aka Lidsville

There’s something therapeutic about beginning one’s day by throwing things at a group of youngsters.

In this case, the kids are in their very late teens to early twenties. Most hover around 19-20ish, and all are theatre students of some kind. For example, at Metro, there’s BFAs in musical theatre and tech, and a robust BA which requires at least a minor in something else to graduate. These kids are getting a good education. At times, they even get good training. Which is where I come in.

The class I’m talking about is called Stage Movement, which is the original director’s cut of a seminar/workshop series I’m attempting to shill to corporate folks these days. But it started here in my college courses. It’s basically 16 weeks’ worth of learning manifold ways of creating character with physicality.

See, pretty much all college or university-level theatre programs are designed around Realism as a style—the psychological delvings that these days are the results of a game of Operator from techniques created by a theatre revolutionary from the late 1800s: Konstantin Stanislavski. He was the head of the Moscow Arts Theatre back in that day, and is still known as the grandfather of Realism in theatre. He used the nascent science of psychoanalysis, added a dash of Jungian subconscious studies, and created a way of acting that involved lots and lots of inner character work. In a theatre that suddenly included characters that didn’t say what they were thinking aloud, surrounded by a real-looking set, it was suddenly up to the actors (with the director to guide them) to create the rich inner life of the character without the playwright having written it all out for them to speak. They would suddenly need to pack rehearsals with all the character back story so it would come out in the performance, since not spoken out loud. A few decades later, this would morph into the Actors’ Studio trainings and other high level programs that devolved into Method, or evolved into Naturalism.

As you can probably surmise from this, my Stage Movement teachings are wildly different than pretty much every other technique class an acting student will take. Instead of starting from the inside and then going out, as in psychological Realism, we start on the outside with posture, gesture, movement, and see what inner life that body work brings forth. It’s the difference between outside-in and inside-out acting, which is how theatre people describe it. Starting with the body is way more my jam—I’ve been trained in Realism (inside-out), as all modern acting students are, and so I’m pretty decent at it, but outside-in acting is so much easier for me, and I’m way way better at it (just ask those audiences in the park in Olympia who saw my Feste this past summer). I love to teach physical acting and physical character building because of my own inherent jiving with it. But how do I teach it?

I have a really big tool kit of exercises that I’ve used for various lessons in this field—being a lifelong student of theatre and the child of a dancer, I’ve spent many years gathering sticks, twigs, and bits of fluff to make a solid bird’s nest of course curriculum. I use dance and martial arts conditioning exercises; breath work from singing, meditation, Skinner releasing, and yoga; energy dynamics from yoga, kenjutsu, and Lessac; and precision and mechanics from Alexander, Grotowski, kinesiology, modern dance, and clowning. All of these things touch on various aspects of how to control one’s body and how to make it do really cool things. Like become a different person.

One of my favorite exercises of all of these myriad practices is creating tableaux vivants. These are so much fun, and more: they teach these young cyberkids where their bodies are in space, what negative space is, stage picture, perspective, balance, stillness, etc. Plus, I like to think I’m being an oldey-timey art teacher: asking them to exactly and precisely replicate a master’s work of art.

Despite what many people might think, copying masterworks as exactly as possible is a great way to become an original master oneself. Performing arts are absolutely included in this truth—young actors should imitate the performers they like best while they’re in training, in order to learn the craft, build skillsets, and eventually have the tools to cultivate their own personal style. Writers too. I have pontificated on the topics of originality, technique, and discipline in the performing arts a few times already here, when talking about Aesthetics and why you should Actually, Don’t. It’s, shall we say, a topic on which I have some strong opinions. But back to tableaux.

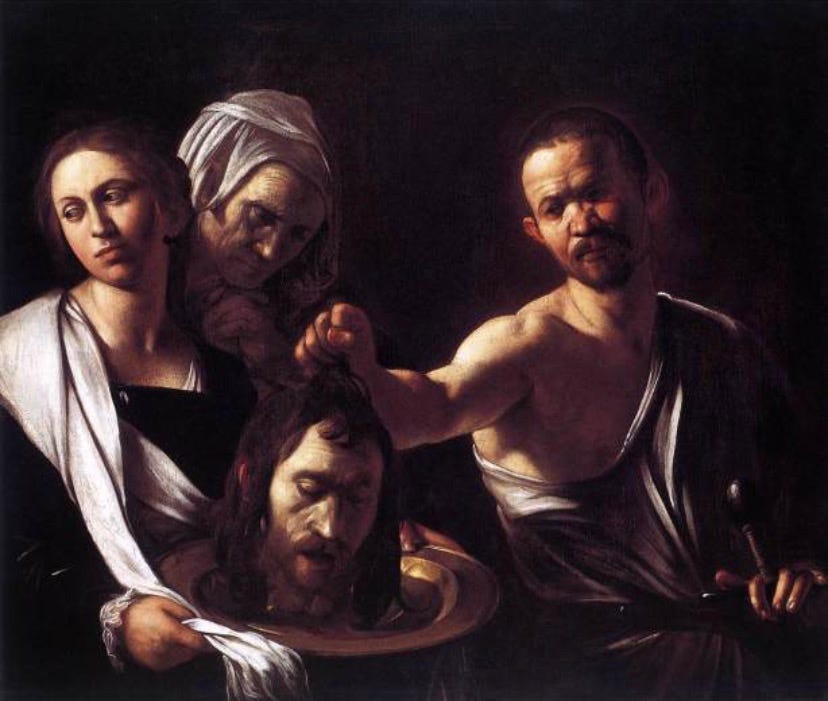

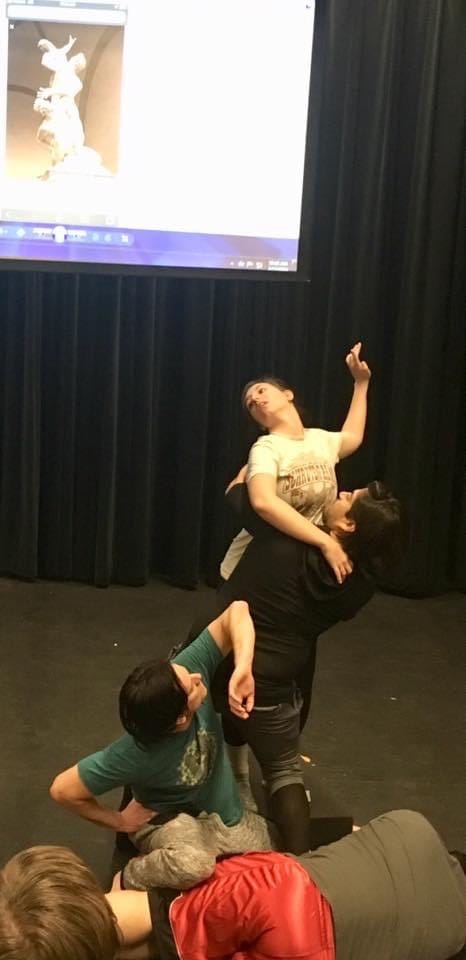

I’m constantly impressed, each time I teach the tableaux vivants unit, by the students’ choices of masterwork to portray. I leave it up to them, maybe show them images of past classes and a marvelous Italian troupe that specializes in Caravaggios, and then they have at it.

Oh, I realize you may not know what a tableau is. Well the simplest description is: a group of performers arrange their bodies in such a way as to replicate exactly a work of visual art. A couple scarves and maybe a chair can be involved, but for the most part, what they’re doing is recreating in exact detail a work of art using only their physicality. A tableau vivant is a ‘living picture,’ then, if that makes sense. Here’s an example:

So it’s great training for them: they need to get the “camera” angles right, the positioning of their bodies down to the last pinkie finger just so, even facial expressions need to be correct. And then they need to hold it (these classes move into position, snap into it, and hold for a count of 5). It’s the perfect combination of an intellectual and a physical exercise—it’s such a test of precision, coordination, and of course collaboration. Any theatre exercise or practice teaches the fine human art of collaboration, more than any other field I’ve known. But. Tableaux in particular do this really well, especially when the students hear I’m grading them based on their exactitude, taking points off for their smallest inaccuracies.* It lights a fire under them and makes them pay far closer attention than they might in a modern acting piece where they can be a little muddy and still pull it off. There’s no approximations in a tableau vivant—it either works or it doesn’t, and it works because it’s exact.

*Okay so sshh don’t tell anyone, but I don’t actually grade them this strictly. I don’t take points off for inaccuracies, but I do grade them based on how well they work together and the overall effect of the tableaux in performance. I *tell* them I’m going to grade them this savagely, though, because it gets them doing fine detail work they rarely do in other theatre classes. They end up showing a far better final product because of this benign lie I tell. They also lift up their fellow group members that maybe are falling short much more than they normally would, because they think each one of their grades will be affected by one guy dropping the ball. I feel okay about deceiving them like this, I really do. The final results are worth it, I mean look at this:

Oh but yeah, about the subtitle of this post (besides it being a reference to the surreally bizarre Sid & Marty Krofft kids’ show from the ‘70s):

I curate all warmups for these classes precisely, to align with all the movements and techniques I know they’ll have to use during the session. You can see how important warmups are to me, if you look at my book—each section of techniques begins with a whole subsection of what warmups to do before tackling them. Normally in a college level Stage Movement course, the students learn a long list of locomotor movements the week before the tableaux unit, and so I incorporate those with the precision they soon need to use for them, in a dodge game.

When the ex and I headed a martial arts school, way back before I was a college prof, we did this one warmup for our adult and kid martial arts students alike. We collected plastic lids from food containers—you know, cream cheese, yogurt, Country Crock fake butter, Pringles… smallish plastic lids that vary in size depending on the tub. We ended up with a bag full of safe approximations of ninja stars: the plastic lids fly like small frisbees when thrown, and don’t hurt at all when you’re hit by them.

Unlike the primal and savage (and potentially dangerous) traditional game of dodgeball, however, working with the lids requires a heckuva lot more precision in movement, both in attempting to dodge, and to catch, the slim plastic fliers. And I add all sorts of fitness and other movement rules to the game, in order to tie the curriculum together. So.

Point is, during Stage Movement class, I often begin my day by throwing things at young people, and it feels fine. It feels just fine.

What? They get warmed up enough to later contort themselves into classical art poses, and that’s good enough for me. And them.

Nice work if you can get it. Though it doesn’t pay…