Realism (part 1)

A simple vocab word that’s the center of a major artistic beef I’ve had for many years, that’s only irking me more as time goes by.

The following rant is based on a (solo) panel presentation given at Page 23’s online LitCon in 2020. Adapted for today’s… /gestures widely/. I talked a bunch and I had cool purple-bordered powerpoint slides, so what I’ve done is to use each slide title as article subtitles here, and will likely use some if not all of the images I had on those slides, though I may find more/different ones that have become relevant in the three years since I did this presentation. Oh, and! As I’ve been filling this skeleton out and adding all the relevant info, I’ve noticed it’s gotten a mite bit long. So I’m a gonna do this rant in two parts. The first is here, called REALISM. Next week, stay tuned for Part Two, which I’ll call METHOD. Strap in, jokers! On y va…!

OPENING NOTE: I use the word ‘actor’ for anyone who acts. I don’t gender the word into ‘actor’ and ‘actress,’ as the latter is what’s considered the diminutive form of the noun, and, well. As an actor myself, I don’t cotton to being a diminutive version of the ‘real’ thing. So. Don’t get confused by any genders being referred to: here, ‘actor’ means he, she, and they.

Toxic Realism: How ‘Method’ acting is a dangerous jok(er)

Part 1: Realism

Allow me to begin my rant against what I call Toxic Realism with the story of this headline:

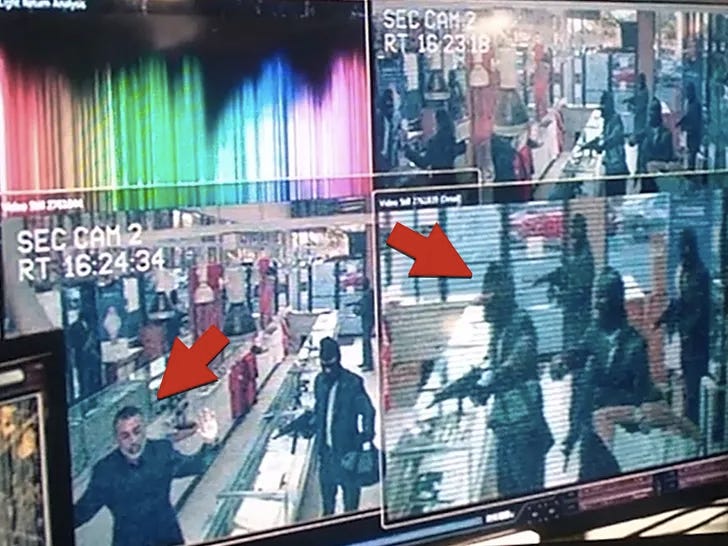

CBS sued over “guerrilla style” robbery scene

Okay, so what happened was: NCIS: New Orleans hired a bunch of actors to do a jewel heist scene in a mall. It was part of whatever crime-of-the-week was needed for that particular episode. The actors, naturally, assumed they’d be doing your basic group scene, and that, as is the safety norm for anything like this, the required permits were in place, police and other security personnel were notified and recruited to help with safety protocols, and the mall would be populated by extras.

Yeah, no.

Instead, nobody was notified, they were instructed to do the scene as they would (i.e. with ski masks on and realistic-looking prop firearms), having not only not notified the local authorities, security, and nearby businesses, but just…had them enact a robbery. In public. (like: WHAT)

And so what happened was exactly what you might expect: the real police with their real guns appeared on the scene; bystanders and businesses were scared and traumatized, and CBS ended up being sued. Thank god nobody was hurt: this happened in 2020, and can you imagine a police officer rushing into a mall, having received a panicked active shooter call, and seeing this robbery taking place? In any case yiiiiiiikes can you imagine what could have happened? As it is, CBS was sued, all actors involved were also fricking traumatized and terrified (I mean seriously—can you even imagine?) and this so-called ‘guerilla’ scene-making was never done again.

I would like to pose the question: WHY the HELL did those showrunners assume that doing the scene this way would make it better?? How did any of them think this would go? It was NCIS, too; though a second cousin of the Law & Order type behemoth shows, this one is still pretty far up there in the popular weekly crime business. It couldn't have been a money thing, in other words. What was the point of endangering all these people, in the name of good theatre?

I aver it’s because they thought the scene would look and feel more real.

And there we have the center of Toxic Realism: it creates a dangerous confusion between wanting authenticity (Realism) in your art, and doing something actually for real.

REALISM does not equal REALITY

Authenticity

Ever since the advent of Reality TV, ultra-realism in acting has been falsely equated with excellence. The real-er an actor is, the more likely he is to win accolades, admiration, and even awards (see Joaquin Phoenix’s award-winning success with Joker). This is a problem, and often a dangerous one, especially when it comes to scenes of violence. It’s this addiction to ‘authenticity’ that makes for actors to ditch their craft and hard work training, in favor of a realism so raw that it falls apart.

To Hold, as ‘Twere, the Mirror up to Nature

Where do we get this Toxic Realism idea from? One source that comes to mind is Hamlet’s speech to the Players. This old-school direction still sticks with us, precisely and vividly; though acting in Shakespeare’s time would have seemed much bigger than what we are used to, you can see in what Hamlet instructs that a form of Realism is something we’ve been equating to acting quality for centuries. Thing is, Hamlet is talking about balance. And it’s still a craft—though he doesn’t want his lines shouted like a town crier, the actors still need to be able to project well enough to be heard. Which makes me wonder if the commonness of film today is one of the many causes of today’s ultra-realism addiction. In film acting, you do need to pull reactions and diction and everything else way back. It can be argued that a robust theatrical delivery isn’t relevant training for a film actor, but what about the rest of an actor’s technique? Has this film-acting subtlety been mistaken for lack of craft?

Let’s listen to Hamlet’s instructions. For the entire speech, check out Doctor Who, er, David Tennant’s portrayal below. Actually, I recommend watching the video clip first–as an English and a Theatre professor, I am adamant on the importance of hearing and seeing Shakespeare, before any attempts to read it silently. I’ve clipped a couple bits from the famous speech in a quote below as well. A lot of his direction sounds just like things you’d hear from a modern director, which I find fascinating. It’s too long to excerpt in full text here though, so do watch it, yeah? If Tennant isn’t your bag, baby, pick any other actor you like online and watch them do it. I’ll wait.

Speak the speech, I pray you, as I pronounced it to

you, trippingly on the tongue: but if you mouth it,

as many of your players do, I had as lief the

town-crier spoke my lines. Nor do not saw the air

too much with your hand, thus, but use all gently;

…

Be not too tame neither, but let your own discretion

be your tutor: suit the action to the word, the

word to the action; with this special observance:

That you o'erstep not the modesty of nature:

for anything so o’erdone is from the purpose of playing,

whose end, both at the first and now, was and is,

to hold, as 'twere, the mirror up to nature;

to show Virtue her own feature, Scorn her own image,

and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.

…

O, there be players that I have seen play, and heard others praise,

and that highly, not to speak it profanely, that,

neither having the accent of Christians nor the gait of Christian, pagan, nor man,

have so strutted and bellowed that I have thought

some of nature's journeymen had made men and not made them well,

they imitated humanity so abominably.

But, as I said in my article ”I Do My Own Stunts” (Fight Master Spring 2014), to hold the mirror up to nature isn’t holding up nature. A mirror is a precision instrument, constructed with careful craft, in order to reflect its subject well. I plan on re-remixing this article and the three old blog posts from whence it sprung, here in a week or two. I’m not sure how readily this particular issue of this particular journal is gettable, but let me know if you do so—I’d be happy to discuss. Anyway.

Real(ism) History

The history of ‘Method’ acting has its roots in Stanislavski’s ground-breaking work with the beginnings of Realism in the Moscow Art Theatre, in the late 1800s. This movement towards Realism (playwriting as well as design, which meant actors had to act in a different style to match the scripts) was a reaction to the melodramatic, bombastic style popular at the time.

Psychology was an infant science at this time, too—to come at a character from the inner life, the secrets and workings of their brain, was wildly different than anything actors had done before, Hamlet’s advice notwithstanding. Plus, unlike Shakespeare and others after him, the plays written in a realistic style required this. Characters for the first time didn’t state their objectives aloud, even only to the audience in soliloquies: they hemmed and hawed, lied, talked around topics, etc. just like real people do. Subtext wasn’t a thing before then: it was all spoken in the lines, it was text-text. Suddenly, then, with this new genre, doing ridiculous things like imagining what the character had for breakfast that morning, or what she was doing in the scenes where she doesn’t appear onstage, was often necessary in order to handle the dense, realistic material of Realism.

Later: Pinter and his Pauses

The Actor’s Studio in the mid-20th century and its legacy stretched on through the mistranslation/game of Operator of Stanislavski’s original ideas of Realism, that has gotten more and more ultra-naturalistic, and more importantly, has been central to modern and contemporary acting training ever since. Remember when I talked about outside-in acting training, which was focused on physical and vocal skill, as contrasted with inside-out acting training, which was mainly centered around character objectives and complex psychological work? Realism as a style needs the latter much more than the former–in most contemporary acting training programs even today, the former type of training is usually only tacked on to the latter if a student is interested in entering musical theatre as a career. But before Stanislavski, actors never went through that inside-out process as a rule. Now, it’s the only way most schools teach acting at all, unless they're an advanced specialty school, like Dell’Arte or Cirque du Soleil. Method acting takes the inside-out technique to an extreme, and not one which adheres to either Hamlet’s complaints or Stanislavski’s original idea of what Realism should be as a style.

My Dear Boy, Try Acting

The following story is told to literally every acting student in literally every class they take. It may be apocryphal, but the agreed legend is that it really happened. The story is pithy as a joke, and it goes like this:

During the filming for Marathon Man, a young Dustin Hoffman (one of the earliest and most vocal followers of Method acting) was to enter the scene as his character who has been unable to sleep for a few days. He mentioned to his co-star, Sir Laurence Olivier, that he, like his character, also hadn’t slept for that amount of time. Olivier sighed, and quipped,

“My dear boy, why don’t you just try acting?”

Michael Simkins blames the widespread extreme warping of Stanislavski’s work on Lee Strasburg, which is… fair. Read his take on the above anecdote and more on the pitfalls of Method in this article from The Guardian. He agrees with me largely: that some of the original technique can be effective and helpful, but take it too far and it’s just too much, and becomes unsustainable, especially in live theatre.

Even recently, only a couple years ago, I read an astonished tweet by someone amazed that ScarJo and co-star Adam Driver were able to cry for real onscreen, and also be able to breathe and speak the while. That’s… that’s just training. It’s technique. It’s actually physical technique: breath work and vocal training and such. Do people not know this? Wait. Do people really not know that Reality TV isn’t actually real? Okay put a pin in that one—I’ll talk about that in Part 2.

REALISM does not equal QUALITY

This false equivalency of realism with quality is dangerous—it elevates toxic behavior at best, danger to actors and their surroundings at worst. Leto’s Joker took to extreme a perceived immersion in the character that people say Ledger did. Was this behavior necessary? Did it make Leto’s Joker groundbreaking? (This is an honest question—I haven’t seen Suicide Squad.)(Of course I know the answer. Ssh). Whether or not the intense isolation and character journaling made Ledger’s Joker the phenomenal performance it was is arguable at best, and of course I don’t have reliable information on the circumstances surrounding his death, other than its tragic cause.

But don’t get me started on Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker. I mean, the consensus is that Jared Leto acted like an ass, in an attempt to ‘get into’ his character with a Method intensity, but he was merely disgusting, and his performance didn’t even turn out that great. Joaquin Phoenix, though, was not only an ass, but actually dangerous, both to himself and to others on set. And yet he’s widely lauded for his work on Joker. Don’t get me started. Don’t.

Okay, okay, fine:

Danger, Will Robinson

I have a major problem with Phoenix’s Joker, not the least of which is the fact that he was awarded Best Actor for it. I shall now deconstruct why.

According to multiple sources, including reports from the trenches, er, set of Joker: Phoenix lost about 50 pounds for the role, only spent about 15 minutes on makeup each day (the shortest amount of time on record for any actor who has worn the painted Joker face)* because he couldn’t sit still for longer than that. He improvised a good portion of his lines—how far he followed whatever screenplay there was I’m not sure, but it sounds like he was extempore through most of the shooting. He spent a lot of time isolated away from the myriad other people that were hard at work on this movie, refusing to rehearse at all. And here’s where I get particularly incensed. All the above mark this grown-ass man (and apparently great actor?) as nothing more than a wiggly and self absorbed petulant child. But that last is the kicker. Literally.

*I mean, fricking Cesar Romero refused to shave his mustache! They painted the clown white over it! And even he paid more attention to his Joker face!

Phoenix’s refusal to rehearse includes the fight scenes. He never came to rehearsal for the fight scenes and never learned the choreography created for him by the stunt professionals on this project. Why? You guessed it. That death knell of a word we’ve been talking about: authenticity.

And so the stuntpeople had to just be like, Welp, everyone be careful. We don’t know what he’s going to do and we can expect him to overshoot or otherwise miss his marks.** So just watch out for yourself and also be sure you keep a weather eye out on where he is. And, yanno. Hope for the best.

In any piece of performing art but ESPECIALLY in stunt work, this is in every possible way NOT COOL. In one fight scene, Phoenix apparently came close to injuring some action actors who weren’t professional stuntpeople but were choreographed to just beat his character up. You know, because that’s best for the story. He of course came to no blocking or other rehearsals and so he fought back, repeating savage kicks at the actors who were only trying to do their jobs well, but now had to try and save their own skins on top of it.

**A mark in this case refers to a place where an actor has to stop, in order to be on camera or in the perfect place for an effect or a stunt. One such stunt in Joker was a car accident setup, where he’d stop on his mark where the car was to stop, then the stunt guy would come in and do the dangerous bit of flying up onto the hood and windshield then falling, at which point Phoenix would go back and take over for the reaction shot. If he doesn’t meet his mark on any regular shot, it’s a pain in the ass for all the camera operators, director, and especially cinematographer. But if he misses his mark on this car stunt? …Yeah. But it’s okay, he can’t rehearse because that would make his reactions all fake…

So, let me get this straight: Joaquin Phoenix as the Joker refuses to rehearse any fight scenes with anyone, including the stuntpeople, putting everyone in abject and unnecessary constant danger; during shooting one of same, he attacks non-stunt-trained actors (as well as blatantly disregards the professionals’ choreography); and…what happens?

He gets not fired in disgrace, blacklisted ever after as difficult to work with, but instead is … awarded a Best Actor Oscar? Dafuq?! Make it make sense.

(And another thing: why is it now an accepted thing, since Heath Ledger’s self-subsuming dark take on the character, that anyone who plays the Joker needs to descend into this kind of dangerous personal poison that nears the madness of the Joker himself? It’s a comic book villain, you guys, gritty origin story, reboot, or no.)

My dear Joker, why don’t you try acting?

REALISM is just a STYLE

MY HOT TAKE: a Method Actor is a Lazy Actor

Authentic-seeming realism takes a lot of work. And training in one’s craft, which takes time. Those who resort to ‘Method’ are taking the easy, sloppy, even dangerous way out. Problem is, they’re getting rewarded for it.

Tune in next week to get the rest of this hot tea!

<<Citations to come at the end of Part 2. Spoiler alert: it’s mostly just from my own brain, other than the articles I’ve already linked to in-text. But. I’ve taught enough comp courses that I almost literally can’t help myself. So. Stay tuned for those next week.>>