Fear is the Mime Killer

I was requested, nay, demanded of, by more than one of my readers (hi

), that I need to make my clowning analysis pieces into a triumvirate. Last week, I bought myself some time by writing only clown-adjacent, talking about my tabor and one specific clowning role that I experienced, with that object’s attachment to the practice. I inserted that one into my clowning discourse, because once I started drafting this third in the sort-of trilogy, I got way deeper than I predicted, and so I needed time to sort all this out. So.Here’s the brief (apparently inspirational) paragraph where I mention mimes & my theory of why they’re eerie, from my second clowning deep-dive, on The Fool:

“Related to this concept (along with the Shamanic concepts I introduced in Part 1) is the hatred/fear of mimes. Why? Mimes make things visible that are invisible, and they do things with their bodies that are impossible. This, along with the classic blank-faced mask-like mime makeup adds up to my theory: that people hate mimes because of a version of the Uncanny Valley. It’s just like having a fear of realistic robots or animated mannequins. Same reason people are uncomfortable around mimes. It’s a pet theory of mine, and I’m sticking to it. What do you think?”

I have been nerding out and talking through some fascinating concepts related to this fear of mimes, what mimes are, and what their role is in the wider world of the Clown. And so I want to share all of what I’ve found with you, by showing a few concrete examples first, so you can vividly see what I’m talking about when I talk about mimes, before I go into a bit of theory. Ready?

Do I need to give you a content warning? Nahh, you’ll be fine. Trust me.

Example: Javier Botet

I won’t post it, but go look for Botet’s movement test video clips (found easily on YouTube) for his horror-flick role of Mama. It’s brilliant. It’s marvelous. … It’s also deeply unsettling. Why? Because his limbs don’t seem to connect correctly, and his joints look like they’re bending wrongly. Ever heard of Slenderman? Yeah that’s him (no seriously—he played Slenderman in the film). Impossibly gangly, Botet knows how to use that body of his to excellent (horrific) effect.

It’s not just how Botet looks or the odd lanky grace with which he moves, either. He’s what we call a great physical actor, too, meaning: he knows how to evoke strong emotion using his body, instead of spoken lines. He expresses intense emotion in his gestures and even his posture. He can do this incredible body-acting with his facial expressions too, but he’s often cast as monsters that obscure the actor’s face under makeup or prosthetics.

Example: Andy Serkis

Andy Serkis’ body type is pretty much the opposite of Javier Botet’s: he’s a bit shorter than average for a male build, and he’s muscular and stocky withal. But his more compact body moves with amazing fluidity and versatility, and his face can tell a story all on its own. This is why, in the role he’s most known for, Gollum in The Lord of the Rings, he’s got Mocap on his face and body, instead of obscured with prosthetics. So you can see that he’s doing all that dark clowning physically, himself.

Creating reality using only physicality is the center of what mime type clowning is all about: this is why I taught movement students this way in the Clownlympics assignment. I restricted their access to props and sets, because I wanted them to get a taste of what it takes to create something from nothing using gesture, posture, and movement only. It’s easy, in realistic modern theatre, to rely on designers’ work to simulate reality around you as an actor. In clowning, it’s all up to the actor to create the world.

This is absolutely how Gollum was made: it was all in Serkis’ physical portrayal. You could argue that this wasn’t a mime performance, as he was a speaking character,* but any discussion of physical virtuosity and uncanny character creation using high level movement skill and incredible facial expression would be incomplete without mentioning Serkis’ Gollum.

*More on the silence of mimes in a moment.

Example: Jerzy Grotowski

Grotowski was an experimental theatre artist who specialized in training his actors in precision movement; his stable of performers underwent incredible discipline in training, and, like my Clownlympics kids but far more intensive, his style of playmaking was very sparse with props and sets. Any design elements he kept to a bare minimum, choosing instead to create each theatrical world with the actors’ movements alone.

This artistic concept Grotowski called: The Poor Theatre. His choice of shows tended toward the shamanic, immersive (before that was a thing), almost ritual style theatre, pared down to actors’ bodies and their virtuosic physicality only. This was sacred clowning, to a T—his work influenced later ritual-heavy theatre groups like La Mama and Living Theatre, all of whom toed the clown-shaman line between theatre and shamanic experience just like Grotowski did.

What’s Yours is Mime

Mime arts were huge in the US in the 1970s, and I’d have to do another whole historical and social-science research sesh to figure out why that might have been. But it was indeed super popular, connected to the burgeoning romanticized tramp life of the RenFaire circuits and the explosion of buskers and other types of street theatre. The mime trend shows up in the stage shows of the ‘70s too—for an example that I’ve talked about before, look at the way the Leading Player’s minion clowns dance in Pippin.

I mentioned Pippin as a shamanic clown musical in my Shaman article, and this huge trend of mime troupes and clowning in the ‘70s certainly had a lot (of “magic”) to do with how Pippin was originally staged in ‘81. Bob Fosse’s choreography for this show was very him, but at the same time very mime-like, too. Especially the splayed jazz hands in opening number “Magic to Do,” and also to some extent in the tiny precision movements in “Glory.” Other numbers, too, include acrobatics and mime-like contact improv type tumbling and stage pictures.

The Broadway revival of Pippin actually takes place in a circus, and is made into a show-within-a-show sort of thing. Reviewers thought, however, that doing that was too on the nose, and the circus spectacle took away from the more intimate, grungy, eerie mime troupe feel of the original.

MasterMime: Marcel Marceau

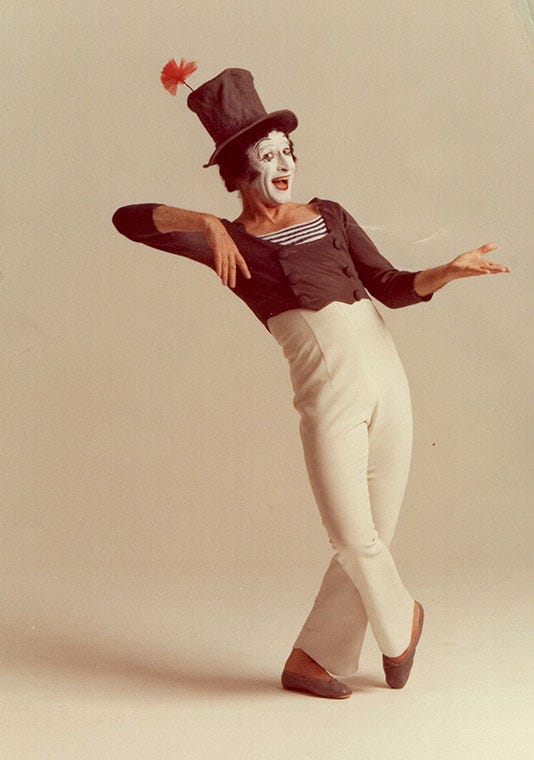

When you think of a mime, the image that pops into your head is no doubt this:

That’s Marcel Marceau’s clown character, Bip. He’s the first modern mime as we know them and the model for all others after him, including costume, makeup, and performance style.

Isolation is key to all mime technique—you can see it in Marceau’s “Mask Maker” act in particular, though of course he’s a master of mime movement in all his work. His work represents the epitome (epitomime?) of creating reality out of thin air—when he mimes an invisible object from nowhere, suddenly you can see it, almost feel its weight, understand its nonexistent mass, until Marceau chooses to put it back into the nowhere from which he conjured it.

Mimesis

Mimesis = imitation of reality (in art), or mimicry of other organisms (in biology/zoology). The term “mime” is a term from early Roman bawdy performances (later in English called pantomime), literally meaning this. Mimesis, mime, mimicry, it’s all the same idea. Mime differs from your basic physical comedy or clowning in its focus on this imitation of reality. Of course, the most obvious thing that distinguishes panto/mime from other types of physical comedy is that it’s silent.

I incorporated this aspect in the Clownlympics assignment requirements for my class: only one set block allowed, no props allowed except your clown hat. Being vocal is okay, but verbal (including sign language or code), not. Old mime was totally silent, sometimes with musical accompaniment.

Above: This phenomenal mime bit illustrates the concept of mimesis (and silent mime style comedy) brilliantly. Note the “rule of three” punchline move that Harpo pulls at the end which serves as a supremely satisfying climax to the tension of the mirror play.

You Are Here

So now we’re getting to the big question: Why do so many of us hate or fear mimes in particular? Is it…? Can it be?

Do mimes make us uncomfortable because they transgress a deep truth about humans and mimicry? Let’s think about this:

Mimicry is how humans learn.

Not only that: Mimicry is how everyone does everything, all the time.

Imitation is the only way we humans are functionally social. We mimic, or imitate, everything around us, in order to be a functioning human. This goes beyond the mimicry a child will practice in order to learn how to human; we continue this mimicry constantly as adults, too. I love to blow businessmen’s minds in my movement seminars by pointing out how they echo a person’s posture or gesture that they’re talking to—most don’t know they’re doing it. This is a very good thing to be aware of, too, if you’re in the business of fundraising or of sales: a fellow human will trust you far more if you mimic the way they’re sitting, or gesturing as they talk, or mirror their facial expression. Of course, if you do it mockingly or if they notice your mimicry, it’ll be thought of as extremely rude, personally insulting even.

A mime’s art is about mimicking reality. But they’re doing it out in the open. When a mime holds, as t’were, the mirror up to Nature,** he’s breaking a deeply ingrained social rule. Mimes say the quiet part out loud (!) by exposing what we all are. Monkey see, monkey do, but Mime mimics. Mocking us to our very face. Fuck that guy. No, but seriously:

Why so serious(ly creepy)?

My theory has a sort of two-pronged concept of the mime’s mimesis being the thing that creeps us out. Both angles have to do with the mime’s practice of mimicking reality, or creating something from nothing (which is how they’re able to do such a thing).

The first prong of the creep-out has to do with the Uncanny Valley. Also the Replicant factor, or body snatchers, or The Thing. Autons from Doctor Who. That creature that’s human seeming, but not quite human. There’s a horror hidden underneath. And when we watch the mime’s white-painted blank mask of a face morph into a mockery of our deepest seeded behavior, it’s a little sickening. Is our newfound AI fear related to the uncanny fear of the mime? Seems like the deep fear of AI’s potential danger is related to: what can it and what will it mimic?

A mime is also a shapeshifter—he’s creating reality from thin air, his blankly painted face not quite familiarly human, and how does he bend his body that way? I call him “him,” but he’s genderless, almost agender in his appearance and movements. Mimes make things seem real that aren’t, and it’s uncanny and weirdly magical. Their bodies are not quite right: indigenous s**nw***ers in particular are monsters that have angles here and there that aren’t quite human, but are so close that our lizard brain gets freaked out. Fear of them is a similar fear of the mime.

It’s the miming of the mime that’s the center of our fear of him—he mimics our subconscious, and it’s profoundly uncomfortable. He imitates reality, and it’s uncannily disturbing. But it takes a vast amount of training to be able to do this at all, let alone to do it well. Is it possible, then, to appreciate the mime’s artifice, the way we do stage magicians? We don’t hate them, do we? (Uh oh, do we? Is this another article?)

Can I leave you with the echo of dropping a reference to the horror of H.P. Lovecraft? His non-Euclidean geometry instills that uncanny horror in a similar way that mimes do. Here, it’s of the body, not of a mysterious room or cave housing an Elder horror, but. You see where I could go with this.

A Mime is a Terrible Thing to Waste

As we learned in my last clowning article about the Fool, the court jester is an essential part of a civilized society, because of his ability (indeed, his sacred duty) to speak truth to power, to remind us of the ridiculousness of society and authority. In my overview of the Shaman, I reminded us of what the Shaman-clown repeats: Eat, Drink, and be Merry; for Tomorrow we Die. That’s why those guys are spooky; they constantly remind us of our flaws and of our mortal coil. At least they also lead us to laugh about it.

Mimes do a similar thing as both of their above clownish siblings: they blow bubbles into a cupful of the void, then hold a mirror up to our own nature. That’s a powerful art, isn’t it? One to be appreciated, not hated.

ENCORE: I just had to include this bit below. Is it mime, or is it clowning? Yes. One small content warning, about this one: it’s…bloody. Stupid, silly bloody, but still. Skip it if you’re not in the mood.

FUN FACT about the arts of silent mime: in Mel Brooks’ madcap silent movie comedy (I think it’s just called Silent Movie), only one word was spoken aloud during the whole thing. That word was, “No!” Who spoke it? Marcel Marceau.

**You didn’t think I’d go a whole article without referencing classic literature, did you? O ye of little faith. (Oops there I go again…)

CLOSING NOTE: There is one particular branch of clowning type performance that is from an inarguably ugly tradition, in the US and across Europe, though the American flavored article is likely the one you’ve heard of. It’s a vaudeville subgenre called Minstrelsy. This wildly popular form of slapstick clowning included a white-face painted clown who acted as a ringmaster, an elegant straight man, to the bumbling bumpkin clown character, who was Black. Usually, the latter character was a white actor in blackface, though it wasn’t unheard of to have an actual Black performer playing that role. Minstrelsy … was very racist. It was one of those popular cabaret acts, like the “Chop Suey circuit” that played exaggeratedly on gross racist ideology. This is why I haven’t covered Minstrelsy in my clowning articles: I’m not the one to write about this form of clowning—I do not need to put my white voice onto this ugly practice. Just know that it was a thing. If you’re curious and would like to do some research, please try and find some BIPOC historians to learn from about it.

Thanks for this. This is a great piece.

And you're right, Botet in Mama is terrifying. when I was watching the piece, it recalled the music of the movie version fo Silent Hill.

As for immitation being the basis of human behavior, particularly the example of the business person,I have even more to add. This fundamental truth is part of the basis of in-group/out-group behavior, or in the ethical realm, moral communities. That is, the term "moral community" describes an individual's or groups sense and intutions of moral responsibility. SO, for instance, racism and sexism are in part trigger conditions for being "pushed away" or "pushed out" of the moral community. I'm bringing this up because most people don't realize how crucial mimicry is as a moral foundation; if people "aren't like us" even at the level of how we move or hold bodily tension, it quickly becomes the basis for subtle distance and possibly exclusion. A person can just pay attention to the bodies of working vs. professional class persons.

This topic sparks my interest given my multicultural background and having to navigate these issues since I was a child, and always having to decide who or what I'd imitate, which is something most (monocultural) Americans don't face.

The definitive pronouncement of Google's Gemini is that Meher Baba, the spiritual master who eschewed oral communication for almost 44 years cannot properly be described as mimetic.

(Lest I be misunderstood, this is not a counter-claim to anything in your article: more of a "stub" as Wikipedia would say: a tickle that needed expression in its own right, lest the thought were to flow away on the wash of my forgetting, and this wasn't the worst place to pin a comment.)

(Indeed, writing a comment has the lasting effect of a college freshman writing a poem on a fresh sheet of paper. )