A couple things are bugging me about a recent comparison (and older ones now I’ve looked at the recent one) between the two best detectives in our collective fictional universe. These comparative writers are missing (or misinterpreting) a vital aspect of Sherlock Holmes’ MO and character.

Is this another nerdy rant? It is. Let me explain:

The concept of whether Columbo [is] America’s Sherlock has been written about quite a bit since the lockdown trend of Columbo re-watching, in particular. Since so many people turned to Columbo to soothe stress levels during the hardest times of the pandemic, naturally a bunch of these isolated thinkers and bloggers have taken to the internet to suss out why. I think, too, the Sherlock/Columbo comparisons have much to do with the ginormous success of BBC’s Sherlock series, with its rabid fans and modern interpretation of an old icon. Columbo (thankfully?) hasn’t gotten the remake treatment, [1] and so the old reliable is what we’ve got. And, like the Lieutenant’s old reliable, his beloved Peugeot, it may be old, but it’s still going strong.

The center of what’s bugging me about some of these comparisons between Sherlock Holmes and Frank [2] Columbo is on these writers’ assertion that Columbo is humble, lower-class, and deferential, while Holmes is snooty, upper-class, and a snob to everyone, especially the police. This couldn’t be more untrue about Sherlock Holmes, and it makes me think, frustratedly, that the version of Sherlock that these critics are talking about is only the one played in the 20-teens by Benedict Cumberbatch. The OG character of Holmes—the Sherlock from the books, the character invented by Arthur Conan Doyle, isn’t very different from Columbo at all, as Victorian English as he is.

How is this true? I’ll explain. Ahem:

SherloCop

Sherlock Holmes is actually quite humble & self-effacing in the presence of police: he famously gives the official police all the credit in most of his cases, for one thing, and he always shares the clues he finds with the police, or he leaves some evidence behind for them. I’m thinking in particular about “The Devil’s Foot”—he not only leaves half the evidence behind, but he instructs the vicar to give the police “his compliments” and says he’ll help them in any way they might need. That they don’t take him up on his offer isn’t anything to do with him snubbing them (quite the opposite, it seems).

Holmes recognizes the necessity for the official police, and even in those cases where he solves it alone, or acts on his own conclusions about the culprit, he doesn’t insult the official force to their face, nor does he ignore them or leave them out of the case completely. In The Valley of Fear, he reassures the officials he’s working with that if he ever does separate himself from official police investigation, it’s because they’ve separated themselves first. He even shows overt admiration for some of the better officials he’s involved with, such as Inspector Gregory in “Silver Blaze,” and both inspectors he works with closely (MacDonald and Mason) in Valley of Fear get his well-deserved respect, albeit sometimes with a touch of mentor-like correction. But the reason he even bothers with such instruction is because he respects their skills, lower level than his though they may be.

And he’s transparent in his methods: he tells officials that he’ll hold back his theories only as long as he needs to, only long enough until he gathers all his evidence. Sometimes, as in A Study in Scarlet, he’ll tell them that they can work their case the way they see fit, and he’ll work it in his way. At the end, though, he still reveals all his evidence and conclusions, and gives them all the credit. It’s Watson that takes it upon himself to publish his accounts of what Holmes does in these investigations–that’s the only reason anyone knows that Holmes was ever involved. It’s only Watson’s writings that reveal Holmes as the real galaxy brain behind these cases. If Watson weren’t around, nobody would ever know about him.[3] Even then, the police often misunderstand or underestimate Holmes’ prowess, like Detective Forbes from “The Naval Treaty:”

“I’ve heard of your methods before now, Mr. Holmes,” said [Forbes], tartly. “You are ready enough to use all the information that the police can lay at your disposal, and then you try to finish the case yourself and bring discredit on them.”

“On the contrary,” said Holmes, “out of my last fifty-three cases my name has only appeared in four, and the police have had all the credit in forty-nine. I don’t blame you for not knowing this, for you are young and inexperienced, but if you wish to get on in your new duties you will work with me and not against me.”

Now, Holmes might have a quip or two for Watson in private about an official policeman’s stubborn dullness or ineptitude, but he won’t usually say any of that to their face. Lestrade is an exception, but even then, Holmes’ disdain is couched in friendly ribbing. In fact, if you look at his attitude toward Lestrade in “The Norwood Builder,” you can see that Lestrade is a real dick to Holmes throughout, until the end where Holmes finally pieces the case together. At that point, Lestrade exasperatedly demands why Holmes needed to be so dramatic, when Holmes replies basically: You gave me some shit earlier so I gave you some back—by the way, congratulations! Here’s all the evidence, don’t include me in any of your reports.

Lestrade, as I said before, is an exception: he seems to be the one official that is something of a buddy, as we can see in his beautiful speech at the end of “Six Napoleons”:

“Well,” said Lestrade, “I’ve seen you handle a good many cases, Mr. Holmes, but I don’t know that I ever knew a more workmanlike one than that. We’re not jealous of you at Scotland Yard. No, sir, we are very proud of you, and if you come down to-morrow there’s not a man, from the oldest inspector to the youngest constable, who wouldn’t be glad to shake you by the hand.” [4]

In other words, though Holmes is not an official cop himself, he works closely with the police and values their necessity.

Snotlock Holmes

What about Holmes’ snooty snobbery?

What snobbery? For one thing, Holmes is an expert in disguises, and disguises are literally all about the ability to self-efface. Holmes lowers his own status and elevates others’ (especially official police) all the time. This is central to Columbo’s MO, but Holmes is excellent at it.

By donning a disguise, Holmes is Columbo-ing—that is, meeting his interviewee where he is. That’s what sets Columbo apart from his hardened noir predecessors, as well as his gritty 1970s contemporaries: he’s scruffy and unkempt, sure. He’s also low-status, and homey, and sincere.[5] But so is Sherlock Holmes. Holmes isn’t above throwing himself down into the mud to the scoffing of official police (“Boscombe Valley Mystery”); or becoming a drunken groom (“Scandal in Bohemia”) or seedy sea captain (several stories, including “Black Peter”); or pretending to swoon and be mentally ill, to the mocking of the aristocrats that only he suspects (“Reigate Squires”); or seeming distracted and confused, to the disdain of high-status horse-owner Colonel Ross (“Silver Blaze”), monologuing randomly about roses and religion (“Naval Treaty”); and on and on.

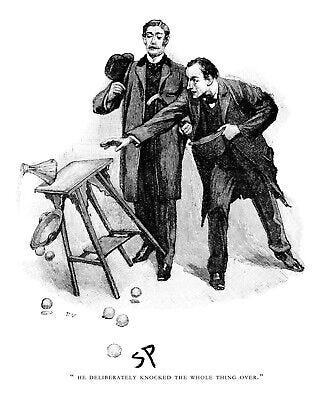

Actually those last are the most Columbo-ish things Holmes does, though he does a lot more: he doesn’t bother to correct anyone who denigrates him, calls him a scatterbrain, or underestimates him (or wonders aloud what all the hype about him was about). He doesn’t try to explain to a scoffing gent or impatient official when he uses unusual evidence-gathering techniques, or when he does things like spill water over a suspect’s shoes or knocks over a table of oranges—he lets whoever is underestimating him go on doing that, while he zeroes in for the kill, the often-dramatic “gotcha.” Can’t get more Columbo than that.

We see over and over again how good Holmes is at meeting people where they are, or giving them what they expect. Not only does he *not* let the high and mighty intimidate him (nor does he assume their innocence),[6] he doesn’t turn his nose up at the humble, either. Both of these dynamics are what makes Columbo tick, but Holmes was a master at them first.

Detective, Drama Queen

Here’s some more examples of similar behavior in Holmes and Columbo: these events show how much each character loves being theatrical, and how each finds himself in the middle of (or creates) drama because of this.

The scene at the mission in “Negative Reaction” is one that comes to mind immediately: Columbo has had a long, rough night, and finds himself mistaken for a homeless man down on his luck by a well-meaning nun—she ends up, wide-eyed, asking if he’s under cover, as his “disguise” is so good. In Columbo’s case, it’s not really a disguise (Holmes would have worn an excellent one, as he does in “Scandal,” in order to get gossip, and ends up witnessing Adler’s wedding), but the ease with which each man moves between roles as needed to gather evidence, is very similar.

Holmes’ sea captain character that he portrays in several stories (Captain Basil) functions much like Columbo’s stories about his family or his wife—it’s a way both men become exactly what the person they're talking to needs, to loosen up and let their guard down. Neither detective is afraid to humble himself, in front of anyone.

Watson tells us multiple times that Holmes has a peculiar warmth when dealing with women. Columbo’s warmth and kindness in “Murder by the Book” as he takes Mrs. Ferris away from the upsetting crime scene and makes her an omelet is right in this vein.

Holmes’ theatrical setups like the goose guy in “Blue Carbuncle” are very Columbo. Remember that scene? Holmes notices the goose seller is big into gambling, and isn’t willing to give him any info, so he just jumps right in and pretends he’s got a bet on, sucking him right in. Columbo does this sort of thing all the time—one scene that pops into my head first is the end of “Bye-Bye Sky High” when Columbo waxes rhapsodic about that brilliant Danziger’s theory of the murder. The murderer walks right into the trap of confession. Or, even more vividly: Columbo staging the reverse photograph and pretending to have destroyed the original. Dick Van Dyke’s murderer character can’t *not* give in and supply the information–the trap is too good, too exactly what the character is about.

Dramatic gotchas like the clock chime setup in “Crucial Game” or the glove reveal in “Suitable for Framing” are very Sherlockian. Think about the dish uncovering reveal in “Naval Treaty.” It’s just like Columbo’s glove reveal. [7]

I can think of a bunch more comparisons–give me some of yours in the comments, yeah?

Watson himself does get irritated by what he calls Holmes’ unfeelingness, even arrogance, but that’s because he gets the brunt of it. Holmes doesn’t express any of that to his suspects or to the official police, at least not usually. Watson is also the only person who gets to see Holmes’ rare cracks in the armor. Columbo’s cracks in his armor are also rare.

“It is fortunate for this community that I am not a criminal.”

~ Sherlock Holmes in “The Bruce-Partington Plans”

Both detectives wryly admit to doing crime: planting evidence, allowing a criminal to go free, breaking & entering, entrapment setups, dramatic gotchas, etc. are all ethically questionable things both men do in order to nab their suspect. Or, as in the case of Grace Wheeler or Aunt Edna or or Mrs. Goodland or Leon Sterndale or Captain Croker or John Turner, to let them go. Columbo will put a potato up a tailpipe and plant evidence in the trunk to get a murderer, he’ll show up in the private home of a suspect and touch or even steal property before planting it in a trap (say it with me: “liquid filth!!”), and Holmes will become engaged to a maid so he can sneak into a house and burn blackmail materials.

Holmes will pick a lock to break-and-enter in order to find evidence, and Columbo will stage an elaborate fake suicide to entrap his suspect. The list goes on. In Holmes’ case, his friends in the official police warn him that he’ll get into trouble for this criminal activity one of these days (they also admonish him that well sheesh of course you have more evidence than us–we’re not allowed to get evidence this way). Columbo all but admits to doing unethical things to a criminology class, and a police photographer questions his methods even as he helps him with them: “This is searching without a warrant!” Columbo is no less eccentric and against the grain in his official investigations than the independent investigations of the world’s only “unofficial consulting detective.”

Shlublock Holmes

Holmes is often underestimated by criminals and official police alike, and he doesn’t bother correcting them, as shown above. He doesn’t “always command respect” when he enters a crime scene; far from it. In fact, he’s most often met with irritation from those officials who feel like he’s getting in the way, or that his kookiness isn’t useful. By doing this, he can often fly under his suspects’ radar, too, in a very Columbo-like way: a suspect may go a whole story thinking Holmes has no idea he’s on to him.

I think what’s happening is that modern commentators are getting old fashioned clothing and what would be normal everyday Victorian manners mixed up with an upper classness or aloof snobbery. But Holmes doesn’t have much money, though he comes from country squires. He lives with Watson literally because he can’t afford the rooms at 221B by himself. He’s even described as having Bohemian habits by Watson, and that use of the term Bohemian meant the same thing then as it does today: a sort of hippie-like free living outside of norms and societal constraints, or simply an artistic woo-woo sloppiness (to be fair, Watson also describes himself as having a Bohemian disposition).

Watson is a downtrodden ex-soldier, Holmes a stoned Bohemian. They’re neither of them snooty. Holmes, in fact, is arguably just as seedy as Columbo, if you go by the appearance of his apartment and not his own clothing. He’s got “cat-like” personal grooming, [9] but his slovenly treatment of his shared home crosses the line for even rough-and-tumble Watson, as he tells us at the beginning of “The Musgrave Ritual:”

An anomaly which often struck me in the character of my friend Sherlock Holmes was that, although in his methods of thought he was the neatest and most methodical of mankind, and although also he affected a certain quiet primness of dress, he was none the less in his personal habits one of the most untidy men that ever drove a fellow-lodger to distraction. Not that I am in the least conventional in that respect myself. The rough-and-tumble work in Afghanistan, coming on the top of a natural Bohemianism of disposition, has made me rather more lax than befits a medical man. But with me there is a limit, and when I find a man who keeps his cigars in the coal-scuttle, his tobacco in the toe end of a Persian slipper, and his unanswered correspondence transfixed by a jack-knife into the very centre of his wooden mantelpiece, then I begin to give myself virtuous airs.

Okay, I feel like I’ve nerded out and popped off about this long enough. I feel better. How about you? What are your thoughts? Add them to the comments.

[1] Though I do hear that new TV show Poker Face pretty much is.

[2] Yes, nerds, I know: the Columbo creators have insisted that Columbo officially has no first name. I also know the whole story about the erroneous Philip. But I like to honor the prop guys who made the Lieutenant’s ID, and besides, Frank just suits him so well. Yanno?

[3] “Your merits should be publicly recognized. You should publish an account of the case. If you won’t, I will for you.” ~from Study in Scarlet

[4] And it’s established in the beginning of this story that Lestrade tends to pop over to 221B pretty frequently, just for social reasons.

[5] But, like, is he? A strong case can be made for Columbo’s homey shtick being all a persona he puts on (as whip-smart lawyer Leslie Williams points out in “Ransom for a Dead Man,” among several others). It’s really impossible to know, but if you look at one of his angry outbursts (to either Barry Mayfield or Milo Janus), it’s hard to believe his doofy persona is all always totally sincere.

[6] In “The Reigate Squires” (or “Reigate Puzzle”), Holmes takes down the aristocratic culprits, specifically because he doesn’t automatically assume their innocence on account of their social status: “I make a point of never having any prejudices, and of following docilely wherever fact may lead me…”

[7] Holmes goes into detail about this love of the dramatic in novel-length adventure The Valley of Fear:

Holmes laughed. “Watson insists that I am the dramatist in real life,” said he. “Some touch of the artist wells up within me, and calls insistently for a well-staged performance. Surely our profession, Mr. Mac, would be a drab and sordid one if we did not sometimes set the scene so as to glorify our results. The blunt accusation, the brutal tap upon the shoulder—what can one make of such a denouement? But the quick inference, the subtle trap, the clever forecast of coming events, the triumphant vindication of bold theories—are these not the pride and the justification of our life's work?”

[8] I love how Watson is all like “Wha?” in this illustration, but in the narration he catches on right away that Holmes wants him to take responsibility for the deliberate accident, and that there’s method to Holmes’ calculated sloppiness.

[9] This is an observation of Watson’s from Hound of the Baskervilles, and is one of those places where the difference in cultural norms is so different in Victorian England vs.1970s LA. Classism and class presentation was very different back then, and over there. Looking personally shlubby wouldn’t have been nearly as possible or acceptable for Holmes in normal English society, but then it can be argued that Columbo’s sloppiness is also not really socially acceptable in his environment either.