AUTHOR’S NOTE: I wrote a much briefer, less involved and less interesting version of this piece on a pen-named blog in 2019, just after my trip to NYC. I have expanded and pontificated and updated it since then. I keep wanting to return to the Big Apple, but between the Plague and the dire state of my bank account, I haven’t yet been able to. Hopefully one day soonish.

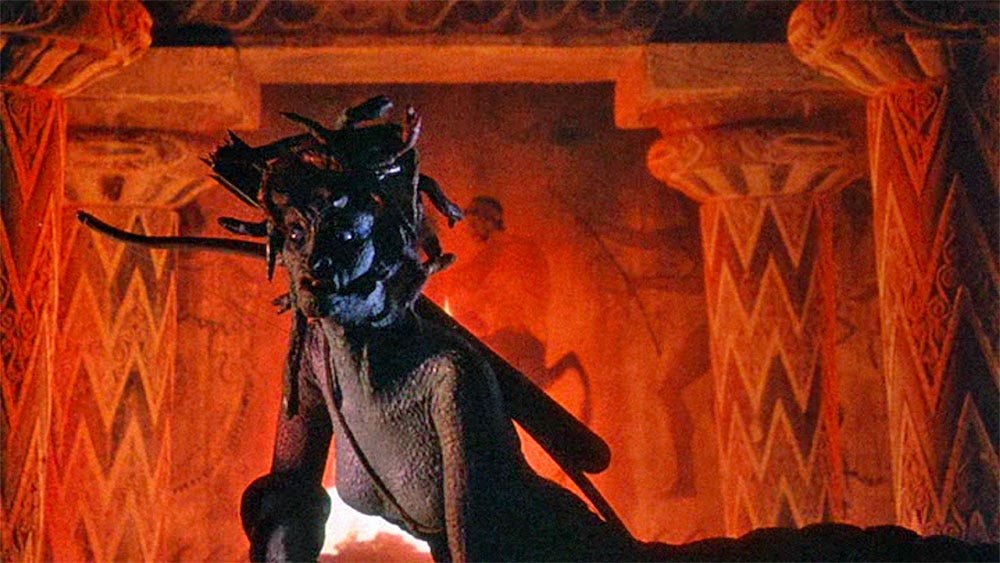

One of the coolest things I saw at The Met during my first ever visit to NYC was also one of the first objects I saw, in the first room I entered. It was a vase (like an amphora? An urn? Kylix? Kantharos? I don’t know what type it is), depicting Perseus’ decapitation of Medusa, and Pegasus emerging from the wound.

I mean, this is one of the most well-known stories of all time. It’s been told and retold countless times; and even though you may not know the actual story of Perseus and Medusa, or the weird way Pegasus was born, you definitely know what a Pegasus is. You most likely also know very well that Medusa has snakes for hair and that her gaze’ll turn you to stone. There’s even a strong likelihood that you know (even if you didn’t remember the hero’s name) that Perseus cut her head off by using his mirrored shield so he wouldn’t have to look directly at her, and that after her defeat he wielded her severed head as quite the effective weapon.

I get so excited about stuff like this. It’s an example of how astonishing it is to look down a time tunnel that extends for so long: this vessel has that story depicted on it, clear as clay. And it’s, like, two thousand years old. And yet I can look at it and go, Oh yeah: that story. I know that story.

I have been a scholar of what I call by the collective noun Old Story for a very very long time. Most of my remembered life, in fact. In my teen years I discovered Joseph Campbell’s studies that came before mine, and his powerful works of synthesis (revolutionary for his time) excited me very much. Still does, actually, especially because I myself have expanded it beyond heterosexual masculinity in a way that honors his work, maintains scholastic rigor, while still recognizing which bits might ring problematic in our time period of inclusion. I’ve actually constructed a few variations on the Monomyth/Hero’s Journey, as well as blended it together with the acting training of the 3 Rules (really, it’s 3 questions) to make a useful tool for story creation. But I won’t go into more details here—I’ve written extensively about this a few times before, so look there for any Journey into the Monomyth you’re in the mood for:

There are many reasons why I’m excited about Campbell’s Monomyth, and why it makes plenty of people uncomfortable. But it comes back to the way I always describe it, particularly to my writing students: we’re all skeletons underneath. Strip me of my clothes and flesh and blood, and do the same to the most different-looking person to me, and then stand our skeletons next to each other. Odds are you won’t see much of a difference, if any. Maybe one of us is taller, or if you know how to look at bones, you’ll notice our sex is different, maybe. But really the differences are tiny. Put our flesh and our hair and our clothing back on, and that’s where we’ll begin to show our differences. The base, though, the skeleton? Pretty much the same.

That’s what makes those old stories so potent, and (I would aver) is why we keep telling them, over and over. The Old Story is our base, our skeleton; it’s what keeps us standing upright. For example: Did you know that there’s a version of Cinderella in nearly every culture on earth? The put-upon daughter or stepdaughter, abused by older step/sisters and /mother, finds magical help (sometimes the magic from a dead mother’s grave, sometimes a fairy godmother, or even a magical fish or falcon) to attend a noble or royal man’s party. There are magic dresses, mistaken identity, and a dropped shoe by which the nobleman finds his love again. Sometimes the shoe is glass. Sometimes it’s luxurious fur, or rose-gold. And we haven’t stopped telling that story.

Perseus and Medusa isn’t nearly as pervasive a story as Cinderella, you say? So tell me: which of the My Little Ponies have wings? What was the main conflict in the second Harry Potter book? And isn’t there another YA series featuring Percy (short for Perseus?) and a bunch of Greek Gods?

The Greek gods are like the ultimate reality show or soap opera whose interconnected drama never ends. And why should it? It’s what keeps us going. It’s in our bones.