use it for pity—for using its strength to help the weak. Galadriel, too, imagines the powerful good she would possess if she wielded the Ring, then in her rapture describes the terrifying queen she would become. Wryly, she realizes she has “passed the test,” and refuses it, even though its destruction means the fading of Lothlorien and the power of her own Ring. Tom Bombadil, claims Gandalf, would forget about it, throw it away carelessly, to let it be found by anyone (more on the mystery of Tom Bombadil in the discussion board this week).*

In other words, an immortal (Elf or Dwarf or Istari [wizard]) would soon become a second Sauron. In fact, Sauron is himself an Istari (the Maiar, or demi-gods of Middle-earth), just like Gandalf. We can see, therefore, exactly what would become of Gandalf if the Ring got hold of him. Galadriel saw the terrible power possible in her when she encountered the Ring-Bearer for the first time. Both these immortals, because they are wise and good, leave the Ring alone. We do not come across a Dwarf in the Ring’s throes—as immortals younger than Elves and in love with gold, we can only assume the fate for a Dwarf under the Ring’s spell would be similar to that of an Elf, but this particular temptation does not occur in the epic. Perhaps Dwarves are just too bluff and hard-headed, eh?

*Hey, since I don’t have a salvage of the old discussion boards from this class, wanna treat the comments as a DB and chat about Tom Bombadil? Like, what the heck is up with him? Who/what is he? Knock yourselves out.

What does the Ring do to a mortal?

Men (humans) and hobbits are the mortal races on Middle-earth, and hobbits, it seems, have much longer life-spans than Men. Gandalf tells Frodo in no uncertain terms what happens to humans under the Ring’s power: they cannot die, as is natural; they fade, becoming permanently invisible, and become slaves of the Ring: Ring-Wraiths. The nine kings of Men (no doubt heroic dudes in their day) who possessed the Nine Mortal Rings, came under the power of the One, and what has happened to them? Why, they’re snuffling, shrieking Black Riders now, slaves to Sauron but more importantly, slaves to the Ring Frodo carries.

So why isn’t Gollum a Ring-Wraith?

What does the Ring do to a hobbit?

When Smeagol the hobbit-ancestor comes across the Ring, he murders his friend to possess it. Wielding it too often, he degenerates into Gollum, living far too long and ending up twisted beyond recognition as a hobbit of any kind. Gollum acts like an addict: he thinks about his “precious” constantly, talking to it; he can’t wear it very often but cannot leave it alone either; as Gandalf says, “he hated it and loved it, as he hated and loved himself.” More accurate than the multiple-personality portrayal done so beautifully in the recent films, is I think Gollum’s utter and complete addiction to the Ring. Everything else stems from this. The only reason Gollum is not a wraith is that hobbits are notoriously (and surprisingly to some) remarkably tough and resilient. The only reason he is still alive is the Ring, and it says much that the good folk who come across Gollum do not kill him (Bilbo does not out of pity, Gandalf does not out of a hunch), because his fate is connected directly to the Ring. We will see in the later books just how much the Gollum-Ring connection is essential to the success of Frodo’s quest.

“A Ring of Power looks after itself, Frodo. It may slip off treacherously, but its keeper never abandons it. At most he plays with the idea of handing it on to someone else’s care—and that only at an early stage, when it first begins to grip. But as far as I know Bilbo alone in history has ever gone beyond playing, and really done it. He needed all my help, too. And even so he would never have just forsaken it, or cast it aside. It was not Gollum, Frodo, but the Ring itself that decided things. The Ring left him.”

So claims Gandalf the Wise. Therefore, the Ring’s objective through this story is to find its maker, its master, and woe be to any who comes in its way. And our understanding of the characters we meet along the way comes directly from how they react to the temptation of the Ring. Look at how Gandalf and Galadriel react to it, look at Boromir’s and then Faramir’s decisions regarding it. This is a huge flaw of the films’ portrayal of Faramir, I say, and an awful way to treat that character. He’s not just another Boromir that happens to not fall quite as far, or is able to change his mind or whatever the screenwriters were thinking; Faramir is purer of heart to begin with—he’s never once tempted by the Ring, as his brother was.

Look at Frodo along his quest, watch him crumble under its influence, then look at the wretched, centuries-old Gollum, following him. Those who are not tempted by such an “easy out” to power, or those who are tempted and resist, have the stuff of heroes in them, and those who give themselves to it, lose themselves utterly.

I always presumed that Bombadill was a maiar that was not an ishtari. Per The Simillarion, that is possible.