Commedia

You thought I had no more Vocab Words about clowning? O what fools these mortals be…

So much interesting history surrounding clowning arts, readers. There’s a lot. And if you think you hate all of it, methinks you’ll change your mind after learning about today’s Clown Flavor of the Week. Because, I’ll bet you actually enjoy this type of clowning on a regular basis, even if you don’t know it yet. What am I talking about? Buckle up, buttercups, and travel with me all the way down to 17th century Italy…

Commedia dell’arte

This theatrical art form was wildly popular across Europe in the time periods basically from around 1600 through the 1700s (though, as you’ll see, it kind of never stopped). It sort of originated in Italy, loosely based in the old raunchy Roman pantomime tradition, but it evolved and spread and blossomed into a total Western theatre phenomenon, that I argue we’re all still actively practicing today, particularly since 2000 and the advent of Reality TV as a popular genre. But I’ll get into that later. Suffice to say that commedia dell’arte was a type of comedic theatre, was a thing, and was an explosion of popular culture. There’s a whole thing about it really having a clandestine boom during Cromwell’s crackdown on all things theatre, and its bursting out of that again after, but ehhhh just go read a history book about that. But. Point is. It was big. Big.

There are a few things that distinguish commedia dell’arte (from now on I’m just gonna call it commedia, without the italics, ‘K?) from other forms of comedic theatre. First, these plays weren’t plays at all—the shows were all improvised, non-scripted, and unplanned. Second, commedia stories included slapstick* clown conflicts, funny farcical situations, and physical comedy that was extreme to the point of actual acrobatics. Most characters wore half or full masks, and their outfits were exaggerated, colorful, and stylized specifically to each character. Storylines would usually revolve around the wacky shenanigans surrounding two young lovers who are trying to get together but are thwarted by stingy dads, cowardly rivals, scheming servants, dumbass messengers, and the like. Which brings me to the next distinguishing characteristic of commedia:

Stock Characters

This is the main detail that sets commedia apart from other forms of theatre of this time (even unscripted performance arts): the stock characters. Stock characters means that the characters are an archetype or a generalization as opposed to a realistically detailed human. What this does is make it easier for the actors to react believably to various improvised circumstances. It’s also a comfort thing for an audience. Just like we do today when we pour ourselves a cold one and settle in to Season 257 of Survivor, an audience of commedia knows exactly what they’re in for when suddenly Pantalone hobbles out onto the stage with Il Dottore in tow.

And actually, there’s literally no difference. I’ll talk about this in a second. But first, let’s look at who each of these stock characters are. Hint: if any of these characters sound familiar to you, even if you’ve never heard of commedia before, you’re not wrong.

Pantalone

Named after the wrinkly pantaloons that are his costume trademark, Pantalone is the parsimonious patriarch of the commedia posse. Elderly, doddering, rich, miserly, mean, and fully selfish, Pantalone is the asshole boss, the tyrannical father, the tight-fisted abusive old husband, whose grasping ways make everyone’s life hell. But he’s also dim as a sack of hammers, and so any clever character, if they watch their step and choose their words carefully, can absolutely get what they want out of him.

Innamorata

This word simply means ‘lovers,’ and that’s exactly what these characters are. They’re named all kinds of different things depending on the commedia company, and as such, aren’t named as precisely for their roles as other stock characters are. These two would also often be the only ones onstage in a commedia show that went unmasked. My theory on why this is is that since they’re supposed to be young, innocent, not that crafty, and only about pure love, their fresh faces can be exposed. I dunno—what do you think of that poetic concept? I think it’s sound.

Anyway, you get the idea: a usual improvised plot of a commedia show could be: Oh dear, the innamorata are in love! But the girl’s miserly uncle (Pantalone) wants to marry her off to someone old, ugly, and rich (like Punchinello below). The boy innamorato is too young, nameless, and poor to be a worthwhile suitor. But they’re in loovvvvve! Whatever will they do? Quick, call on Girl Innamorata’s waiting maid! She’ll help sneak messages back and forth. And maybe she’ll get the help of her clever servant husband. Speaking of her:

Colombina

Coming fresh from centuries-old traditions across Europe of No Women Allowed onstage, Colombina sashays her sassy self into the new rules of commedia, bumping her hips. Unabashedly female, her painted lips and pushed up cleavage show that this is a new age of comedy. Colombina is not your fresh innocent lamb, huh-uh: she’s lower class and lower morals, often in the role of servant in Pantalone’s household, or very rarely his loose wife, running around town behind his back or even lording it in his face. More often, though, this saucy wench is connected to our next clever servant character in the roster:

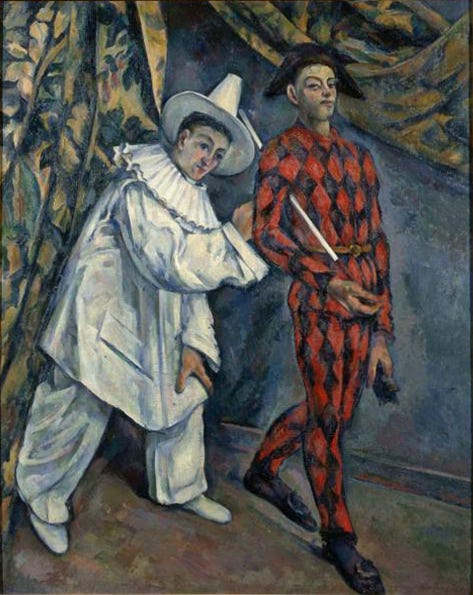

Arlecchino

More popularly known today by his French name, Harlequin, he’s the ultimate smartass servant who schemes and steals and has his clever fingers in every single plot pie possible. He’s your classic court jester type character, who’s the smartest guy in the room but also only the servant and messenger who must bow to Pantalone, who’s usually his boss. Often, Colombina is Harlequin’s partner in crime, also his wife or girlfriend, the sassy servant wench whose wit matches his own and who joins in his shenanigans. *The term ‘slapstick’ comes from one of the many tools in Harlequin’s arsenal, a hinged slat of wood that makes a loud CLACK sound when it hits an object (like a buttock). Also, another fun fact: Arlecchino’s famous multicolored outfit is an evolution directly inherited from court jesters.

Punchinello

The thing I find most interesting about this stock character is his survival in the same costume and mask, in puppet form in English ‘Punch & Judy’ vignettes. But his type is easily recognizable, with his big red nose from all the drinking, and the paunch that proceeds him. Punchinello is all about food and sex, and his greasy mug is just as nasty as the passes he makes at anything vaguely female that comes across his path. Often he appeared onstage with a chicken leg or a beer mug in his fist, and a stuffed codpiece that would lead the way as he walked. Gluttony and lechery is the Punchinello way, and woe betide the passers-by that encounter him in conflict with Il Capitano. Fortunate for commedia audiences, though. Rapier vs. tankard? That’s a fun spectacle (and in fact I’ve choreographed one of those before, for a RenFaire bit).

Il Dottore & Il Capitano

These two are named after their professions, and you know them well. Our friend the Dottore is the Doctor, a quack that uses big words that he doesn’t understand (or lots of fake Latin), and charges a hefty fee for his fully ineffective remedies. Usually, Pantalone is a hypochondriac, being an older guy, and he keeps Il Dottore around him all the time to furnish him with the medicine he thinks he needs, and the fawning attention he definitely does. Capitano is The Captain who blusters and brags about his prowess both on the battlefield and in the bedroom. But when he is faced with a real live woman, or an actual threat of a duel, he slinks away in fear, making all the excuses he can for his cowardice.

Pierrot

Though you may remember his Italian namesake from opera: Pagliacci, this moony character as we know him best is known by the French version of his name. Pierrot is the white-face-painted, baggy white smocked, black capped melancholic who strums his lute and composes sad lyrics of love that’s always unrequited. My pet theory is that Pierrot is one of the main aesthetic influences of contemporary Goth fashion and culture, with his white face, black eyeliner, and enduring poetic sadness.

Zanni

This is a collective term for the largely mute population of extras that would enact scenes of non-speaking physical comedy as background business or as interludes between acts or scenes between the main characters. These are closest to what we would later see in modern circus clowning, and even today in shows like Cirque du Soleil, where the center of the funny and the delight is in extreme physical gags. Buster Keaton, though a main character in his films, is a prime later example of what kinds of nonsense the commedia zanni would get up to.

Now, an actual commedia show would be fully improvised, as I said above, but playwrights even within the heyday of its popularity would incorporate these stock characters into their scripted plays, too. Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s farces do this pretty overtly, and Moliere himself famously said outright that his comedies were absolutely commedia pieces put to script. And I’m sure that, after having read this list of stock character descriptions, you recognize these characters, under different names, in entertainment today, scripted or no.

I mentioned Survivor in the intro to this historical account, but I wasn’t actually doing so lightly: the way that the casts of reality shows like that get put together is literally this: creating a group of stock characters and letting them do what they do. It creates conflict immediately and effortlessly, no script needed.

Here’s a fun assignment that I always give to my theatre students: Do a scavenger hunt and find these stock characters in any of your current entertainment. The above motley crew is still out there, getting into the same mischief they have been for centuries past, and no doubt, centuries to come.

Oh, where did I get all this vasty knowledge about commedia dell’arte? I realize I didn’t cite any of it. Welp, that’s because all this history is in my brain, lovely readers. I’ve been studying and practitioning (is that a word? It is now) theatre and in particular, clowning, for so long and with such intensity that I couldn’t tell you what specific sources I might cite for any of this. It’s my own historical overview from my own noggin. Feel free to verify and fact-check me, though, all you like. And actually, commedia is a pretty fun rabbit hole to fall down, if you choose to do so.